I Think You'll Find It's a Bit More Complicated Than That (37 page)

Read I Think You'll Find It's a Bit More Complicated Than That Online

Authors: Ben Goldacre

To be clear, I’m always conflicted over this kind of psychology research. On my left shoulder there is an angel. She says it’s risky to extrapolate from rarefied laboratory conditions to the real world. She says that publication bias in this field is extensive, so whenever researchers get negative findings, they’re probably left unpublished in a desk drawer. And she says it’s uncommon to see a genuinely systematic review of the literature on these topics, so you rarely get to see all the conflicting research in one place. My angel has read the books of

Malcolm Gladwell

, and she finds them to be silly and overstated.

On my right shoulder, there is a devil: she thinks this stuff is

cool and fun.

She is typing right now.

The researchers did four miniature experiments. In the first, they took twenty-eight students, over 80 per cent of whom said they believed in good luck, and randomly assigned them to either a superstition activator or a control condition. Then they put them on a putting green. To activate a superstition, for half of them, when handing over the ball the experimenter said: ‘Here is your ball. So far it has turned out to be a lucky ball.’ For the other half, the experimenter just said, ‘This is the ball everyone has used so far.’ Each participant then had ten goes at trying to get the ball into the hole from a distance of 100 cm: and lo, the students playing with a ‘lucky ball’ did significantly better than the others, with a mean score of 6.42, against 4.75 for the others.

Then they moved on to a second experiment. Fifty-one students were asked to perform a motor-dexterity task: an irritating, fiddly game where they had to get thirty-six little balls into thirty-six little holes by tilting a Perspex box. Beforehand, they were randomly assigned to one of three groups, each of which heard a different phrase just before starting. The superstition activator was ‘I press the thumbs for you,’ a German equivalent of the English expression ‘I’ve got my fingers crossed.’ The two ‘control’ or comparison groups were interesting. One group were told ‘I press the watch for you,’ with the idea that this implied a similar level of encouragement (I’m not so sure about that), and the other were told, ‘On “go”, you go.’ As predicted, the participants who were told someone was keeping their fingers crossed for them finished the task significantly faster.

Then things got more interesting, as the researchers tried to unpick why this was happening. They took forty-one students who had a lucky charm, and asked them to bring it to the session. It was either kept in the room, or taken out to be ‘photographed’. Then they were told about the memory task they were due to perform, and asked a whole bunch of questions about how confident they felt. The ones with their lucky charm in the room performed better on the memory game than those without; but more than that, they reported higher levels of ‘self-efficacy’, which was correlated with performance.

Finally, they probed these mechanisms even further. Thirty-one students were asked to bring their lucky charm. It was either taken away or not, and they were given an anagram task. Before starting, they were asked to set a goal: what percentage of all the hidden words did they think they could find? Then they began. As expected, participants who had their lucky charm in the room performed better, and reported a higher degree of ‘self-efficacy’ as before. But more than that, people who had their lucky charm in the room set higher goals, and also persisted longer in working on the task.

So there you go. Almost everyone has some kind of superstition (mine is that I should mention I noticed this study through my friends

Vaughan Bell

and

Ed Yong

on Twitter). What’s interesting is that superstition works, because it improves confidence, lets you set higher goals, and encourages you to work harder. In a lab. In one experiment. In a field riven with publication bias. You now know everything you need to decide if this applies to your life.

Guardian

, 1 May 2010

Elections are a time for smearing. But do smears work, and if so, what’s the best way to combat them?

A new experiment

published this month in the journal

Political Behavior

tries to examine the impact of corrections. The findings are disturbing: far from changing people’s minds, if you are deeply entrenched in your views, a correction will only reinforce them.

The first experiment used articles claiming that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction immediately before the US invasion. One hundred and thirty participants were asked to read a mock news article, attributed to Associated Press, reporting on a Bush campaign stop in Pennsylvania during October 2004. The article describes Bush’s appearance as ‘a rousing, no-retreat defense of the Iraq war’, and gives genuine Bush quotes about WMD: ‘There was a risk, a real risk, that Saddam Hussein would pass weapons or materials or information to terrorist networks, and in the world after September the 11th … that was a risk we could not afford to take.’ And so on.

The 130 participants were then randomly assigned to one of two conditions. For half of them, the article stopped there. For the other half, the article continues, and includes a correction: it discusses the release of the Duelfer Report, which documented the lack of Iraqi WMD stockpiles – and the lack of an active production programme – immediately prior to the US invasion.

After reading the article, subjects were asked to state whether they agreed with the following statement: ‘Immediately before the US invasion, Iraq had an active weapons-of-mass-destruction program, the ability to produce these weapons, and large stockpiles of WMD, but Saddam Hussein was able to hide or destroy these weapons right before US forces arrived.’ Their responses were measured on a five-point scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’.

As you would expect, those who self-identified as conservatives were more likely to agree with the statement. Separately, meanwhile, more knowledgeable participants (independently of political persuasion) were less likely to agree. But then the researchers looked at the effect of whether you were also given the correct information at the end of the article, and this is where things get interesting. They had expected that the correction would be less effective for more conservative participants, and this was true, up to a point. For very liberal participants the correction worked as expected, making them more likely to disagree with the statement that Iraq had WMD, when compared with those who were also very liberal but who received no correction. For those who described themselves as left of centre or centrist, the correction had no effect either way.

But for people who placed themselves ideologically to the right of centre, the correction wasn’t just ineffective, it actively backfired: conservatives who received a correction telling them that Iraq did not have WMD were

more

likely to believe that Iraq had WMD, when compared with those who were given no correction at all. You might have expected people simply to dismiss a correction that was incongruous with their pre-existing view, or to regard it as having no credibility: in fact, it seems such information actively reinforced their false beliefs.

Maybe the cognitive effort of mounting a defence against the incongruous new facts entrenches you even further. Maybe you feel marginalised and motivated to dig in your heels. Who knows? But these experiments were then repeated, in various permutations, on the issue of tax cuts (or rather, the idea that tax cuts had increased national productivity so much that tax revenue increased overall) and stem-cell research. All the studies found exactly the same thing: if the original dodgy fact fits with your prejudices, a correction only reinforces these even more. If your goal is to move opinion, this depressing finding suggests that smears work; and what’s more, corrections don’t challenge them much, because for people who already disagree with you, it only make them disagree even more.

Guardian

, 12 March 2011

This week our

government committed itself

to the removal, albeit slowly, of cigarette displays in shops. But plain packaging on cigarettes has been delayed for further consultation.

The Unite union is unimpressed. It represents 6,000 people in tobacco production and distribution, and

put out a statement

: ‘Switching to plain packaging will make it easier to sell illicit and unregulated products, especially to young people’. This ‘may increase long-term health problems’. Tory MP Philip Davies said: ‘Plain packaging for cigarettes would be gesture politics … it would have no basis in evidence.’

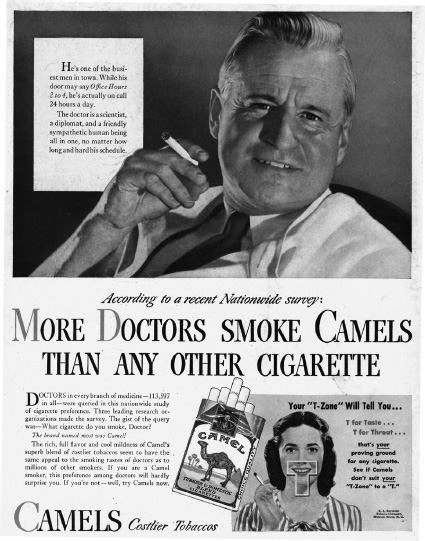

Everyone is entitled to their own opinions, but not their own facts. Cigarette packaging has been used for brand building and sales expansion, and that is bad enough; but it has also been used for many decades to sell the crucial lie that cigarettes which are ‘light’, ‘mild’, ‘silver’ and the rest are somehow ‘safer’.

This is one of the most important con tricks of all time, because people base real-world decisions on it, even though we have known for several decades that low-tar cigarettes are no safer than normal cigarettes. Manufacturers’ gimmicks, like the holes on the filter by your fingers, confuse laboratory smoking machines, but not people. Smokers who switch to

lower-tar brands compensate

with larger, faster, deeper inhalations, and by smoking more cigarettes. The collected data

from a million people

shows that those who smoke low-tar and ‘ultra-light’ cigarettes get lung cancer at the same rate as people who smoke ‘normal’ cigarettes. They are also, paradoxically,

less likely to give up

smoking.

So the ‘light’, ‘pale’ and ‘mild’ packaging sells a lie. But do people know this? In data from two

population-based surveys

, a third of smokers believed incorrectly that ‘light’ cigarettes reduce health risks, and were less addictive (it’s

71 per cent in China

). A random

telephone digit survey

of 2,120 smokers found they believed, on average, that ‘ultra lights’ convey a 33 per cent reduction in risk. A postal survey of

five hundred smokers

found a quarter believed ‘light’ cigarettes are safer. A school-based questionnaire of

267 adolescents

found, once again, as you’d expect, that they incorrectly believed ‘light’ cigarettes to be healthier and less addictive.

Where do all these incorrect beliefs come from?

Careful manipulation

by the tobacco companies, as you can see for yourself, in their internal documents available for free online. They aimed to

deter quitters

, and ‘mild’ products – which were made to seem safer and less addictive – were the

perfect vehicle

.

But over fifty countries, including the UK, have now banned a few magic words like ‘light’ and ‘mild’. So is that enough? No. A survey of 15,000 people

in four countries

found that after the ban there was a brief dip in false beliefs in the UK, but by 2005 we bounced back to having the same false beliefs about ‘safer-looking’ brands as the US.

This is because brand packaging continues to peddle these lies. A

street-interception survey

from 2009 of three hundred smokers and three hundred non-smokers found that people think packages with ‘smooth’ and ‘silver’ in the names are safer, and that cigarettes in packaging with lighter colours, and a picture of a filter, were also safer.

Of course

tobacco companies know this

. As Philip Morris said in its internal document ‘

Marketing New Products

in a Restrictive Environment’: ‘Lower delivery products tend to be featured in blue packs. Indeed, as one moves down the delivery sector, then the closer to white a pack tends to become. This is because white is generally held to convey a clean healthy association.’

If you’re in doubt about the impact this branding can have,

‘brand imagery’ studies

show that when participants smoke the exact same cigarettes presented in lighter-coloured packs, or in packs with ‘mild’ in the name, they rate the smoke as lighter and less harsh, simply through the power of suggestion. These illusory perceptions of mildness, of course, further reinforce the false belief that the cigarettes are healthier.

But these aren’t the only reasons why banning a few words from packaging isn’t enough. A study on

six hundred adolescents

, for example, found that plain packages increase the noticeability, recall and credibility of warning labels.

There’s no real doubt that the extended, complex, interlocking branding and packaging machinations of cigarette companies play a major role in misleading smokers about the risks. They downplay the harms of smoking, one of the biggest killers in the world, and sadly nothing from Unite – for shame – or some Tory MP will change that.

If you don’t care about this evidence, or you think jobs are more important than people killed by cigarettes, or you think libertarian principles are more important than both, then that’s a different matter. But if you say the evidence doesn’t show evidence of harm from branded packaging, you are simply wrong.