I Think You'll Find It's a Bit More Complicated Than That (41 page)

Read I Think You'll Find It's a Bit More Complicated Than That Online

Authors: Ben Goldacre

One doesn’t know whether to laugh or cry at the

Guardian

’s eagerness to wash its dirty linen in public. It is undeniably magnificent, but – in my view – no way to run a newspaper. I wonder at the psychiatrist’s bills. What does it tell us about health and science reporting? First, most disinterested observers think standards are pretty high (a report by the Department of Business last January said it was in ‘rude health’). Second, reporters are messengers – their job is to tell, as accurately as they can, what has been said, with the benefit of such insight as their experience allows them to bring, not to second guess whether what is said is right. But third, reporters are also under pressure. Newspaper sales are declining, staff have been cut, demands are increasing.

Goldacre is right to highlight the fact that there is too much ‘churnalism’ – reporters turning out copy direct from press conferences and releases, without checking, to feed the insatiable news machine. This ought to be stopped. But no one, so far, has come up with a commercially realistic idea of how to stop it.

In the meantime, while raging rightly at the scientific illiteracy of the media, he might reflect when naming young, eager reporters starting out on their careers that most don’t enjoy, as he does, the luxury of time, bloggers willing and able to do his spadework for him (one pointed out the flaws in Campbell’s report on the

Guardian

website five days before Goldacre’s column appeared) and membership of a profession (medicine) with guaranteed job security, a comfortable salary and gold-plated pension. If only.

Make of that what you will. Jeremy Laurance mentioned that this is the second time I’ve written about a piece by Denis Campbell. Below is the first, a front-page splash by Denis in the

Observer

.

MMR

: The Scare Stories Are Back

British Medical Journal

, 18 July 2007

It was inevitable that the media would re-ignite the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) autism scare during Andrew Wakefield’s General Medical Council hearing. In the past two weeks, however, a front-page splash in the

Observer

has drawn widespread attention: the newspaper effectively claimed to know the views of named academics better than those academics themselves, and to know the results of research better than the people who did it. Smelling a rat – as one might – for once, I decided to pursue every detail.

The

Observer

’s story made three key points: that new research had found an increase in the prevalence of autism, to one in fifty-eight; that the lead academic on this study was so concerned he suggested raising the finding with public health officials; and that two ‘leading researchers’ on the team believed that the rise was due to the MMR vaccine. By the time the week was out, this story had been recycled in several other national newspapers, and the one in fifty-eight figure had even been faithfully reproduced in a

BMJ

news article.

On every one of these three key points the

Observer

story was simply wrong.

The newspaper claimed that an ‘unpublished’ study from the Autism Research Centre in Cambridge had found a prevalence for autism of one in fifty-eight. I contacted the centre: the study that the

Observer

reported is not finished, and not published. The data have been collected, but they have not been analysed.

Unpublished data is a recurring theme in MMR scares, and it is the antithesis of what science is about: transparency, where anyone can read the methods and results, appraise the study, decide for themselves whether they would draw the same conclusions as the authors, and even replicate, if they wish.

The details of this study illustrate just how important this transparency is. It was specifically designed to look at how different methods of assessing prevalence affected the final figure. One of the results from the early analyses is ‘one in fifty-eight’. The other figures were less dramatic, and similar to current estimates. In fact the

Observer

now admits it knew of these figures, and that these should have been included in the article. It seems it simply cherry-picked the single most extreme number – from an incomplete analysis – and made it a front-page splash story.

And why was that one figure so high anyway? The answer is simple. If you cast your net as widely as possible, and use screening tools, and many other methods of assessment, and combine them all, then inevitably you will find a higher prevalence than if – for example – you simply trawl through local school records and count your cases of autism from there.

This is not advanced epidemiology, impenetrable to journalists – this is basic common sense. It would not mean that there is a rise in autism over time, compared with previous prevalence estimates, but merely that you had found a way of assessing prevalence that gave a higher figure. More than that, of course, when you start doing a large-scale prevalence study, you run into all kinds of interesting new methodological considerations: Is my screening tool suitable for use in a mainstream school environment? How does its positive predictive value change in a different population with a different baseline rate? And so on.

These are fascinating questions, and for that reason statisticians and epidemiologists were invented. As Professor Simon Baron-Cohen, lead author on the study, says: ‘This paper has been sitting around for a year and a half specifically because we’ve brought in a new expert on epidemiology and statistics, who needs to get to grips with this new dataset, and the numbers are changing. If we’d thought the figures were final in 2005, then we’d have submitted the paper then.’

The

Observer

, however, is unrepentant: it has the ‘final report’. And what is this document? I can’t get the paper to show it to me (and what kind of a claim about scientific evidence involves secret data?), but grant-giving agencies expect a report every quarter, right through to the end of the grant, and it seems likely that what the

Observer

has is simply the last of those: ‘That might have been titled “final report”,’ said Professor Baron-Cohen. ‘It just means the funding ended, it’s the final quarterly report to the funders. But the research is still ongoing. We are still analysing.’

But these are just nerdy methodological questions about prevalence (if you skip to the end, there is some quite good swearing). How did the

Observer

manage to crowbar MMR into this story? Firstly, it cranked up the anxiety. According to the newspaper, Baron-Cohen ‘was so concerned by the one in fifty-eight figure that last year he proposed informing public health officials in the county’.

But Professor Baron-Cohen is clear: he did no such thing, and this was simply scaremongering. I put this to the

Observer

, which said it had an email in which Baron-Cohen did as the paper claimed.

Observer

staff gave me the date. I went back to the professor, who went through his emails. We believe that I too now have the email to which the

Observer

refers. It is one sentence long, and it is Professor Baron-Cohen asking if he can share his and the other researchers’ progress with a clinical colleague in the next-door office. This dramatic smoking gun reads: ‘can i share this with ayla and with the committee planning services for AS [autism services] in cambridgeshire if they treat it as strictly confidential?’

Professor Baron-Cohen told me, ‘That’s not saying I’m concerned, or that we should notify anybody; these are just the people who run the local clinic, who I share a corridor with, who said they were interested to hear how it was going so far. They are not public health officials, and it’s not alarmist, it’s not voicing concern, it’s simply saying: “Am I allowed to share a paper with a colleague in the next-door office?” It seems very important to me that we discuss clinical research with clinical colleagues, and I only stressed confidentiality because the paper was not yet final.’

But what about the meat? The

Observer

claims that ‘two of the academics, leaders in their field, privately believe that the surprisingly high figure [one in fifty-eight] may be linked to the use of the controversial MMR vaccine’. This point is repeatedly reiterated, with a couple of other scientists disagreeing so as to create that familiar, unnerving, illusory equipoise of scientific opinion that has fuelled the MMR scare in the media for almost a decade now.

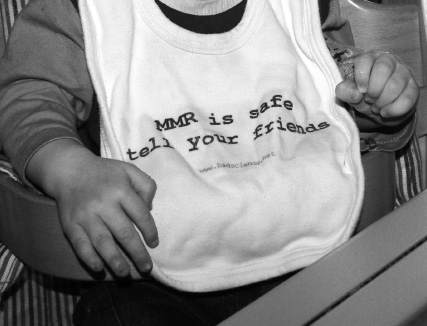

These ridiculous baby bibs are available from

www.badscience.net

, and they are an excellent way to start interesting conversations with other parents. (Nobody ever buys them.)

But in fact the two ‘leading experts’ concerned about MMR were not professors, or fellows, or lecturers: they were research associates. I rang both, and both were very clear that they wouldn’t really describe themselves as leading experts. One is Fiona Scott, a psychologist and very competent researcher at Cambridge. She said to me: ‘I absolutely do not think that the rise in autism is related to MMR.’ And: ‘My own daughter is getting vaccinated with the MMR jab on July 17.’

She also says, astonishingly, that the

Observer

never even spoke to her before incorrectly reporting that she has a privately held view that MMR might be partly to blame for autism. I say ‘reporting’, but in some ways it’s more like an accusation. Dr Scott was horrified. She simply does not believe that MMR has caused a rise in autism.

And yet the

Observer

’s ‘Readers’ Editor’ column one whole week later (15 July), when the paper half-heartedly addressed some (and I mean some) of the criticisms of its piece, reinforced the idea that she holds this view. It’s like a repeating nightmare. They say they know she does, because of a report she wrote, from 2003.

I trudged back to Scott. Firstly, she tells me, this was a legal report pertaining to a specific group of disabled children, submitted four years ago. Secondly, her view has been, and is, that if MMR has a causative role in symptoms which fit into a diagnostic category of autism (which is after all very broad, and can easily subsume a lot of children with learning difficulties and organic injury), then the numbers are so small that they are not in excess of what people already routinely expect in side effects from vaccines: again, she does not think MMR causes a rise in autism prevalence.

But lastly, even if she ever had, in 2003, in one report, made such a suggestion, one is entitled to change one’s view in over four years of working and researching, and in the face of new evidence and experience; and indeed that would be admirable. If you’re saying someone holds a view, right now, and you haven’t even asked them, and they loudly say they don’t, then it doesn’t really matter what you think you’ve read in a court report from half a decade ago: you’re on very shaky territory.

But the paper still has not contacted Fiona Scott: apparently the

Observer

knows the opinions of this woman better than she knows her own mind, despite her public protestations. In fact the only voice Dr Scott could find (while the

Observer

continued to describe her as a ‘dissenter’) was in the online comments underneath the Readers’ Editor piece, where she posted an impassioned and rather desperate message. I shall reproduce it almost in full, because she deserves the space the print

Observer

has repeatedly denied her:

I feel, given that I was one of the two ‘leaders in the field’ (flattering, but rather an exaggeration) reported as linking MMR to the rise in autism, that I should quite clearly and firmly point out that I was never contacted by and had no communication whatsoever with the reporter who wrote the infamous

Observer

article. It is somewhat amazing that my ‘private beliefs’ can be presented without actually asking me what they are. What appeared in the article was a flagrant misrepresentation of my opinions – unsurprising given that they were published without my being spoken to.