I Was Jane Austen's Best Friend (8 page)

Read I Was Jane Austen's Best Friend Online

Authors: Cora Harrison

‘Oh, that’s Tom Chute; I’m madly in love with him.’ She didn’t blush though, so I think it was just a joke.

Wednesday, 9 March 1791

Today was another good day. The weather was fine and sunny, but very frosty. Mr Austen and his students were working hard to make up for the loss to their studies from the day’s hunting, so Jane and I went for a walk by ourselves.

It felt odd to be able to put on our bonnets and cloaks and just stroll out of the front door without saying a word to anyone. Back home, in Bristol, my mother never used to allow me out by myself, not even to a shop a few doors away from our house. She always had to accompany me, and as we had no gentleman in the house we could never go out once it became dark. And of course Augusta was so prim and proper that she didn’t walk out without Edward-John or a servant to accompany her once evening came.

But here at Steventon, in the country, it was different. It was so lovely to be able to pick primroses and watch the birds building their nests. As we went down the laneway towards the church I told Jane how much I admired her house, especially the casement windows. I think they are much nicer than sash windows.

‘It’s a terrible old ruin of a place.’ Jane had to make everything very dramatic. The house could have done with a coat of paint, inside as well as out, but it certainly wasn’t a ruin.

‘Why are we going to church?’ I was surprised at Jane. On Sunday she had begged her mother to allow her to stay at home with me when the others went to church; when I had thanked her, she just told me that church bored her.

‘Aha,’ said Jane mysteriously. ‘I am on the track of something.’

She didn’t say any more until we reached the churchyard. Just next to the church door there was a huge yew tree. It looked immensely old — half its branches were broken off and its trunk was as big as a small tower.

‘It’s hollow inside.’ Jane led me around the back and put her hand in. When she took it out she held a sheet of paper, sealed with a blob of sealing wax. She held it out to me.

‘Guess who,’ she said, pushing it under my nose.

It wasn’t difficult. ‘Tom Fowle,’ I guessed. It was in a large bold hand, written on paper that looked torn from a notebook.

‘I suspected this.’ Jane was giggling. ‘Every morning Cassandra writes a letter and then she makes some excuse to go to the church or to the village, but she always goes down here. She and Tom Fowle are using this hollow tree as a letter box.’

I was a bit puzzled. I asked Jane why they didn’t just hand them to each other — they must meet twenty times every day. Mr Austen’s pupils live as if they are part of the family. We meet them at every meal and they are in the parlour every night, playing chess or cards, singing, dancing, or joking and laughing.

‘My mother doesn’t approve,’ said Jane. ‘It would be different if it were Gilbert. He’s the son of a baronet. Tom has three older brothers; he’ll be penniless. He wants to be a clergyman, but it will be years and years before he even has a parish. My father has a parish and a farm but we are still very poor. And Cassandra will have no money. There is no money for any of us. The boys will have to make their own way, but Cassandra and I can’t go in the navy, or become clergymen, so we will have to marry money.’ Jane sounded indifferent, but I could see how she kicked viciously at a clod of earth while she said, in the sort of high, scolding voice that sounded just like Mrs Austen, ‘

Affection is desirable; money is essential.

’ And then her voice changed again, back to the usual

joking tone. ‘Shall we play a trick on them? Write something of our own and put it into the hollow tree instead?’

‘Put the letter back.’ I felt uneasy. Cassandra was the least friendly member of the Austen family. I didn’t know whether it was that she thought I was a nuisance, or whether she didn’t like me very much, but she seemed to look at me in a slightly sour way. I didn’t want her to know that I had been spying on her.

‘Let’s go into the church then.’ Jane tossed the letter back as if she was bored with the whole matter.

The church at Steventon was very old, much smaller and older than the churches at Bristol. There was no one there.

‘Come on,’ said Jane, seizing me by the hand. ‘I know where Father keeps the forms for calling the banns. I love the idea of banns, don’t you? You see, it might be that some wicked baronet is leading some poor innocent girl astray, pretending to be a young bachelor when really he has a mad wife locked away in the attic of his house. If they call the banns the chances are that one of the neighbours will jump up and say, “I know that Sir John Berkley and he is married to my first cousin.” And then a ghastly pallor will come over Sir John’s evil face and he will dash from the church, jump on his horse and ride away, while the gentle girl, Emma, will faint away into the arms of her cousin, who has secretly loved her for many years.’ Jane, as usual, had to turn it all into a story

while she was fishing out some pieces of printed paper from a cupboard in the vestry. I wondered what her father would say if he found her meddling with church property, but then I thought he would probably just laugh. He was very indulgent to Jane. She was, I guessed, his favourite in the family.

‘Who do you want to marry?’ she asked.

I told her that I didn’t know, because I don’t really know any gentlemen.

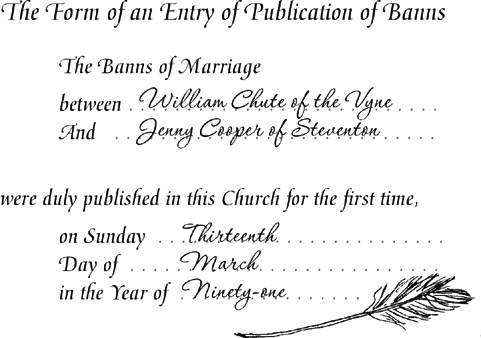

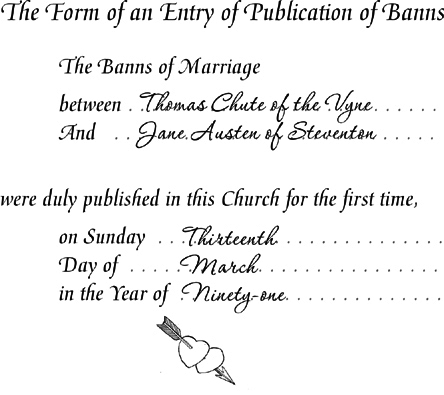

‘I think I’ll marry Tom Chute.’ Already Jane had picked up a quill from a selection lying on the table, dipped it into the inkpot and begun to fill out the form.

I was going to ask who Tom Chute was, but I remembered that he was the boy on the grey pony who was teasing and joking with her outside the inn before the hunt. Then I asked what Jane knew about him and his family — I felt quite grown-up when I said that. It was true though. You couldn’t just marry a man because he made good jokes.

‘He lives at the big house called the Vyne. It’s not too far from here. It’s on the way to Basingstoke.’

‘Have you known him for a long time? My mama always said that you should know a gentleman for at least a year before you allow him to pay addresses to you.’ I said this jokingly. I was beginning to be able to mention my mother without tears coming to my eyes. I seemed to be living in such a different world now, a world of noise and jokes and boys flying around laughing and talking.

‘No, I only met him a few months ago. He will soon come into a large estate and the Vyne. We will probably dine there one evening, so you will see for yourself.’

‘How old is he?’

‘He’s sixteen, just a bit older than me.’

I wasn’t sure that you could really come into a large estate when you were only sixteen, but Jane always has an answer for everything.

‘Yes, of course you can … oh, well, it’s his eldest brother really, but he’s sickly and cross so Tom will

inherit when William dies. I can’t stand William. He’s always trying to make mock of me. Luckily he lacks the wit to do it with any sense.’

‘What does William look like?’

‘You saw him yesterday, at Deane. Do you remember the man on the black stallion, the one holding the horn?’

I was glad that it was quite dark in the little vestry so that she wouldn’t see me blushing. Then I started to laugh. I told Jane that I didn’t think he looked sickly or cross and that I would marry him and then I’d be the one with the big house and the large estate. I told her she could come and stay with me and I’d find her a young man to marry.

‘In possession of a large fortune, I hope,’ said Jane primly, as I seized the quill and began to fill in another banns form — like this: