I Won't Let You Go (11 page)

Read I Won't Let You Go Online

Authors: Rabindranath Tagore Ketaki Kushari Dyson

Silence was maintained by the family and clues were destroyed in such a way that it is nearly impossible to get at the real story behind the tragedy. Beneath the brilliant surface of the family life of the Tagores there were hidden tensions, some caused directly by the uneven process of modernisation which such families were undergoing. Young men were being given all the psycho-sexual stimuli of a vigorous arts education and were being exposed to romantic Western literature with its assumptions of free mixing between the sexes, but were nevertheless being paired off, while at the height of their sexual development, with immature

child-brides

.

All a young man could do in such a situation would be to wait for his bride to reach puberty so that the marriage could be consummated and in the meantime continue to flirt with the wife of an older brother, who might be a young woman closer to him in age. The young women were also being encouraged to educate and develop themselves up to a point, and the pursuit of literature

and music would nurture romantic egos in them as well. Kadambari was artistic, sensitive, and childless. She had married at the age of nine. Jyotirindranath was ten years older than her and is known to have liked the company of his older brother Satyendranath’s wife, the smart Jnanadanandini Devi. There are rumours that Kadambari found letters from another woman,

perhaps

an actress, in the pocket of a tunic of her husband which she was sending to the laundry. There are also rumours that she had made a previous unsuccessful attempt to kill herself. Such

rumours

cannot be authenticated, though clearly some hurt, some

loneliness

must have been gnawing her. She had suffered from some prolonged illness in the latter half of 1883, shortly after the

arrangement

of the match for Rabindranath, in which she participated along with others. In a chapter of one of my Bengali books I have tried to present a retrospective analysis, in the light of the

psychiatric

insights of our times, of the kind of depression that might have driven Kadambari to suicide.

18

Mrinalini Devi in her days as a mature matron.

Jyotirindranath never married again. Rabindranath’s long story ‘Nashtanid’ (The Broken Nest) portrays a situation which was probably modelled on the triangular relationship between

Jyotirindranath

, Kadambari, and himself. There is no suicide. The story was adapted by the director Satyajit Ray for his successful film

Charulata

. It seems highly likely that Kadambari’s suicide was one of those events which provoked Tagore to explore the

situation

of women within the traditional Hindu family in several stories.

Tagore’s writings show that he suffered horribly at first,

undergoing

an inner orphaning, but then began to recover, thanks to his youth and the normal healing processes of nature. At the hour of his devastating grief he could not have received much support from his ten-year-old child-bride, with whom his marriage would not as yet have been consummated, but she reached puberty soon enough and the first child arrived when Rabindranath was

twenty-five

-and-a-half and his wife not quite thirteen.

Some have wondered how a young man like Rabindranath, who was both wildly romantic in his temperament and rebellious in his social ideas, as evinced by his adolescent writings, could have accepted an arranged marriage with a child-bride, but these

contradictions

were part of the times and

mores

. His father wished him to get married, and he did not go against that wish, doing just what his other brothers had done before him. As long as the patriarch Debendranath was alive, Rabindranath’s actual social behaviour remained fairly conservative. He even hurried the

weddings

of his own first two daughters so that his father could see his granddaughters wedded before he died. But it is interesting to note that

after

his father’s death he arranged his son

Rathindranath’s

marriage with Pratima Devi, who was a young widowed girl from a collateral branch of the Tagore family. This was the first instance of widow remarriage in the Tagore family. And Rathindranath was strenuously exhorted by his father to allow Pratima to develop herself fully as a person.

19

Tagore’s favourite niece, Indira Devi.

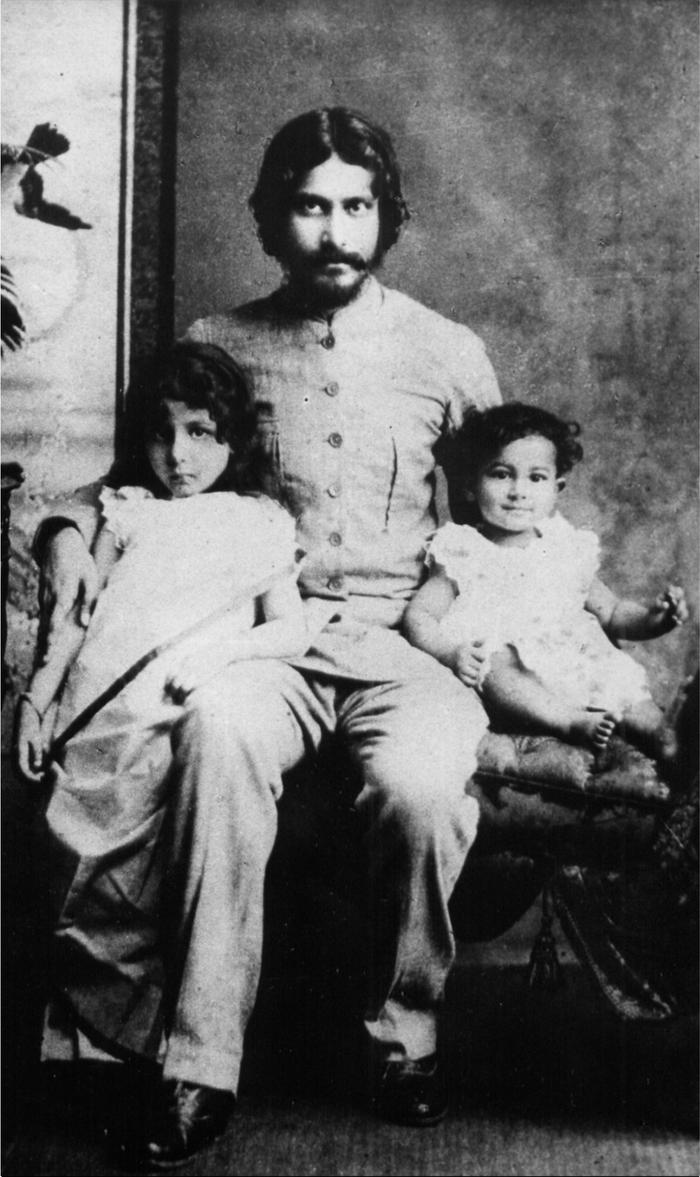

The proud father: Tagore with his two eldest children, Bela and Rathi, in 1890.

Four of Tagore’s five children (left to right): Shomi, Rani, Bela (seated) and Mira.

Tagore with daughter-in-law Pratima Devi in Persia, 1932.

As a bride, then, Mrinalini Devi was not essentially all that

different

from other daughters-in-law who had joined the Tagore family as children. She had already received some primary

education

in her village, and the Tagore family sent her to school and gave her a reasonable education. She learned English as well as

Sanskrit

, and is known to have read the original

Ramayana

with a teacher in order to prepare, at her husband’s insistence, an abridged Bengali version suitable for the use of children. This seems like one of her husband’s educational experiments, a part of his plans for the education of both his wife and his children. The unfinished manuscript has not survived, but her son Rathindranath has recorded that he and his siblings used to read it with great

eagerness

.

20

Her face, on the photographs that have come down to us, looks a little homely, but is not unattractive, and by all accounts she seems to have given her husband the quiet nest he needed to mature as a writer. Gentle, affectionate, and devoted to her

husband

and children, she is known to have been a good cook and an expert manager of household affairs. She supported her husband’s efforts to found a school at Santiniketan and parted with nearly all her jewellery to finance the venture. The few letters from

Rabindranath

to her which have survived, written during temporary stretches of separation, show how solid the foundation of mutual respect and tenderness between the two was, and how anxious he was to remove her and their children from the politics of the extended family and bring them over to a spot where he could share with them the delights and responsibilities of living as a nuclear family. She bore him five children. There can be no doubt that the serene splendour of much of Tagore’s poetry written while Mrinalini was alive and active owes something to the stability she gave him.

Tagore was forty-one-and-a-half when Mrinalini, still a few months away from her twenty-ninth birthday, died of an

undiagnosed

illness on 23 November 1902. He nursed her himself, but could not save her. Rathindranath speculated in later life that his mother might have died of appendicitis, a condition not very well understood in those days.

21

There is every reason to think that Mrinalini would have developed her personality further had fate permitted her to be at her husband’s side for a longer period.

In 1903, nine months after her mother’s death, Tagore’s second daughter, Renuka (Rani), died of tuberculosis. Again, Tagore tried

desperately to save her, but could not. In 1907, Tagore’s younger son Shamindranath (Shomi) fell a victim to cholera while on

holiday

in Bihar. These shattering griefs deepened the religious strain in Tagore’s temperament, consolidating a profoundly religious phase in his development. Basically, it was poems from this phase which won him acclaim in the West. With the death of his firstborn child and eldest daughter, Madhurilata (Bela), in 1918, also from tuberculosis, only two of Tagore’s five children were left alive.

Tagore never remarried and nurtured a core of loneliness within him for the rest of his life. His poems suggest that the wound left in his mind by Kadambari’s death had to some extent healed over when the death of his young wife opened it again. Both deaths left him with a sense of guilt and remorse. Kadambari’s death shook him profoundly, making him suddenly realise how lonely and unhappy she must have been, much more than he had

realised

. Clearly he had not done enough to help her. Nor had he been able to tell her how much he owed her, as a young man and a young poet. It was then too late to make amends. Mrinalini’s death left him feeling guilty too, because he felt he had not shown enough appreciation, while she had been alive, of her quiet devotion and sacrifices for his sake. The two deaths merged into one profound sense of loss, creating the composite ghost of a dead beloved which began to haunt his poetry and songs, investing many of them with a mood of bitter-sweet nostalgia and unconsummated longing. As readers will see, Tagore’s poetry is full of the “unfinished business” of grieving. He often evokes the image of a woman who has gone away, leaving him with the pain of an incomplete

communication

, of things left unsaid.