I Won't Let You Go (10 page)

Read I Won't Let You Go Online

Authors: Rabindranath Tagore Ketaki Kushari Dyson

Annapurna Turkhud, teacher of spoken English to the adolescent poet (prior to his first voyage to England) and inspirer of some of his early poems.

Kadambari Devi.

Tagore in the leading role of Valmiki in his musical play

Valmiki-pratibha,

1881.

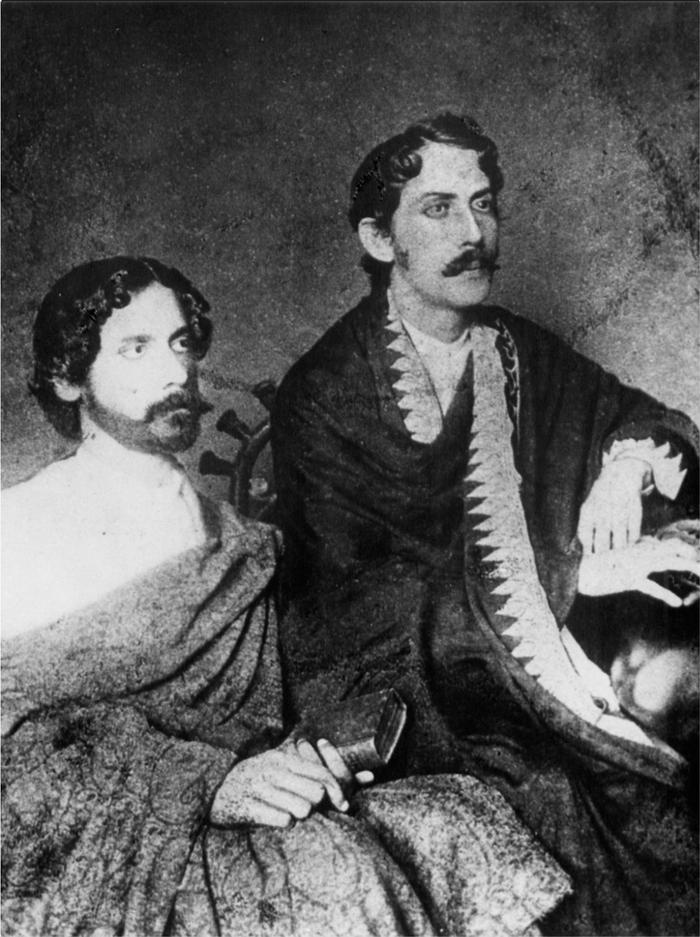

Rabindranath and Jyotirindranath composing at the keyboard.

But the Hindu universe is not unlike David Bohm’s ‘implicate order’, where everything is enfolded into everything and the whole is enfolded into every part.

15

Accordingly, Tagore is just as much aware of the vast universe and its stars as he is of the planet earth and its flora, and readers should be prepared for the vulnerable, girlish earth-mother’s apotheosis and radiant supremacy. She is

the earth, she is all Nature, she is the cosmic maya whose

ultimate

authority we cannot escape.

Ah, greater than great,

you are above, showing your billions of stars,

your moons, planets! Should you suddenly frown

hideously, and lift your thunder-fist,

where would I be, so puny, such a weakling?

So, she-devil, let me decoy you to be a mother!

(‘Hope Against Hope’)

Your creation’s path you’ve spread with a magical net

of tricks, enchantress…

(No. 15 of

Shesh Lekha

)

These poetic utterances spring from a tradition which is not unused to addressing and worshipping God as Mother. I am not anthropologist enough to make a definitive statement on this, but the Bengali Hindus could be among the last “sophisticated” people left on earth whose tradition endorses such an attitude at the

highest

level. In Christianity, the madonna represents the point where the Church has had to yield to the old goddesses, and she has effectively performed the function of a divine mother, but theology has formally denied her full status, holding her to be the Mother of God, but not God Herself. In the calendar of the Bengali Hindus, however, the most important annual festival is that of Durga, who is worshipped as a Supreme Mother. This small but significant difference gives a certain tilt to their culture,

introducing

a tension between a social reality which is largely patriarchal and a cosmic principle which is perceived as feminine, which in turn puts its unique mark on their art and poetry.

Tagore does, of course, address a paternal God as well, and it was mainly a group of poems in that mode through the medium of the English

Gitanjali

that won him the acclaim of the West. Many religious and philosophical strands went into the making of Tagore’s world, and he absorbed the different influences and

mingled

them in the characteristically eclectic Hindu fashion. Such strands include the Upanishadic concept of the seamless unity of the universe, the Baishnab view of the world as the play between Krishna and Radha, the Shaiva image of the cosmos as Shiva’s dance, and the images of the Sufi-influenced Baul sect of Bengal, on which a note has been provided in the Notes section. None of these influences is mutually exclusive, and while acknowledging this rich and complex tapestry of ideas, it is at the same time essential to remember that the poetry itself is without labels.

Tagore with his young wife Mrinalini Devi shortly after their wedding, 1883.

Tagore’s poems and songs do not belong to any closed cult; they record an authentic spiritual autobiography which can be shared by others. It is an open-ended poetic corpus that oscillates in a human fashion between a faith that sustains the spirit in times of crisis, or fills it with energy and joy in times of happiness, and a deep questioning that can find no enduring answers. It is

religious

, not in a sectarian sense, but in the deepest sense. Tagore moves with effortless ease from the literal to the symbolic, from the part to the whole, from a tiny detail to the cosmos. This movement is natural to the Indian mind, and Tagore displays it magnificently. I would like to emphasise that I have chosen poems as poems, not because they exemplify this or that attitude.

Tagore was somewhat lonely as a young boy, being the last

surviving

child of a mother exhausted by fifteen pregnancies. Under the care of family servants, he was often on his own for long hours, daydreaming and amusing himself as best as he could. This initial loneliness did leave a permanent mark on him. When he lost his mother at the age of fourteen, quite a bit of mothering came to him from his sister-in-law Kadambari Devi, the wife of his brother

Jyotirindranath

. Kadambari had entered the Tagore household as a

daughter-

in-law at the tender age of nine, when Rabindranath was seven, and the two had grown up together like siblings. As I have said, she took a keen interest in contemporary Bengali writing, and took an active part in the family’s cultural activities. She was an

important

formative influence on the budding poet.

The adolescent Rabindranath is known to have been stirred by an accomplished young Maratha woman three years older than himself, named Annapurna Turkhud. Vivacious, sophisticated, and fluent in several languages, Annapurna (also known as Anna or Annabai) was the daughter of Atmaram Pandurang Turkhud, an eminent Bombay doctor with remarkably progressive views, and had completed her education in Britain. Rabindranath stayed with the family prior to his first voyage to Britain and had lessons in spoken English from Annapurna. There is evidence that the two were attracted to each other, though Rabindranath was very shy. He gave her the nickname of Nalini, which she afterwards used as a pen-name when she wrote, and she inspired some of his early poetic effusions. She married a Briton named Harold Littledale and died at Edinburgh at an early age in 1891.

16

Tagore never forgot her and reminisced about her in his old age.

Flutters were also caused in Rabindranath’s heart by the friendly daughters of the Scott family, with whom he stayed in London during his first visit to Britain. Of the three sisters, he seems to have been particularly friendly with the second and the third. The third Miss Scott sang and played on the piano, and taught him English and Irish songs. Possibly it was she who expressed a wish to learn Bengali and had lessons from him. It is likely to have been his goodbye to these sisters which was recalled in a tenderly

romantic

poem in

Sandhyasangit

entitled ‘Dui Din’ (Two Days). I was tempted to translate this poem, but in the end did not attempt it.

After his return from England in 1880 the young Rabindranath enjoyed a period when his creative spirit received notable

stimulation

from the friendship and company of his sister-in-law

Kadambari

Devi. He then accepted a marriage that his family arranged for him. The choice was limited, because a girl had to be found from the brahmin sub-caste of demoted rank to which the Tagores

belonged

: other brahmin families would not give their daughters to the Tagores. The girl chosen was Bhabatarini, the daughter of Benimadhab Raychaudhuri from a village in the district of Jessore, a minor official who worked for the Tagore family. The marriage took place on 9 December 1883, when the bride was approximately three months away from her tenth birthday. After the marriage, her old-fashioned name was changed to Mrinalini.

In April 1884, four months after Rabindranath’s wedding, Kadambari Devi, still two-and-a-half months away from her

twenty-fifth

birthday, committed suicide. She is thought to have taken opium and did not die immediately. For two days doctors battled to save her life, but failed. She died on either 20 or 21 April, just a few days before Rabindranath’s twenty-third birthday. The

postmortem

examination was conducted in the Jorasanko house and the Tagore family paid money to stop the news of her suicide from appearing in the newspapers.

17