I Won't Let You Go (5 page)

Read I Won't Let You Go Online

Authors: Rabindranath Tagore Ketaki Kushari Dyson

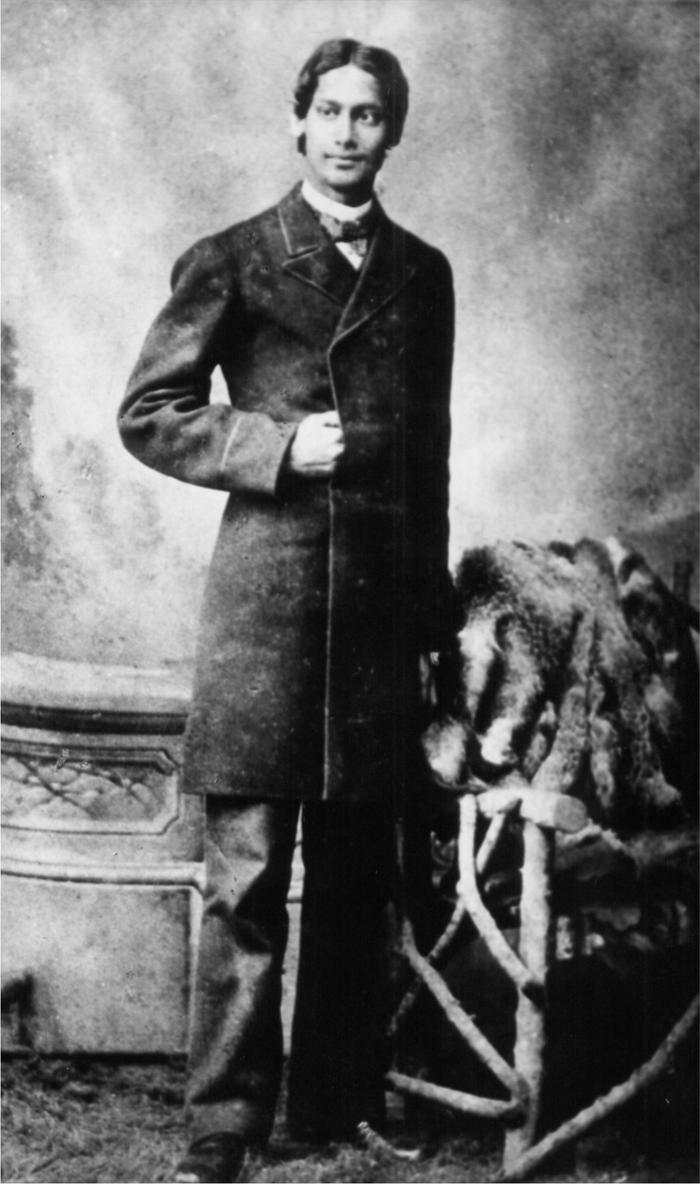

Rabindranath Tagore in Brighton, 1878.

Records left of Debendranath’s wife, Sarada Devi, portray her as a pious woman devoted to her husband and an astute matron in charge of her vast household. She cultivated the habit of reading religious works in Bengali. Rabindranath was her fourteenth child. The fifteenth child did not survive infancy, so Rabindranath was effectively his parents’ youngest offspring.

Many members of the Tagore family are famous in their own right in the annals of Bengal. Dwijendranath, the eldest son of

Debendranath

and Sarada Devi, was an eccentric genius who interested himself in poetry, philosophy, mathematics, and music, among other things. Satyendranath, the second son, became the first Indian member of the Indian Civil Service and was a champion of female education. With his encouragement, his wife,

Jnanadanandini

Devi, became a smart and articulate woman. Indira Devi, the daughter of Satyendranath and Jnanadanandini, was given a

sophisticated

education, married the writer Pramatha Chaudhuri, and enjoyed a close friendship with her uncle Rabindranath.

Jyotirindranath

, the fifth son of Debendranath, was a talented painter, musician, and playwright; his wife, Kadambari Devi, who played a role in the artistic development of her brother-in-law

Rabindranath

, took a keen interest in contemporary Bengali writing, and in the literary, dramatic, and musical activities of the Tagore

household

. One of Rabindranath’s sisters, Swarnakumari Devi, became the first woman writer of fiction in a modern Indian language. The

Tagores ran their own literary workshops and magazines, and wrote and produced their own plays, complete with music. A

collateral

branch of the family, descended from one of

Debendranath’s

brothers, gave India two of her distinguished modern artists: Gaganendranath Tagore and Abanindranath Tagore.

The young Rabindranath stubbornly resisted the formal

schooling

that was available to boys of his social class in Calcutta. He would not settle in any school. Going to school in the morning, learning under pressure, being taught in the medium of English: all these things were irksome to him. His family saw to it that no matter what happened at school, he would be educated at home by tutors. As it happened, he received an incredibly

comprehensive

education at home, from tutors and under the supervision of his elder brothers, an education which was quite comparable to that purveyed by a British public school and which covered

practically

everything from languages, mathematics, drawing, and music, to the natural sciences, anatomy, and gymnastics.

At the age of seventeen Rabindranath accompanied his brother Satyendranath to England. He attended a school in Brighton, but it has proved impossible to establish the exact identity of the institution. At the age of eighteen he enrolled at University

College

, London, and for some three months enjoyed studying

English

literature under the guidance of an inspiring teacher named Henry Morley, an experience he never forgot. He also made

excellent

use of his foreign travels as any young gentleman of culture and leisure would. He observed the society around him, wrote home lively letters full of his observations and relevant comments, listened to Western music, took a lively interest in the young females around him, visited the British Museum, and listened to Gladstone and Bright speak on Irish Home Rule in the British Parliament. Apparently his ‘outbursts of admiration for the fair sex in England caused a flutter among the elders at home’, who deemed it would be unwise to let him live in London on his own, so when Satyendranath returned to India, his brother had to go back as well, early in 1880, without completing his course of study.

4

A second attempt to go to England for higher education in 1881 proved abortive at an early stage.

Fortunately, Rabindranath Tagore was one of those who go on educating themselves throughout their lives. He read widely. His

enlightened

and sympathetic brothers encouraged him to learn at his own pace and discover things for himself. His father taught him to love the

Upanishads

, aroused in him an interest in astronomy

that was to last all his life, and allowed him to combine a literary career, which did not require degrees, with the management of the family estates. Rabindranath was well grounded in the

Sanskrit

classics, in Bengali literature and in English literature, and also familiar with a range of Continental European literature in

translation

. He could read some French, translated English and French lyrics in his youth, and made enough progress in German to read Heine and go through Goethe’s

Faust

. In the end his own extended family and the state of cultural ferment all around him gave him the environment of a university and an arts centre rolled into one. It was in a cultural hothouse that his talents ripened. A man

emerged

, who had his father’s spiritual direction and moral earnestness, his grandfather’s spirit of enterprise and

joie de vivre,

and an

exquisite

artistic sensibility all his own.

Rabindranath Tagore wrote poetry throughout his life, but he did an amazing number of other things as well. Those who read his poetry should have at least a rough idea of the fuller identity of the man. His long life is as densely packed with growth, activity, and self-renewal as a tropical rainforest, and his achievements are outstanding by any criterion. As a writer he was a restless

experimenter

and innovator, and enriched every genre. Besides poetry, he wrote songs (both the words and the melodies), short stories, novels, plays (in both prose and verse), essays on a wide range of topics including literary criticism, polemical writings, travelogues, memoirs, personal letters which were effectively belles lettres, and books for children. Apart from a few books containing lectures given abroad and personal letters to friends who did not read Bengali, the bulk of his voluminous literary output is in Bengali, and it is a monumental heritage for those who speak the language. Like the other languages of northern India, Bengali belongs to the Indo-European family of languages. A cousin to most modern European languages and sharing with them certain basic linguistic patterns and numerous cognate words, it is spoken by an estimated 170-175 million people in India and Bangladesh. When Tagore began his literary career, Bengali literature and the language in which it was written had together begun a joint leap into

modernity

, the most illustrious among his immediate predecessors being Michael Madhusudan Datta (1824-1873) in verse and

Bankim-chandra

Chatterjee (1838-1894) in prose. By the time of Tagore’s death in 1941 Bengali had become a supple modern language with

a rich body of literature. Tagore’s personal contribution to this

development

was immense. The Bengali that is written today owes him an enormous debt.

Throughout his life Tagore maintained a strong connection with the performance arts. He created his very own genre of dance drama, a unique mixture of dance, drama, and song. He not only wrote plays, but also directed and produced them, even acted in them. He not only composed some two thousand songs, but was also a fine tenor singer. He was not only a prolific poet, but could also read his poetry out to large audiences very effectively. Many of his contemporaries have attested that to hear him recite his own verses was akin to a musical experience. Leos Janác˘ek had this experience in Prague and was so impressed and inspired that he wrote a choral work based on a Tagore poem,

The Wandering

Madman

(1922). Another contemporary, Alexander Zemlinsky, based his

Lyric Symphony

(1923) on a set of Tagore poems.

In the seventh decade of his life Tagore started to draw and paint seriously. He has left a substantial output in this field and is acknowledged to be one of India’s most important modern artists.

Tagore was a notable pioneer in education. A rebel against

formal

education in his youth, he tried to give shape to some of his own educational ideas in the school he founded in 1901 at

Santiniketan

near Bolpur (in the district of Birbhum, West Bengal). The importance he gave to creative self-expression in the

development

of young minds will be familiar to progressive schools

everywhere

nowadays, but it was a new and radical idea when he

introduced

it in his school. The welfare of children remained close to his heart to the end of his days. To his school he added a

university

, Visvabharati, formally instituted in 1921. He wanted this

university

to become an international meeting-place of minds, ‘where the world becomes one nest’, and invited scholars from both the East and the West to come and enrich its life. Under his

patronage

, the Santiniketan campus became a significant centre of Buddhist studies and a haven for artists and musicians. It was here that the art of

batik

printing, brought over from its Indonesian homeland, was naturalised in India.

Through his work in the family estates Tagore became familiar with the deep-rooted problems of the rural poor and initiated

projects

for community development at Shilaidaha and Potisar, the headquarters of the estates. At Potisar he started an agricultural bank, in which he later invested the money from his Nobel Prize, so that his school could have an annual income, while the

peasants

could have loans at low rates of interest. He had his son Rathindranath trained in agricultural science at Illinois, and in the village of Surul, renamed Sriniketan, adjacent to Santiniketan, he started an Institute of Rural Reconstruction with the help of a Cornell-trained English agricultural expert, Leonard Elmhirst. The kind of work that was begun here has since then been repeated and elaborated in many programmes of self-help in India. For instance, Sriniketan pioneered the manufacture of hand-crafted leather purses and handbags, a cottage industry which has, since then, taken off elsewhere as well and now exports products to many parts of the world. It is not an exaggeration to say that the Santiniketan-Sriniketan complex became an important cultural institution in twentieth-century India. Tagore’s friend Leonard Elmhirst went on to give shape to an educational institution of his own at Dartington Hall in Devon and has always acknowledged the inspiration he received from Tagore.

Tagore with Leonard Elmhirst at Dartington, 1926.

Though Tagore was not a systematic philosopher, he is of

considerable

contemporary relevance as a thinker, one of those farseeing individuals whose ideas show us the way forward in the modern world and who are going to gain importance as time

passes

. Those who are interested in ‘deep ecology’ should find him a very congenial thinker. A ‘Green’ to his core long before the term was coined, he was what is nowadays called a holistic thinker, never forgetting the whole even when concentrating on the parts. His Upanishadic background made him constantly aware of the interconnectedness of all things in the cosmos. He saw human beings as part of the universe, not set apart from it, and knew that the human species must live in harmony with its natural environment. An outspoken critic of colonialism, he was at the same time in favour of international cooperation – genuine

cooperation

, not one country exploiting another in the name of

cooperation

. Always deeply appreciative of the solid achievements of the West, he criticised the West for its fragmented, mechanistic

approach

to reality, its scheme of values which overrated material power and underrated other human assets. Likewise, he was acutely aware of the limitations of merely traditionalist thinking in his own country. Although he went through a phase of looking back with nostalgia at India’s past glories, he was never fatuous about it and quickly outgrew any attitude that was purely and ritualistically nostalgic. No one could be more aware of the elements in India’s heritage that needed to be cherished and preserved, but at the same time he knew that many things had to be changed. Some of

his most powerful satirical writings are directed against those who oppose necessary changes. He knew that political independence alone was not an adequate goal for his country, that the real task lay at grassroots level, of transforming and energising the rural masses through education and self-help programmes. He

welcomed

modernisation in many areas of life. For instance, he

supported

artificial contraception, which Gandhi opposed.