Iceman (23 page)

Authors: Chuck Liddell

WE'RE FIGHTERS. A LOT OF US HAVE ISSUES.

T

HIS SHOW WAS JUST LIKE ANY JOB. DANA CALLED

us back to the training center for speeches at 10:00

P.M.

and meetings at noon. We were training these guys twice a day, and we went for fifty-eight days straight. No one trains that many days in a row. I was responsible for someone else's schedule, seven days a week, and was on call whenever I wasn't at the training center. One night during taping, Antonio was fighting in Reno. I had arranged for a plane to take a bunch of us from Vegas to see him fight. But Dana and the producers told me I couldn't go. I wasn't allowed to leave lockdown, even to see one of my guys fighting. All for a show no one was sure would air anywhere.

The only time we saw footage of the show was when Chris, the kid who pissed on a roommate's bed the first night, was nearly kicked off.

After the guys had been in the house a few weeks and were going stir-crazy, Dana decided to take everyone out for dinner and to get drunk. Some guys drank more than others. Chris, Josh Koscheck, and Bobby Southworth certainly did. Chris and Koscheck, both middleweights, had been ripping each other the entire show. They clearly hated each other. Southworth, a light heavyweight, and Koscheck were best friends in the house. Late that night Southworth started going at Leben, eventually telling him he was a “fatherless bastard.” Up until that point Chris had never backed down and usually instigated every confrontation in the house. But Bobby crushed him. Chris just put his head down and started crying. He was so upset he couldn't even sleep in the house. Instead he took his blanket and went to sleep on the front lawn. That's when Koscheck and Southworth decided to fuck with him some more. While he was sleeping, they turned on the hose and sprayed him.

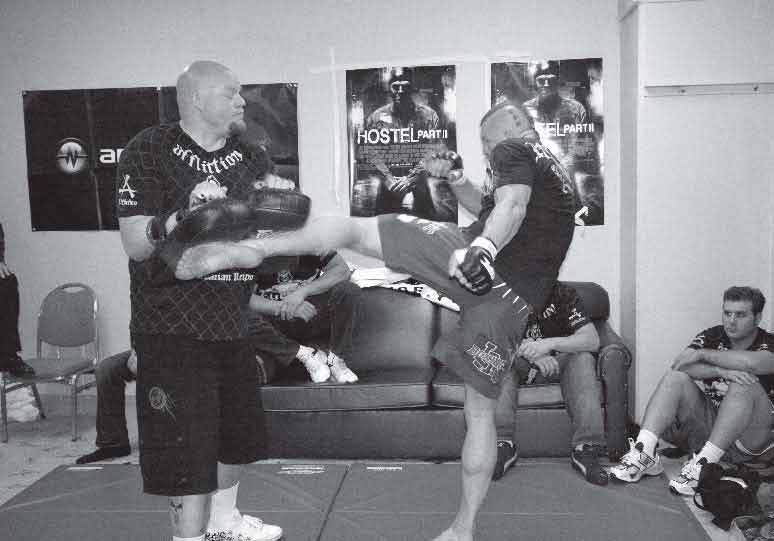

Every fighter needs to warm up before a fightâeven a champion.

This sent Leben over the edge. He punched a hole through the glass in the front door, slicing off the skin on his knuckles, then tore down one of the bedroom doors. Blood was all over the wall and splattered on the floor. It was nasty.

Of course, Dana got a call about the incident around seven in the morning. Then he called Randy and me into the training center. This is what overnight-summer-camp counselors must feel like. We talked about kicking Koscheck off the show, and about kicking Southworth off, too. When we got to Leben, though, I didn't think he deserved it. He needed a thicker skin for sure. UFC opponents will do worse things than call you a “fatherless bastard” and pour water on you. But, as I told Dana, “Chris has issues. But who doesn't? We're fucking fighters. A lot of us have issues.”

Then we decided to settle it the way we settle everything else: in the cage. Koscheck versus Leben. Too bad for Chris. Koscheck, a former NCAA wrestling champ, got him on the mat and never let him up.

Despite the workload, which I wasn't used to at all, working the show had its benefits. It reminded me of one of the things I love about mixed martial arts, which was teaching younger guys. I was their coach, and I started to feel protective of them, which led to some intense screaming matches with producers. Before one fight, the tape guyâthe one who wraps up a fighter's hands before he puts on his glovesâshowed up late. By the time he was done, my fighter barely had a chance to warm up before a producer was in the dressing room telling him he had to go out and fight. Now, these fights weren't live. They could have waited a few more minutes for him to finish preparing. He was the one who was competing for his life, not the producer. So I told her he wasn't ready, and she lost it on me, as if I were one of the production assistants. I'm a grown man, you can't talk to me like that. Besides, I told her, I was hired to teach these guys how to fight and to take care of them. I'm going to defend them as if they were fighting for me and Hack at The Pit. When she still wouldn't back down, I finally said to her, “Okay. Go talk to the guys who pay for the show and ask who they want, you or me.” That ended the fight. And my guy got to finish his warm-up.

Most of us in the UFC stick up for each other because, except for jackasses such as Tito and Vernon White, we are a collegial group. We help each other when we train, teach each other new moves, explain how to improve various aspects of each other's game. We respect everyone who is giving it a go, no matter how talented he is. That's because so many guys who study martial arts do it for reasons other than wanting to kill people with their hands. They're interested in pushing themselves, taking on a challenge to learn as much as they can in sports that are thousands of years old and constantly evolving. The jujitsu specialists or karate experts in the UFC still have a passion for those disciplines that moves them to teach, even if they're helping someone who may one day be an opponent.

It was the same way with these guys. The strikers gave tips to the grapplers. The wrestlers taught kickboxers how to sprawl and avoid takedowns. Submission guys explained how to break out of choke holds. When those guys faced each other in the cage, they wanted to kill each other. But when they were on the mat at the training center, they were as concerned with helping each other as they were with helping themselves. I don't know that every sport is like that.

There were two other positive side effects: First, all the downtime allowed me to have my knees examined. I had torn the MCL in one knee before the first Randy fight, and the other one had been nagging me for a long time. The doctor told me that a decade earlier he would probably have put me under the knife to fix them both. Now, he said, I could just ice it aggressively and be fine. By my doing ice baths after every workout, my knees were pain-free for the first time in years.

Second, halfway through shooting, I started dating the show's host, Willa Ford. It happened by accident. Willa wanted to go out, but she wasn't allowed to hang out with any of the fighters. So Dana told me to take her out and show her a good time. Pretty soon we were together all the time. The show wasn't even picked up yet, but I was already reaping the benefits of being on television. My girlfriend was a pop star whose biggest hit was called “I Wanna Be Bad.” She was one of

Maxim

's one hundred hottest chicks and a future

Playboy

model. When we finally got to go out with the fighters on the show the last night of taping, we all ended up in a strip club. Willa was pretty loaded, and somehow the guys coaxed her onto the stage to do a dance. While she was letting loose to “Pour Some Sugar on Me,” her shirt was ripped off by one of the dancers. A stripper said to her, “Nice tits.” Willa answered, “Thanks, you, too.”

Really, I didn't have much to complain about.

SOMEONE UP THERE HAS A GREAT SENSE OF HUMOR

A

S SOON AS THEY STARTED EDITING THE SHOW

,

Dana says he knew it was gold. Now he just had to sell it. Luckily, as much as the UFC lived by an oh-screw-it mentality, so did a TV network geared toward the UFC's audience: Spike TV.

Spike was like one of those lad magazines come to life. It branded itself as the “first network for men,” and it launched with a party at the Playboy mansion. In the beginning it aired adult-oriented cartoons and reruns of

The A-Team

as well as Pamela Anderson classics such as

Baywatch

and

V.I.P.

Spike even copied the

Maxim

and

FHM

model of the Hot 100 issues and aired an original special called

The 100 Most Irresistible Women

.

The networkâwhich began as the Nashville Network in 1983 and then became the forgettable TNN before being renamed Spike in 2003âcould afford to take chances. So few people were watching and its programming was so targeted, if one of its shows drew 1.5 million viewersâhit shows such as

Grey's Anatomy

pull in between 20 and 30 millionâit was considered a huge hit, especially with advertisers. There's not a more coveted group for the guys selling stuff than men between the ages of eighteen and thirty-four. Luckily for the UFC, those are our fans.

Spike had had success airing pro wrestling. And in yet another stroke of good luck, Spike's contract with the WWE was coming to an end in the middle of 2005. Rumors were that it wasn't going well. If the network was looking for something to get on the cheap and hope it could pick up where wrestling left off,

The Ultimate Fighter

was a nice alternative. So when Dana came by with a show that featured roommates peeing in each other's bed, guys punching out windows and doors, and real fights in which guys were bloodied and then sent home, how could they resist? Especially since Dana and the Fertittas had paid for it all, which meant it would cost Spike nothing. They agreed to put it on the air in January 2005. It was a barter deal, which meant they provided the airtime, but Dana had to find the advertising. For the first two shows, almost no one wanted to buy a piece of it.

The network had pretty low expectations. It didn't do any promos for the show. And most of the reviews that came in were filed under the “other new shows” category. Only the papers from towns that had fighters on the showâsuch as the

Boston Globe

(Alex Karalexis, Kenny Florian, Chris Sanford) or the

Augusta Chronicle

(Forrest Griffin)âgave full write-ups. Even then, it was about the fighters defending the sport, explaining that the days of bare-knuckle brawling were over. From the inside it always seemed as if we were making headway into the mainstream, then the media would write stories like that and we'd be reminded that most people still thought of us as nothing more than thugs.

The show debuted on January 17, 2005, at 11:00

P.M.

Immediately the headlines changed. “

Ultimate Fighter

Surprise Hit for Spike.” “

Ultimate Fighter

Knocks Out Competition.” Somehow, people found the show. Nearly 2 million people watched the premiere, almost half of them men between eighteen and forty-nine. In the eighteen-to-thirty-four age group, a little less than four hundred thousand guys watched the show. I don't think anyone realized how starved the fans were for something like this. So many gymsâdojos, kickboxing schools, jujitsu academiesâwere buying UFC fights on pay-per-view, then inviting forty students to come and watch. Imagine if all those kids were now watching the fights for free. The numbers improved nearly every week. Mixed martial arts was breaking through on basic cable TV, just a few years after it had been declared dead and less palatable to broadcasters than porn. It wasn't just the fights that drew people in. It was the fighters. They weren't at all what people expected. Sure, they were aggressive and eager to fight. But they were college-educated. They spoke in complete sentences. They trained as hard as any other professional athletes. As Dana once told

Playboy

, “Suddenly people were watching mixed martial arts without realizing they were watching it, because they got caught up in the story lines. You also get to learn about the characters and see that these guys aren't a bunch of fucking gorillas who just rolled in off a barstool. You can see how hard they train and that they have real lives and families.”

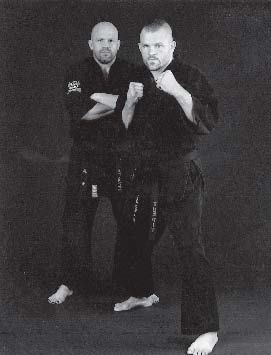

Some people think UFC fighters are a bunch of street thugs, but many of us are highly skilled martial artists.

Too bad we couldn't sit back and enjoy it. Despite pulling such big numbers for the network the first couple weeks, Spike had yet to pick up

Ultimate Fighter

for a second season. Paying $10 million again to produce it themselves was out of the question for Dana and the Fertittas. They wanted a deal with a network that was going to pay them. This was the biggest hit Spike had had in its most recent incarnation, so it seemed like a no-brainer. Then, at the end of January, it became obvious why nothing had been done. The head of the network resigned because of “creative differences.” A new guy was coming in, and no one knew what he wanted to do. In fact, people were too worried about their own jobs to be negotiating rights deals. They were practically hiding under their cubicles, hoping to stay out of the way and not get canned. Meanwhile, Dana was flying to New York twice a week trying to make sure Doug Herzog, Spike's new boss, had

Ultimate Fighter

on his radar.

He did, of course. How could he not? The ratings were improving every week. In mid-March Herzog announced Spike wasn't going to renew its deal with WWE, but was working toward a second season of

Ultimate Fighter

. Negotiations dragged on for weeks. The night of the finale, while Stephen Bonnar and Forrest Griffin fought, Dana was putting the finishing touches on a deal in the alley. He and Herzog's rep from Spike actually agreed to air a second season from the fucking alley during the last fight of season one. We'd spent all this time trying to prove we weren't just back-alley brawlers, and then that's where the deal that finally proves it gets hammered out. Someone up there has a great fucking sense of humor.

If Dana had held out a little big longer, who knows how much more money he could have made. Because the ratings for the finale weren't just better than they had been for the season premiere. They were the highest ratings Spike had ever had. In every category that was importantâoverall viewers, eighteen-to-forty-nine-year-old males, eighteen-to-thirty-four-year-old malesâthe numbers went up, peaking in the last show of the year. We wound up averaging 1.7 million viewers per night. The size of the audience grew nearly 20 percent during those first twelve weeks. In April, when the finale aired, Spike was ranked the number-one network overall among men eighteen to forty-nine and eighteen to thirty-four. That finale, which aired on a Saturday night in prime time and drew more than 3 million viewers, was not only Spike's biggest show, but the most watched show among men that night. More people were watching UFC fighters on Spike than watched NBA games on ESPN.

Not only had we got the exposure we wanted, we were a television phenomenon. And the timing couldn't have been better. A week after the finale aired, with a bout that more people watched than any other in UFC history, Randy and I were going to have our rematch.

This time I'd be ready.