If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor (51 page)

Read If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor Online

Authors: Bruce Campbell

Tags: #Autobiography, #United States, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts - General, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Actors, #Performing Arts, #Entertainment & Performing Arts - Actors & Actresses, #1958-, #History & Criticism, #Film & Video, #Bruce, #Motion picture actors and actr, #Film & Video - History & Criticism, #Campbell, #Motion picture actors and actresses - United States, #Film & Video - General, #Motion picture actors and actresses

-Y-

- Yarn -- Wool

- Yield (sign) -- Give Way

-Z-

- Z -- Zed

- Zero -- Nought

- Zucchini -- Courgette

47

SUITING UP

During the run of

Brisco,

and subsequent TV shows, I often found myself thinking, sometimes out loud,

I wouldn't have done it that way,

or

Man, nobody knows what's going on, why doesn't this director communicate?

The cancellation of

Brisco,

in the spring of 1994, silenced my inner monologue. Suddenly, I was a free agent, so I decided to toss my hat into the uncharted waters of directing.

It wasn't a tough decision -- I had been behind the scenes for fifteen years in various production capacities and knew my way around a film set. I can't say that I grew up with an overwhelming desire to emulate John Ford or Alfred Hitchcock -- I was led toward directing so I could be the director I always wanted as an actor.

The job, as I have observed, requires a challenging blend of technological know-how and gut instinct -- at least that's what I told Rob Tapert, now executive producer of

Hercules: The Legendary Journeys.

"C'mon, Rob, how bad could it be? Send me down..."

The badgering was successful, and I made my way to the Southern Hemisphere to direct episode nine of the first season.

The word

director

conjures up all sorts of clichés -- usually those of a hard-charging tyrant, clad in jodhpurs, barking orders to a subservient cast and crew. The director is indeed a captain... of sorts.

Running with the nautical analogy, he or she is looked upon by a large crew to steer the ship. However, regardless of what you have heard, this able seafarer is, by design, at the helm of

someone else's ship.

This vessel is either seaworthy or a leaky tub. Initially, the design is in the hands of writers -- if they are clever, a clear course is charted and the ship is hardy enough to weather the storms of inept directors and misguided producers. On the other hand, a weak hull punctures easily and the ship will soon find itself beached, regardless of the skipper.

Producers finance the shipyard -- if they're boat lovers, their ships will inevitably become the envy of the nautical world and any captain would be proud to take the wheel. Pound-foolish producers, on the other hand, crank out ships that only morons or greenhorns would command.

In the case of television, the director-of-the-week is often stepping into territory familiar to everyone except themselves. Sets, cast, crew and script are all decided well in advance. In this case, a director takes on the role of Enhancement Coordinator, Star-Coddler, Cheerleader, or Fall Guy.

A director under these circumstances must simply strive to get the best use out of the elements provided -- to avoid rocking the boat, if you will, and return it safely to port for the next poor slob.

Josh Becker found the challenges of directing TV different from the independent world of filmmaking:

Josh: It's fun, but it's not the same thing as trying to actually exert your ability. The only real ability I'm getting to exert in TV is

how fast can you go?

Bruce: Right, but I have to say, it's an excellent proving ground -- a place where discipline rules the day...

Josh: I agree -- I'm glad to know I can do it, and I really believe that if you can do

Xena

or

Hercules

you can do anything.

On a TV schedule, there are only so many ways to get five to seven pages shot (otherwise known as "in the can") per day, particularly in a fixed shooting period. A keen eye for composition isn't necessarily going to bail you out when a prop doesn't work or the weather suddenly turns foul. I've been directed by plenty of "shooters" (an industry term for directors who have a distinct visual style) who didn't have the first idea about blocking, storytelling, or even how to talk to actors. At the same time, an "actor's director" isn't going to succeed if he shows up on set with a bag full of motivations but no idea how to commit it all to film.

The first hurdle of directing a

Hercules

episode was remaining awake after a twelve-and-one-half-hour red-eye flight from Los Angeles to Auckland. The only successful way to adjust to this new time zone (technically

tomorrow,

minus a few hours) was to stay awake until that evening -- it was just as well, since my first meeting was 10:00 that same morning.

After stumbling through a blitz of meetings, each with a multitude of questions from every department, my next goal was to test the waters of the leading man, Kevin Sorbo -- was he Demanding? Egotistical? An idiot?

The only way to find out was to sneak onto the set of the current episode shooting and watch from the shadows. You can learn a lot from the "vibe" of a set -- a lot of shouting tells you that the crew is either behind, or they have bad leadership. A deathly quiet set is deceiving because it either means all is well, or there's a lot of tension.

As I entered the stage, affectionately called 911 (for its address), the set was very, very quiet. I tiptoed to a dark corner and watched Kevin squaring off with a centaur -- half man, half horse. The take seemed to go well and the director printed it. Immediately, Kevin's face brightened and the set became a cheery buzz of activity.

Okay,

I thought.

So far, so good.

When I was introduced to Kevin, he was relaxed and gracious -- another good sign. I figured Kevin wouldn't want to pussyfoot around, so I got right down to business.

Bruce: Hey, uh, Kevin, I wanted to get together with you at some point and go over the next episode.

Kevin: Good idea -- do you golf?

Bruce: G-g-golf? You mean with clubs and everything?

Kevin: Yeah -- they have a lot of good courses around here.

Bruce: Uh... sure... I golf...

Kevin: Cool -- how's Saturday?

So, our first "meeting" was on the golf course. Thankfully, Kevin and I had a lot in common -- having just come off a series myself as a single male lead, I could relate to his workload.

By the time we reached the second hole, I knew Kevin was going to be great to work with -- I had lost my fourth ball and he was still in good spirits. Kevin is, in fact, an excellent golfer, but it didn't affect my game plan one bit -- for the good of the show, I let him win.

Following the first take of the first shot of the first episode I ever directed, I forgot to call

cut.

Sitting behind a portable monitor, concentrating on the scene at hand, I simply became lost in the act of watching television. George, my sarcastic assistant director looked over at me after the actors were done with their dialogue.

"So... that would be...

cut

?"

"Right... cut! Cut!"

I yelled, as I leapt, mortally embarrassed, from my chair.

The challenges, aside from developing an attention span, are many for a director, and in New Zealand, they were somewhat unique.

With the two lead actors sporting long hair (Kevin Sorbo and Michael Hurst), I was encouraged to find locations that weren't overly windy -- dramatic confrontations don't always work when you can't see the hero's face. The frustration, of course, is that visually speaking, higher elevation locations looked more dramatic and offered greater depth and scope.

On any given shooting day, Hercules and his sidekick Iolaus might stroll down a shady lane (known as a "walk and talk"), wake up in a campground, fight a monster and toss a pre-Hellenic football around. Technically, that's four locations, but the transportation department won't tolerate four company moves -- therefore, it became a game of,

How close can the next location be?

In many cases, the answer was as simple as pointing the camera 180 degrees in the opposite direction.

Once you actually start filming, new challenges present themselves. Just when you had everything figured out, an actor would ask a question about motivation, a prop would break, or an hour-long downpour would commence -- that's when the job of director gets truly creative.

But, let's not forget the delicate issue of deciding which shot to use in the final version. In one take, the actors might absolutely nail the dialogue, but the camera was out of focus in a specific part. In another take, the acting might only be serviceable, but the dolly move was dead on. What to do?

In these cases, I tend to print both takes and work out the problems with the editor in postproduction. Editing is a beautiful and powerful thing -- during that process, now wonderfully controlled by computers, you can edit around a jerky camera move, tighten an unwanted pause from an actor, or remove a useless shot.

In the hour-long format, commercials take up eighteen minutes (by the time you read this, it'll be longer), so the director must also allow enough time to get all those Budweiser and Chevy Truck spots in.

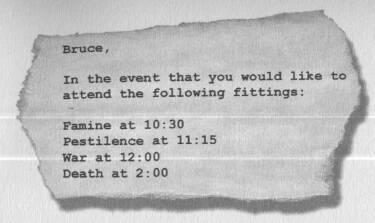

Aside from the obvious nightmares, there are many pleasures to be found in directing. Where else would you get a memo from the costume department that reads like this?

48

LEATHER AND MACE:

ACTING IN A PARALLEL UNIVERSE