If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor (48 page)

Read If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor Online

Authors: Bruce Campbell

Tags: #Autobiography, #United States, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts - General, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Actors, #Performing Arts, #Entertainment & Performing Arts - Actors & Actresses, #1958-, #History & Criticism, #Film & Video, #Bruce, #Motion picture actors and actr, #Film & Video - History & Criticism, #Campbell, #Motion picture actors and actresses - United States, #Film & Video - General, #Motion picture actors and actresses

This became evident with the film

Congo.

I met with director Frank Marshall to con him into giving me the lead role, ultimately played by Dylan Walsh. I did my best to sell Frank on the fact that I was the guy for the job, the right one to sweat with him in the jungle. Frank was unconvinced, but kindly offered up the small, dead-in-five-minutes role of Charles.

Sometimes Hollywood is like a game show -- if you don't win the brand-new car, you get a toaster. Who was I to argue with the man who used to produce all of Steven Spielberg's films? Where do I sign?

There was a distinct advantage to being a small cog in a very big wheel, and

Congo

was one of those situations where it was almost impossible to complain about being an actor. The amount of days it took to film my character was of little concern to a company that had to deal with issues like airlifting tons of film equipment to the base of one of the most active volcanoes in the world.

Standing at the base of the Arenal volcano with Frank Marshall, I joked that, maybe next time, he could find a place a little more remote.

"This is nothing," he stated plainly. "Try and get catering in the Sahara Desert." He was referring to a Spielberg epic he produced and I could tell that he wasn't joking.

In the film, my character leads an ill-fated expedition deep into the bowels of the Congo. A

second

expedition, with the principle actors, passed through the same areas, but had to stop and confront some challenge every step along the way.

On a practical level, this meant that shooting the first expedition required only a couple of shots in each location, while the second team invariably filmed for days on end.

For the actors in this first expedition, an excellent scam presented itself. Call sheets were posted outside the hotel production office at 5:00 P.M. every day. If the world "hold" appeared next to our name, it meant that we weren't needed the next day, and we'd race over to a travel agent, open until 7:00, and book an excursion.

I'm only half guilty to announce that, complements of Paramount Pictures, I white-water rafted, body surfed on pristine beaches, and tramped through nameless jungles tracts, surrounded by 5,000-year-old trees.

I often get hassled by fans about why I did that film. The thing that many folks don't understand is that an actor doesn't always do things for art. I would have

paid

to go to Costa Rica, and yet I had a chance to not only go there for free but get paid as well.

Escape from L.A.

was familiar terrain and it was a chance to work with John Carpenter, whose film

Halloween

convinced us that the horror genre would be a viable choice for our first film.

In the two days that I worked on

Escape,

John only gave me one piece of direction. In a very friendly but direct way, he lowered his voice and said, "Bruce, I want this dead straight." He must have been in collusion with Sam Raimi.

The real plus of playing the surgeon general of Beverly Hills was working with one of the best special-effects makeup guys in the business: Rick Baker. Because my role was that of a twisted freak, Rick patterned the look after the more celebrated plastic surgery mistakes in Hollywood.

The character wound up with a tight, ski-slope nose, an obvious facelift, some collagen implants, Movie Star teeth, plucked eyebrows, and hair plugs, not unlike a Ken doll. The results were subtle, yet alarming -- and took five hours to complete.

The other cool thing about working on big-budget films is that you go toe-to-toe with big-shot actors -- Kurt Russell, in this case. I always had a lot of respect for Kurt -- he had been around for a long time and I recalled seeing him in episodes of

Lost in Space

and even

Gilligan's Island

when I was a kid. It was nice to see him finally get his due as a big-buck, leading man.

I went to the set in preparation for my scene with Kurt and I spotted him chatting casually off in the corner. He was acting like he had just dropped by the set to see what was going on and happened to wind up in the film. When I introduced myself, he got a kick out of my makeup, but he was interested in something else.

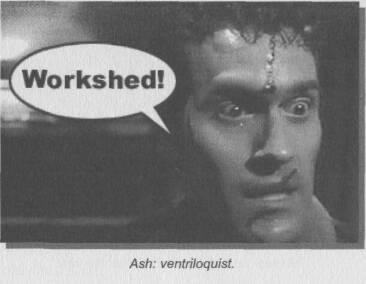

Kurt: Hey, Bruce, say, "workshed."

Bruce: (incredulous) What?

Kurt: From

Evil Dead II.

Bruce: Yeah, I know that, but how do you know that obscure line?

Kurt: My son is a big fan of that film. For some reason, he wanted me to have you say it.

Kurt was too polite to mention that "workshed" was an obvious overdub to the film, my mouth doesn't move at all during that line and it's a point of great ridicule on college campuses around the country.

Sometimes, an actor takes a role because he or she thinks it will advance their career. Other times, it will be to fulfill an artistic longing or to simply make a big payday.

McHale's Navy

would fall into the "none of the above" category. One day, I got a call from my manager, Robert Stein.

Robert: Bruce, something's come together that's really exciting.

Bruce: Cool, what is it?

Robert: It's a supporting role for Universal.

Bruce: Cool, what is it?

Robert: Bryan Spicer (who did the

Brisco

pilot) is going to direct it.

Bruce: Cool, but like I said...

what is it?

Robert:

McHale's Navy.

Bruce: The old TV show? They're gonna remake it?

Robert: Yes. There's a part Bryan wants you to play.

Bruce: Who?

Robert: His name is Virgil -- one of the sailors. This part is really something you could have fun with. I'll send you the script.

When any script arrives, I always do a simple test to see how much dialogue my character has -- I flip through the pages like I'm shuffling a deck of cards and try and spot the character's name in dialogue scenes. If it's easy to spot as I whiz along, it means that I have a lot of dialogue and often, it's a big role. When I finished the test for

McHale's Navy,

I was surprised to note that I never spotted the name Virgil.

Must have missed a few pages,

I thought.

Better try this again.

I leafed through the pages more slowly this time and caught a fleeting glimpse of Virgil early in the script, before the name disappeared from the radar screen entirely.

Finally, I sat down and read the full script. From an actor's point of view, the warning signs were everywhere:

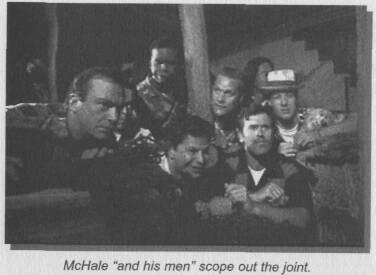

McHale "and his men" search the area.

McHale "and his crew" go to Cuba.

McHale, "and the others" get off the boat.

The translation of that meant that I'd have many days with nothing

specific

to do. I recalled a brief conversation with Liam Neeson while he was looping

Darkman.

Bruce: Hey, Liam, I caught the end of

The Bounty

the other day and I could have sworn that was you.

Liam: Yes, it was.

Bruce: Who were you?

Liam: I played the guy over Mel Gibson's left shoulder.

Bruce: What do you mean?

Liam: Well, I was one of the sailors. My big challenge each day was to see which of Mel's shoulders I could get behind. Usually, I wound up behind the left one.

With these omens, I called my manager in search of a logical reason why I should be in this film.

Bruce: Robert, I just read the script.

Robert: Funny, isn't it?

Bruce: Yeah, a

Laff Riot,

but there's only one problem.

Robert: Oh?

Bruce: My character doesn't do anything.

Robert: Well, they're going through a major rewrite right now, and Bryan has some big plans for beefing up all of the sailor parts.

Bruce: Do you really think anything's going to change?

Robert: Yes, I do. I think we should do this.

The reality of motion pictures is that the screenplay writer will concentrate their effort on the largest three or four characters, showering them with finely honed dialogue, endearing character traits and a full dramatic "arc." When you're lower on the "screen time" food chain, you get what falls from the table --

McHale's Navy

was all about table scraps.

I decided to at least do the basic actor prep stuff -- find out what I can about this thing called the navy. I had my trusty assistant, Craig, drive a few hours south of LA to pick up a copy of

The Bluejackets' Manual,

the official training manual of the United States Navy -- Anthony Hopkins, eat your method heart out.

Upon delivery of this navy "Bible," I sat, with highlighter in hand, marking anything interesting, pertinent, or quirky. There were heaps of useless tidbits, but at first glance it appeared that there was no practical use for them in the film.

After rereading the script, I noticed a scene where McHale's crew stages a "telethon" to jam the radio signals of the bad guy, played by Tim Curry. The only thing the script actually specified, however, was that Virgil "jammed" on the drums.

I had no idea how to play the drums, so I hastily arranged lessons with a man at his house in the San Fernando Valley. My sweaty, shirtless teacher led me to his ratty drum set.

"Okay, junior, let's see your stuff."

I showed him what I knew about playing drums, which didn't take long, and he walked me through a couple of basic drum exercises. After ten minutes, he rolled his eyes and grabbed my sticks.

"You will never be a drummer," he stated flatly. "Give me the check."

Despite the knowledge imparted by this gifted teacher, it was ultimately decided, on location, that there would be no band.

Instead, a talent show was devised for the climax of the film, but there wasn't any description beyond

Virgil and Happy

(played by French Stewart)

are on stage performing.

I knew I was on my own and I sure as hell didn't want to be caught improvising something at the last minute on set, so I dug up that navy manual and came upon a passable angle. Nautical terms like "Poop Deck," "Bull's Nose" and "Breast Line" seemed to cry out for some kind of vaudevillian bit.