If These Walls Had Ears (21 page)

Read If These Walls Had Ears Online

Authors: James Morgan

That, at least, is the way she felt about it at the time.

It’s a funny thing how a relationship with a house can be so much like a love affair. At first it’s all magic, all rockets

in flight. Then, sooner or later, the reality sets in. If it’s not going to work, the realization sneaks up on you gradually,

moving from the feeling to the knowing, the way the awful need to end a marriage does.

The Grimeses were the first of several families to divorce this house. By that, I mean several families left it not just to

go

toward

something better; they left it mainly to get away from this house’s incessant misery, its overwhelming neediness. They left

it to save themselves. But inevitably, such a break leaves scars on both sides.

Rita was twenty-three and already the mother of three when she and Roy moved to 501 Holly. The year was 1966, the month September.

As young as she was, she knew even then that she loved old houses. She thought of the one she had grown up in as “the old

home place,” imbuing it with a magical quality that transcended mere brick and mortar. In the mid-sixties, however, she had

been living with her husband, Roy, and three young children in an 1,100square-foot house in a new subdivision of houses all

pretty much like theirs, all occupied by people pretty much their age. The house had actually been built for them, though—the

developer showed them the lots they could choose from and then let them pick from among five or six floor plans. It was the

training-wheels version of building a house. The plan Rita and Roy had selected was a three-bedroom ranch. They had moved

in in 1963, when Rita was twenty.

By then, they’d been married three years and already had two sons, Scott and Mark. Roy, who was six years older than Rita,

was embroiled in his work with the engineering firm of Garver and Garver. It was an exciting time to be an engineer. Little

Rock was being virtually encircled by the new interstate highway system, and Roy’s company was involved in a major study for

part of that. Roy and Rita, who had met and married in their little central Arkansas hometown of Russellville, felt that their

future was as limitless as that interstate highway now seemed to be. Rita had studied art for a while and then had switched

to engineering herself. Finally, she had dropped out of school to marry Roy. Now she was happy just being a mother and housewife.

After having lived in a succession of apartments, they even found their new house in the subdivision limitless at first. Then

Rita got pregnant again. In February 1966, she gave birth to a daughter, Lori. Scott was two and a half, Mark was one and

a half, and now they had a new baby. It was amazing how fast that house had shrunk. Rita started watching the want ads, circling

and clipping descriptions of houses that seemed promising. One day, she ran across an ad for a house at 501 Holly. It sounded

wonderful—a front porch, lots of bedrooms, wall-to-wall carpeting, a big corner lot. Not only that; there was no down payment

required—the buyer would just assume the loan. The house was for sale by the owners themselves. That night when Roy came

home from work, Rita had already made an appointment with the people, a Mr. and Mrs. Murphree.

Dropping the kids off with Rita’s aunt, Roy and Rita drove from the new subdivision into the old tree-lined streets of Hillcrest.

It was dark when they got to Holly Street, but the house lights glowed. In the blush of lamplight, the timeless dance ensued:

Rita was mesmerized, the way Ruth had been on

her

first day almost twenty years before. Roy and Rita never even saw this house in daylight before buying it. There are times

in your life when you don’t want to risk having your mind changed.

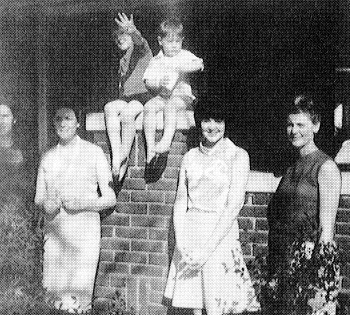

Rita Grimes, second from right, with her two sons and Roy's sisters. Rita loved 501 Holly no matter what calamity came along

.

They told themselves the house was in a spectacular location for a family with young children—the Pulaski Heights school,

offering nine grades in one location, was practically at their back doorstep. They told each other that no matter how hard

they looked, they wouldn’t do better. The Murphrees were asking $24,000. Roy got them to knock fifteen hundred dollars off

that. In the end, the Grimeses put $500 down and assumed the mortgage for $22,000.

That September of 1966, 501 Holly’s third owners moved in. But it’s part of the alchemy of houses that even when a man and

wife move into one together, they don’t necessarily move into the very same house. There’s a photograph of Rita, one of the

few snapshots of her taken here, and she’s standing in front of the house with three of Roy’s four sisters, plus Scott and

Mark, who’re perched upon one of the brick half columns, as though on a pedestal. Rita, in her bright yellow A-line and sixties

bouffant, is only twenty-four in this picture, but her deep-dimpled smile says she’s shed her cookie-cutter box in the subdivision

and slipped into a unique identity, an identity even older women would have to respect. Rita would love this house, the

idea

of it, the whole time they were here.

There are numerous snapshots of Roy at 501, and many of them catch him, naturally, with a smile on his face. But one picture

taken about the same time as the one of Rita captures what I now know to be the worry Roy felt about this place. He’s standing

in front of the house, with his arm around his mother, and just over his left shoulder is a tree I had never known existed.

He says it wasn’t much of a tree—it’d been struck by lightning or something, and the top was gone from it. As soon as Roy

saw it, he knew he would have to take it down eventually. At this house, even the

trees

needed work. Roy’s expression in this photo says

he

had left his new, small, easily managed house in the subdivision and slipped into maintenance quicksand. He would be weary

of it long before he would find a way to escape.

They took to calling the living and dining space “the bowling alley.” With the sudden absence of Ruth’s heavy Victorian furniture,

that sprawling expanse of beige carpet now looked incredibly empty. Rita and Roy had no dining room furniture at first, just

a dinette set for the kitchen. They placed their small white brocade sofa and a couple of velvet chairs in the living room

area, spreading an Oriental-style rug under the side-by-side cocktail tables. Rita arranged a few items—a picture, some sconces,

one of those big decorative keys that were popular then—over the mantel and positioned her family knickknacks in the otherwise-empty

bookcase by the fireplace. Still, it wasn’t exactly cozy. Every time they walked through the front door, they were met by

the ringing reminder that this was a

real

house, and they were neophytes.

They did have a piano, though, and a record player with an eight-track cassette deck. Rita put all of those music-related

pieces in the room off the living area, which was now officially the music room. The middle room, the one with all those bookcases,

became the den. That’s where the TV set was. Nineteen sixty-six was the year color television became the norm—the demand for

color sets was so great that you had to

wait

to get one because local stores would be out of stock for months at a time. Roy and Rita had just made the switch, buying

a big black Magnavox console model, which they placed in front of the bookcases. The years the Grimeses lived in this house

spanned the eras from

The Green Hornet

to

Kung Fu,

from

The Milton Berle Show

to

The Sonny and Cher Comedy Hour.

In the evenings, Roy and Rita would settle back in the old green Herculon chair or spread out across the floral-print sofa,

while the children sprawled on the floor in front of the TV, their chins in their hands.

The whole family slept upstairs. In the beginning, the two boys shared the big bedroom where Martha Murphree had walked on

doorknobs; in the smaller room adjacent, little Lori slumbered in her crib. Rita and Roy, who had a king-size bed, planned

to use the big attic room as their master suite. This room does have wonderful potential for that. It’s cozy; the ceiling

slopes on either side, evoking the romantic aura of a Parisian garret—especially at night, when the shadows from the big elm

brush across the walls. Back when the Murphrees had taken out the first pair of French doors downstairs, they’d knocked out

a couple of windows facing the front of the house and installed the French doors here. Now you could open those doors and

step out onto the roof of the front porch; in theory, it was like having your own terrace off the master bedroom.

Roy and Rita had big plans—they were eventually going to level the floor, and there was talk of building a bathroom in the

big storage closet just inside the door. To get them started, though, Roy covered the bare floor planks with rust-colored

linoleum designed to look like a basket-weave pattern of bricks. Thirty years later, that linoleum is still here. There’s

no bathroom. A marble still rolls to the wall.

Eventually, Roy and Rita traded rooms with the boys, giving them the attic and painting their old room a bold and cheery gold,

complemented by a red-and-gold bedspread and curtains, as well as by a bright red piece of carpet that captured the spirit

of their Spanish-style furniture. It hadn’t taken Rita long to decide the attic wasn’t for her. That first arrangement was

scrapped after a night when Roy was out of town and Rita was trying to drift off to sleep. Suddenly, a book on the bookshelf

fell over. Rita was petrified.

What was that noise?

She was afraid to scream, afraid to do anything. She lay there hugging her pillow all night long.

Old houses, with their creaks and groans and gothic shadows, do have a way of playing tricks on your mind. I once lay awake

for hours in our big old house in Hazlehurst, convinced that the hooded figure in the far corner was Death and that, although

I could see

him

plainly, I would never again see morning.

All these years later, Roy Grimes can still take a sheet of tattersall drafting paper and sketch out a precise portrait of

the malaise that had overtaken the den. He shows me how time, conspiring against joists in the damp darkness beneath the subfloor,

eventually succeeded in shifting bricks in full sunlight outside the window, allowing rain to invade the wall. It’s a lesson

of life, taught by a house: Everything is connected. Joists had rotted, the floor had dropped, and the brick had kicked up.

Roy spent a good portion of his first months at 501 Holly crawling on his knees beneath the den, propping up the joists with

concrete blocks, firming up the sagging floor as far to the north edge of the house as he could go—which wasn’t quite far

enough.

He takes out another piece of paper and draws one slanted line, representing the angle of the terrain sloping from right to

left—north to south. Then he draws a horizontal line, representing the subfloor of the house. The lines intersect at the far

right. He explains that this house was actually built into this hill, and the contractor didn’t excavate completely on the

north side. There’s no room to crawl under there—which means you may have no idea if something

else

is crawling under there. A man had to come out and jack up the corner of the house in order to reset the row of tipped brick.

The garage was obviously on its last legs. Roy was afraid to park his Mustang in it, but more than that, he was afraid for

his children’s safety. Young boys love to explore musty car sheds, where old tools hang from bared ribs and boxes of potential

treasure loom in the half-light. After six months of worrying, Roy came to a decision: The garage had to go. He hired a crew

of high school boys, who came over wielding sledgehammers and testosterone. They probably would’ve paid Roy to

let

them do the job, though he paid them two hundred dollars instead. When it was over, Roy had dirt hauled in to fill the void

where the garage had been. With that area built up to the slant of the rest of the backyard, he blocked off the driveway with

railroad ties and a section of fence. He did away with the wooden gate between the garage and the back sidewalk. Finally,

in the spot where Jessie Armour’s servant’s quarters had stood, he poured a slab of concrete and put up a white prefab metal

shed from Sears.

Had Rita been watching this process from the downstairs back bedroom, she would’ve been careful not to get too close to the

window, which was about to fall out. Obviously, there had been movement in the floor and wall, and the entire window frame

was now cocked out at the top. Roy had to jack the windows, horizontally, back into place. Then he went in like a surgeon

and reattached the frame to the wooden skeleton inside the wall.

Throughout the house, the story was always the same—the ravages of time, combined with carelessness or neglect. The infrastructure

was crumbling. Tile in the upstairs shower had been painted over and was peeling. There was some problem with the plaster

in the corner bedroom upstairs—wallpaper wouldn’t stick to it, and they papered that room three times in the seven years they

were here. The kitchen was covered in what Rita says was “cheap paneling”—even the cabinets were made out of it. There were

no built-ins, and the stove was twenty years old. Roy had a carpenter come in and redo the kitchen. The man added cabinets,

plus a new stove and dishwasher in that buttery seventies yellow. There’s a photograph obviously taken by Rita—it’s of her

family posed before the new stove and range. Somehow, the aim of the photographer has shifted slightly, so that Roy, Scott,

Mark, and Lori are off center to the left, sharing the spotlight with the sparkling new range top.