If These Walls Had Ears (32 page)

Read If These Walls Had Ears Online

Authors: James Morgan

The instructor watched, fascinated, for a moment, then came and stood over her pupil. “Boy,” she said to Sue, “you really

use that music

well

.”

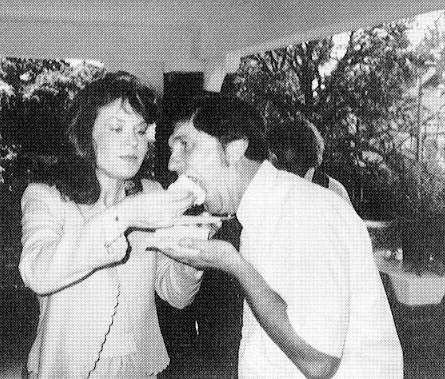

Donna and Fack Burney on their wedding day in September 1981

.

Burney

1981

1989

S

tudy one house over time, and it’ll tell you all you need to know of life and death, of dreams and disappointments, of vanity,

desperation, duplicity, denial.

Sue Wolfe remembers receiving a call from Sue Landers in the wee hours of the morning following the aborted closing. “She

was hysterical, shrieking. She said they’d found that termites had eaten out the entire floor and that it was going to cost

them seven thousand dollars to fix it. She said they thought we had cheated them.”

Sue Landers says this house was the beginning of the end for her marriage. She and Myke never actually laid eyes on the grave

site, which was just inches below the floor of the space that Sue had called her plant room. In hindsight, how appropriate,

all those potted plants marking the spot.

The damage wasn’t as extensive, or as costly, as Sue had first thought. But it was bad enough. I found a diagram of the problem

in the files of Adams Pest Control: The damage stretched across the front beneath the living room and along the side into

the den, but it looks as though the problem

centered

under that front room just off the living rooni—the room that had caused Billie Murphree so much worry about water, the room

in which Martha Murphree had seen the floor furnace float. Apparently, because of how the house was built into the hill, there

had never been enough room to get under that part to check adequately. For almost sixty years, time had been taking its silent

toll. And now that that substructure was known to be rotten, there wasn’t room to go under the house and do the work required.

So they had to tear out the floor from inside the room. Neighbors who peered through the windows during construction describe

the scene as though describing an open grave—a dark hole in the surface, surrounded by that which once had covered it and

soon would be put back in place, thankfully resealing the sight from human eyes.

The work took only a couple of days. The Landerses credited Jack Burney $3,800 for the repairs. The Wolfes discounted by two

thousand dollars the note they were holding for the Landerses. The closing was rescheduled for August 14. At the end of the

day, the Landerses—who, with Sue’s father’s help, had put down $20,000 on this house the year before—walked away with $8,334.93.

The repair work wasn’t begun until after the closing. Before it was started, much less finished, the Landerses were trying

to find someone to blame. When they finally took a good look at their termite contract from Adams Pest Control, they discovered

that, as with most insurance policies, it came with a caveat: “Note: Existing damage to front sill & joists, center sill &

joists, and left & rear sills and joists not to be replaced.” If they looked further, they might’ve found a letter sent from

Glynn Adams to Landmark Abstract/Title at the time they bought the house from the Wolfes:

May 6, 1980

Gentlemen:

You will please be informed that we have inspected the above-captioned property and are pleased to report to you that our

inspection revealed no evidence of active termites. However, there is evidence of past infestation and existing damage.

Our original treatment was performed on this structure April 20, 1973. The owners have maintained a Termite Protection Contract

on the structure since that time. The coverage is effective through April 20, 1981. Attached is our Termite Protection Contract

reflecting that the existing damage is excluded from coverage

.

It is evident that such areas as finished floors, studding, sheathing, interior trim and others could not be visibly inspected

for possible damage; therefore, all future claims or adjustments, if any, will he based on actual infestation at the time

damage is found

.

This letter is not to be considered a letter of clearance. It is merely a transfer of an existing Termite Protection Contract

which has an exclusion of existing damage.

Of course, there

wasn’t

actual infestation—just old, sad bones that’d returned to dust.

The Landerses hired an attorney, who contacted the Realtor with whom they’d worked when they bought the house. The Realtor,

whose company had since gone out of business, steadfastly denied any liability or responsibility for the “oversight” of allowing

the termite contract to be transferred, instead of requiring a standard letter of clearance. The attorney recommended filing

a complaint with the Arkansas Real Estate Commission; if that brought no relief, then they could sue the Realtor for damages.

Myke and Sue decided they’d had enough. They dropped the effort to find an external scapegoat and instead went on with their

lives.

I sometimes think of that gash in the floor in 1981 as the physical equivalent of Ruth Murphree’s emotional cave-in when Pat

eloped twenty-two years before. Each in its way marked the end of something and the start of something else. Not, as you’ll

see, that the problems with rot were entirely over. But the gash in Sue and Myke Landers’s plant room seemed to mark, literally

and finally, a bottoming out—a culmination of the long, painful slide that had been taking place since the end of the Murphree

years.

It had been a period during which existence of the house had overshadowed existence

in

it.

Now that’s changed. With Jack and Donna Burney, and later with Beth and me, this house has seen parties again—more, it seems,

than at any time since the Armour years. There’s another similarity, and probably you could make a connection between the

two. For both the Burneys and the Morgans, 501 Holly represented a new beginning—the first home of a newly blended family.

Shortly before Jack closed on this house, he brought his parents over to see it. The floor was buckled, of course, and the

place looked the way Jack has described it. His father wandered around, taking it all in. “Boy,” he finally told his son,

“I think you’ve bitten off a lot here.” Jack’s mother didn’t say a word the entire time.

A couple of weeks later, Jack went to see his parents. He sat them down and told them he had something to say. “I’m going

to get married again,” he said, “and I just wanted to let you know about it.” He gave them all the details about Donna, who

lived in Dallas but who would be coming to Little Rock the very next weekend. He promised to take her over to meet them.

Jack’s mother was beside herself. “Oh, Jackie,” she said, “I’m

so

happy. I was just so afraid you were going to buy that house arid move some girl in there and

live

with her.”

He did, for a few weeks. He and Donna wouldn’t marry until late September, but they had to move in at the beginning of the

month. They wanted to get the floor work going, but that wasn’t the main reason. The real reason was that Jack had a tradition

to uphold.

On the day in 1993 when I finally met Jack, I had a sense that I had known him somewhere before. I liked him, found him to

be an affable, easygoing sort of fellow. I could imagine having a beer with him. As he told stories about his time in this

house, I watched his face and listened to the way he talked— the way he tacked on the phrase “that type of deal” to other

things he was saying, such as in “I had eight people working for me, and that type of deal.” It was involuntary, a nervous

filler; or it was just good-old-boy imprecision.

That

type of deal. Then it came to me: Even at age fifty-eight, Jack Burney reminded me of several guys I’d known in college.

The aura of college surrounds Jack like— well, I was going to say like

ivy,

but that gives the wrong message. The aura Jack projects reads more like pep rallies, panty raids, frat cats, and beer busts.

He’s a product of the rah-rah fifties, before the world changed so, and he admits that in his mind he’s never really gotten

out of college. He went to the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. After he left that day, I thought of Updike’s Rabbit

Angstrom. Jack probably wouldn’t have been a basketball star, but he gives off a sense of having found the old days golden.

Until recently, he was president of the local Sigma Chi alumni group. He even looks the way I imagine Rabbit to look: the

boyish shock of hair gone to gray; the collegiate khakis and fraternity-boy blazers in a middle-age size.

No, the reason Jack had to be in this house early that September was because of his annual first game Razorback party.

He and Donna and her twelve-year-old daughter Andi moved in— without furniture—and slept upstairs on a mattress while saws

buzzed and clouds of dust filled the downstairs. The important things were the pigs. Jack has a collection of red concrete

razorback hogs, the Arkansas mascot, and he positioned them around the side. yard like garden ornaments from a Martha Stewart

nightmare. He set up his kegs and his buffet tables and that was it. He and Donna invited fifty couples. Jack and his guests

dressed in red and white and drew themselves a few cool ones, no doubt celebrating a new season not just for the Hogs but

for good old Jack— husband, homeowner, host.

An hour before game time, they flung open the French doors to the kitchen and the men simply picked up the tables, food and

all, and set them inside. Then as many as could fit piled into Jack’s car and rode the few blocks to the stadium, which was

designed by the same architect who had designed Jack’s house, and parked in Jack’s special close-in parking space before pouring

themselves out into the wider sea of red. After the game, they returned to 501 Holly and carried the groaning buffet tables

back out to the yard, and they picked up again right where they’d left off. Jack’s new neighbors could tell that a whole new

era had been ushered in. “Woooooooooooo PIG!” went the cheer that, time and again, pierced the soft fall night.

“Sooieee!”

Though the fifties tugged gently on Jack’s blazer sleeve, the life he and his family lived here strikes me as more representative

of their time than any family since the Murphrees. The Burneys were pure eighties. There were three reasons for that: one,

their work; two, their materialism; and three, their family.

Jack was then and still is a salesman. When he moved here, he and a partner owned a wholesale distributorship for appliances

and electronics. They had Gibson ranges and air conditioners, Sharp microwaves, televisions, and VCRs, plus various car radios

and stereos. They were the middlemen, selling to dealers throughout Arkansas, north Louisiana, and east Texas. The public

had a passion for the latest in electronics, and Jack reaped the profits from that passion. Meanwhile, Donna, who in Texas

had worked for a construction firm, found a good job as executive secretary to the comptroller of Fairfield Communities, a

company riding another eighties wave—time-sharing.

Their house reflected their taste and times. When I first walked through here, I remember thinking that I had never seen so

many television sets and sofas in one house in all my life. There was one of each in almost every room. A big-screen TV stood

right where Jessica Armour had lovingly placed her Empire sideboard; where her guests had dined at a table for twelve, the

Burneys lolled on a sectional sofa. In other words, they didn’t use their dining room

as

a dining room; it became instead a kind of shrine to the god of electronics, with the remote as a much-fingered rosary. The

downstairs back bedroom—our Geranium Room—was where they placed their dining room table.

I’m slightly surprised that Jack bought this house. I guess, after four years of his being single, it said

home

to him in a way that a new house in the suburbs couldn’t quite manage. Or maybe it was Donna who liked old houses. Her decorating

was certainly fussier than the family’s apparent lifestyle.