I'm Just Here for the Food (20 page)

Read I'm Just Here for the Food Online

Authors: Alton Brown

Tags: #General, #Courses & Dishes, #Cooking, #Cookery

Rate of transmission:

very high

Common transmitters:

liquid fats, such as canola, peanut, and safflower oils

Temperature range:

relatively narrow, between 250° and 375° F

Target food characteristics:

• small, uniform pieces of food containing high protein and/or starch content

• foods that can be dredged, breaded, or battered such as onion rings or fish strips

• firm vegetables

Non-culinary application:

fast-food french fries

Batter Up

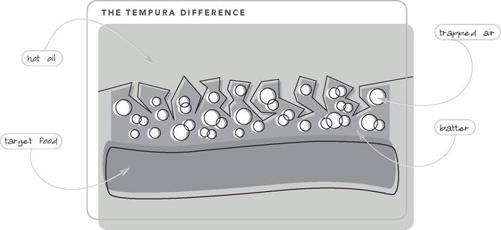

A batter is basically a liquid version of a standard breading, or at least the first two parts of it, liquid and starch. For my money, the best batters emulate the Portuguese-Japanese hybrid style of frying called tempura. Such batters create an almost impossibly thin and light coating that is like wrapping a present in tissue paper: you can literally see through it. This is my basic batter recipe, although I do also use a beer-based batter for fish and chips and occasionally chicken fingers (you know … for the kids).

Steer clear of the blender versions of this recipe, which produce thin, overworked batter. Also, since tempura is Asian, you’ll probably serve it with some sort of salty soy or ponzu sauce, so you don’t want to oversalt the batter.

Application: Immersion-Frying

Heat the oil to 350° F.

In a small bowl, sift together the salt, pepper, and cornstarch. In a medium bowl, whip the egg whites until soft peaks are formed. Continue whipping while gradually adding the cornstarch mixture.

Holding the target food at the end with tongs, quickly wave the food through the batter (this type of frying is best done one piece at a time), retrieve from the batter, let it drip for a few seconds, then put it into the oil.

Using the tongs, press the food down to keep it completely submerged in the oil (to prevent the food from flipping over—if an air bubble forms on the top between the food and the batter, it will just keep rolling over). When the food has turned golden brown, approximately 3 to 5 minutes, remove the food to the draining rig. Repeat with remaining target food and serve immediately.

Notes:

Previously used oil works better than fresh for this recipe. If you use fresh oil, the target food will be done before the batter has turned golden brown.

Possible target foods include: butterflied shrimp (split them down the middle, but not far enough to split them in half; you can also leave the tails on to allow an unbattered “handle”), and blanched vegetables, such as sliced sweet potatoes, broccoli, squash, and flat-leaf parsley. This recipe makes enough batter to coat about ½ pound of U21/25 shrimp, a medium-sized head of broccoli cut into florets, and one large sweet potato, thinly sliced.

Software:

2 quarts peanut or safflower oil

(see

Notes

)

Salt

Freshly ground white pepper

¾ cup cornstarch

1 cup egg whites

Target food (see

Notes

)

Hardware:

Electric fryer or heavy Dutch

oven fitted with a fat/candy

thermometer

Small mixing bowl

Mesh strainer for sifting

Medium mixing bowl

Electric mixer

Tongs

Draining rig (see

illustration

)

PONZU

Ponzu sauce is Japanese and is typically made with lemon juice or rice vinegar, soy sauce, mirin or sake, seaweed, and dried bonito flakes. Bonito flakes, also called katsuobushi, are made of strongly flavored tuna.

Fats for Cooking

Fat is one of the body’s basic nutrients. According to Harold McGee in his

On Food and Cooking

, fats account for about 10 percent of daily caloric intake in developing countries, while in affluent societies like our own the figure is more like 40 percent.

As consumers, we became saturated with fat talk years ago when doctors decided that fat was bad. Since Americans have been steadily plumping up for the last few decades, this wasn’t a great leap of quantum thinking. But then somebody figured out that different fats elicit different responses in the body, depending on their saturation. Thus began the great dialogue and even greater confusion regarding the nature of saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fats. As for cholesterol, well, let’s just say that the amount of cholesterol in the foods we consume is not necessarily reflected in the amount of serum cholesterol in our bloodstream. But, just in case you’ve been buying one particular brand of vegetable oil simply because the container proudly proclaims it “cholesterol free,” you can feel safe and secure in knowing that it’s true. Of course, there’s no such thing as a vegetable oil containing cholesterol. Only animal products, such as lard, contain cholesterol.

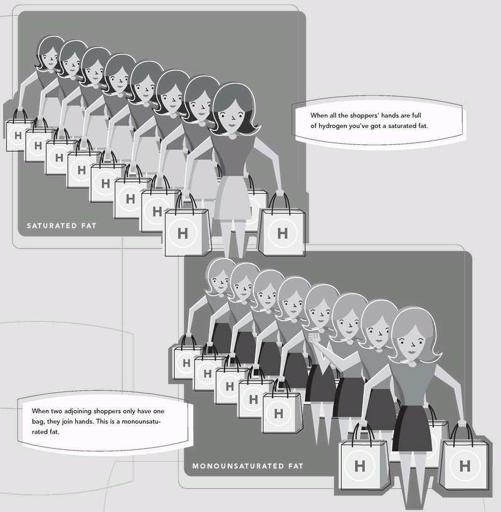

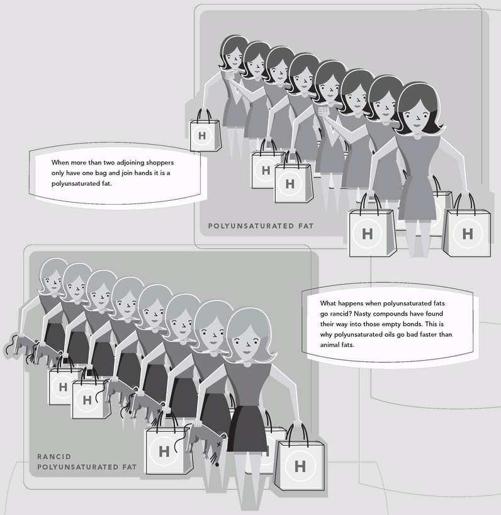

All culinary fats are called triglycerides. The term refers to the fats’ molecular architecture, comprising three fatty acids that are esterified, or hitched, to a glycerine molecule. The structure of these fatty acids greatly determines how the fat is going to act when it gets into the culinary (and biological) food chain. Although there are a lot of different fatty acids (a whole lot actually), they all fall into one of three categories: saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated.

A fatty acid is basically a long chain of carbon atoms. Besides being anchored to the carbon in front as well as behind, each carbon has two chemical arms that can each hold a hydrogen atom. When all the carbons in a chain have their hands full of hydrogen, it is saturated, meaning that it can hold no more. Fats high in this kind of fat tend to be solid at room temperature, and they make cardiologists nervous.

If two adjoining carbons on a chain are lacking a hydrogen (this always happens in twos; there are never singles or threesomes), they join hands, creating a double bond.

FRY VESSELS

Until recently I did all my frying on the cook top in a big Dutch oven. I still fry french fries there because I use a two-pass method, which requires a pass at 300° F, then another at 350° F. That said, I recently came into possession of an electric fryer and I have to say, I like it.

I’m not talking about one of those fancy Italian numbers with the hinged lid and the “cool touch” chassis. This thing looks like a dark metal bucket with a cord coming out of the base. It’s called a “Dual Daddy” and it’s nice and wide but still deeper than wide, which is good. And get this: no thermostat. It shoots for about 380° F, then waits like a dog by the door. You put in the food, and unless you really overload it you’ll never see the underside of 320° F. I’ve learned this with the help of a fat/candy thermometer, which comfortably fits on the side of the fryer. I never add food until the oil has reached its full 380° F and I never put in enough food to cause the oil to drop below 320° F.

Using this device, I have gotten the cost of cooking a large bag’s worth of potato chips down to approximately 22 cents. The only craft to using this device is knowing how much food to put in at one time. This simple frying device comes with a big snap-on plastic lid; the implication is that you store your cooking oil in the device itself, but this is not a good idea since the more oil/air air contact you have the faster the oil will oxidize and go rancid.

If this occurs just once on a chain, the fatty acid is referred to as monounsaturated, meaning that there is a vacancy, but only one. If there are more vacancies along the chain, it is polyunsaturated.

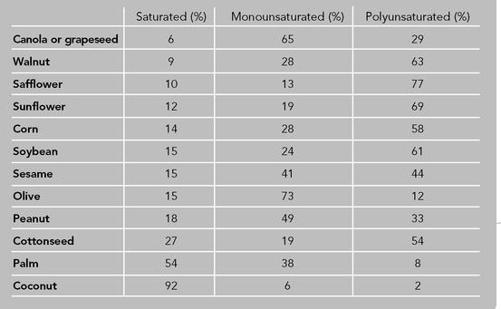

All fats contain all three types of fatty acids. What decides how a fat is to be classified depends on how many of each kind there are (see

illustration

).

Folks in lab coats are still duking out whether mono- or polyunsaturates are better for us. Culinarily speaking, things are a little more cut and dry. But there are still choices and trade-offs.

FRYING: THE WRAPAROUND PAN

Frying works so well because it conducts high heat to the entire surface of whatever it is you’re cooking. It’s as if you had a pan that could wrap itself around the food. And when done right, very little of the fat is actually absorbed into the food being fried. The trick is to choose your fat wisely.

Fat Saturations

Fats high in saturated fatty acids create wonderfully crisp fried foods, but saturated fats have relatively

low smoke points

so you don’t get much use out of them and they’re not very good for you. Saturated fats come from animal sources and can hold their shape at room temperature. The most commonly used saturated fats are butter, lard, and suet.

FAT FACTS

•

All oils are fats, but not all fats are oils.

•

If a fat comes from an animal, it’s considered a fat. If it’s a liquid at room temperature, it’s considered an oil.

•

All animal fats are solid at room temperature, which is why we say “chicken fat” rather than “chicken oil.”