I'm Just Here for the Food (8 page)

Read I'm Just Here for the Food Online

Authors: Alton Brown

Tags: #General, #Courses & Dishes, #Cooking, #Cookery

You see, most of the grilling in this country is performed by men, and men like fire. In fact, I suspect that the backyard cooking boom this country witnessed in the late 1940s and 50s was really about playing with lighter fluid. It’s not our fault, of course. I trust that someday the lab-coaters will have identified a gene, unique to the Y chromosome, that will be dubbed the “firestarter gene.”

Whether it’s for the love of fire or food, grilling is more popular today than ever before

8

despite the rise in concerns over potentially cancer-causing compounds in the smoke created when animal fats burn.

FUEL MATTERS

The average hardwood log contains around 39 percent cellulose, 35 percent hemicellulose, 19.5 percent lignin, and 3 percent extractives and such. When you burn it—well, I shouldn’t say “burn,” because wood doesn’t actually burn—it undergoes a kind of thermal degradation known as pyrolysis.

9

During this process, the wood beaks down into a slew of volatile substances (carbon monoxide and dioxide, hydrocarbons, hydrogen, aldehydes, ketones, alcohols, tar, phenols, that sort of thing) and a solid carbon mass. When you see flames and smoke, that’s the volatiles burning. When those are exhausted, what’s left of the wood glows. These are called coals, and they burn much hotter and much cleaner than the stuff that fueled the flames. They are also the stuff of which all good grill sessions are made.

Charcoal is nothing more than wood that has had its volatile components removed. Although it’s a lot more complicated than it sounds, commercial charcoal is made by heating wood (or in the case of briquettes, wood chips) to about 1000° F in an airless environment. Natural lump charcoal is fired with grain alcohol; most briquette makers opt for petroleum. This cooking removes those volatile components while leaving the carbonaceous mass intact. After cooling, the lump charcoal is bagged and shipped. Chips get mixed up with lime, cornstarch, and other binders and are compressed into briquettes. This is not to say that all briquettes are bad. “Natural” briquettes still contain binders like cornstarch but they lack the nitrates and petroleum, and the non-burning filler (sand) you find in standard briquettes. Natural briquettes burn longer than lump or chunk charcoal, which lights faster and burns a good deal hotter. Consider using a mixture of the two fuels in certain situations. If you’re interested in smoking foods, remember that chunk charcoal and charcoal briquettes are processed products that burn to produce hot coals but do not alone have the ability to transport flavor via smoke. Adding wood chips or chunks is necessary to produce the smoke that flavors food.

LIGHT MY FIRE

Although natural charcoal fires up far easier than briquettes, charcoal is still just lumps of carbon, and lumps of carbon aren’t exactly fireworks. Clever hairless monkeys that we are, we’ve come up with a wide range of devices designed to speed lighting. Only one of these am I wholeheartedly opposed to: fast-lighting briquettes. I’m not naming names, but you know what I’m talking about. It’s not that I’m afraid that one of these chemical-laden lumps is going to just go off in my hand, it’s just that no matter how far I burn them down before I put the food on the grill, I can swear I taste something … funny. That’s all I’m going to say … funny.

A BARBECUE BY ANY OTHER NAME

Folks like to argue about what defines great barbecue. What they really should be arguing about is what the word actually means. It is just about the only word that out-connotes roast. You could, for instance, say, “I fired up my barbecue and barbecued a mess of barbecue for the church barbecue.” (Try that out on a French cook someday—it’ll crack him like an

oeuf.

)

The origins of the word are traceable. When Columbus landed on Hispaniola, he found the natives smoking meat and fish on green wood lattices built over smoldering bone coals. The natives called this way of cooking

boucan

. The Spaniards, being good colonialists, decided to change it to

barbacoa

. On his next journey from Spain, Columbus brought pigs to Hispaniola. A few of them got away, and soon there was more

boucan

than you could shake a flaming femur at. As word got around that the get-tin’ was good on Hispaniola, bandits, pirates, escaped prisoners, and runaway slaves made for the island and lived high on

boucan

three times a day. The French, witty as they are, called these individuals

boucaniers

.

So, the folks in Tampa have a football team whose name means “those who cook over sticks.”

As far as modern usage goes, barbecue the noun refers to slow-cooked pork or beef. Barbecued chicken is grilled chicken served with barbecue sauce. Barbecuing is the act of making barbecue; cooking directly over coals is grilling.

A NOTE ON SMOKE-MAKING ELEMENTS

I’ve received angry letters for saying this, but gosh darnit I’m saying it again anyway: unless the food in question is going to be exposed to smoke for several hours, what kind of smoke it is just doesn’t matter as long as it’s from a hardwood. If you’d like to add smoke to your grill-roasting experience I suggest piling half a cup of hardwood sawdust in the middle of a 10-inch square of heavy-duty aluminum foil. Bring all four corners together and twist the pack so that it looks like a metal comet with a short tail. Poke the head of the pouch with a skewer a couple of times and you’ve got a grill-ready smoke bomb.

YOU WANT CHAR? I’LL SHOW YOU CHAR

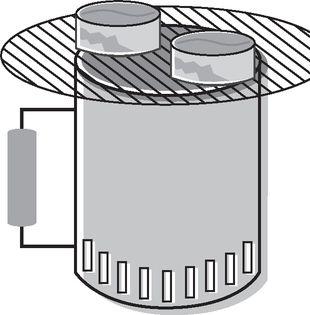

When you want serious firepower, place a small grate (the cooking grate from a Smokey Joe is perfect) directly on your chimney. This is like cooking over an upturned F-16. It’s not suitable for everything, but I’ll sometimes do little hunks of prime tuna as a stand-around-the-grill appetizer.

Lighter fluid may be the perennial pyro-preference, but there are other firestarter options. My favorites are electric-coil starters and chimney starters. The first requires 110 volts of power and a safe place to set it down once you’ve removed it from the grill, but it does the job quickly and effectively. A chimney starter is also fast and it allows you to have lit coals standing by at all times. A chimney does, however, require a safe place to live. I keep mine on a cinder block (but never on gravel).

During a multiday grilling binge last summer I padded out to my extremely carbonaceous carport to fire up one of the three grills that always seem to be there. I loaded a chimney with chunks and reached for some newspaper to stick in the bottom. But the only paper I could scrounge was a big wad of paper towel I’d used to wipe down grill number two the night before. So I used it. Fifteen minutes later the paper towel was still burning. Of course: I’d rubbed down grill number two with a bit of vegetable oil, essentially making the wick for an oil lamp. I was delighted with this discovery despite the fact that the rest of mankind had figured it out a few hundred thousand years ago.

To make a long story short, now I lay a sheet of newspaper on the ground, mist it with vegetable oil, wad it up, and stick it under my grill’s charcoal grate. I pile on the charcoal, then light the paper through one of the air vents with my pocket torch. It never, ever fails—or at least it hasn’t yet.

I still keep a couple of chimney starters around for those times I need to have some charcoal lit before adding it to the fire or have a filet or hunk of tuna to sear (see illustration, left). Other than that, I’ve gone to the oil-on-paper method, which is a lot cleaner and a lot less dangerous.

10

The Grill

There was a time when I did not own a gas grill. It is not that I had anything against natural gas as a fuel (even if it does burn a little wet), it’s just that the only gas grills I’d seen that are worth a darn cost more than my first three cars put together. Gas grilling is really just upside-down broiling and the only major advantage that this kind of cooking has over oven broiling (assuming, of course, that you have a gas broiler) is that the grill will produce nice grill mark—but if you use the right pan under the broiler you can do that, too (see

How to Make People Think You Grilled When You Didn’t

). If you only have an electric broiler, a gas grill makes some sense.

And, as of 2002, I own a Weber Genesis Silver gas grill, which I love. No, it’s not ever going to give me the flavor of charcoal, but for speed and convenience it can’t be beat. This is not to say that I’ve gotten rid of old fireball.

Up until the late nineteenth century, rural communities would get together to build a charcoal kiln, a giant “teepee” of wood with an airshaft down the middle. The structure was covered with a kind of adobe made by mixing ash with mud and water. Once this covering had dried, a fire was set in the center shaft and the mouth sealed. Holes were opened at the base of the kiln so that the fire would have just enough air to cook the volatile elements out of the wood, leaving a carbonaceous mass behind. After a few weeks the kiln was torn down and

voilà!:

charcoal for everyone in the family.

A WORD ON COUNTER-TOP GRILLS

A certain retired boxer has made approximately a gazillion dollars by marketing an electric counter-top grill. I know plenty of folks who like them, but I’ve never been able to get any real lasting heat out of one. And without real heat there will be little if any sear. And, of course, with the top down there’s going to be steam. Don’t get me wrong, it’s a valid method of cooking—it’s just not grilling, and you should adjust your expectations accordingly.

I have learned that the George Foreman Grill has changed the world in a very positive way. Many people out there live without kitchens and this appliance gives many of those folks a way to cook that they haven’t had before.

I am very much at home with charcoal. I love charcoal. I can reach a Zen-like oneness with the coals. A couple of summers ago I constructed a 4-by-8-foot fire pit in my backyard and had special grates made to fit it. I cooked whole pigs over hickory fires, then harvested the leftover charcoal to use in my three grills. I am a freak, but I can live with that.

By the way, even truly fine gas grills cannot generate the heat of natural chunk charcoal. That’s because a glowing coal simply has so much of the light spectrum going for it. Don’t believe me? Go into a darkened hangar with a gas grill and a charcoal grill. Fire them both up and observe them through your infrared goggles. See what I mean?

CHARCOAL LORE

Henry Ford was really into camping. The Ford archives are lined with photos of the godfather of the assembly line lined up with his cronies, all sitting around smoldering campfires in suits and morning coats and ascots and spats and things. (I’d love to spend more time camping but I just don’t have the right cufflinks.) One is always struck by how puny the fire looks compared to the assemblage and their mansion-tents. Turns out that campfire starting and management was always an issue among the gents, who no doubt resented snagging their watch chains on kindling.

Now it just so happens that during this time Ford’s company was manufacturing an automobile called the Model A, and it was a ragtop. When engaged, the fabric top was held in place by wooden staves. The factory that made these staves had a lot of leftover wood chips to get rid of. One of Henry’s buddies started thinking about the chip problem and the campfire problem and in a true flash of genius conceived the charcoal briquette. The fellow’s name was Kingsford. Up until the 1950s, you could only buy Kingsford charcoal (boxed not bagged) from Ford dealerships. To this day, Kingsford charcoal controls 50 percent of the country’s charcoal market.

Grilling

When Brillat-Savarin made his famous remark “We can learn to cook but must be born to roast,” he was actually talking about the process we know as grilling, the cooking of foods (especially meats) via the radiant energy and convection heat generated by glowing coals or an actual fire. B-Savarin was right inasmuch as grilling cannot be taught; it can, however, be learned through experience. In other words, the only way to learn to grill is to grill.

Many people do not want to hear this. They want a recipe to follow, which is why there are so many books about grilling published each year. The problem, of course, is that besides the usual considerations that go into the cooking of a given food, there are many other factors unique to grilling. Among them: