I'm Just Here for the Food (30 page)

Read I'm Just Here for the Food Online

Authors: Alton Brown

Tags: #General, #Courses & Dishes, #Cooking, #Cookery

Steamed Cauliflower and Broccoli

Sounds weird, looks a little odd, but boy is it delicious.

Application: Steaming

Place a collapsible steamer basket in a large pot. Add water almost to the bottom of the basket. Bring to a boil, then add the egg to the basket, cover with a tight-fitting lid, and steam for 6 minutes.

Add the vegetables to the basket and steam for another 6 minutes.

Using tongs, remove the egg to a bowl of ice water. With fireproof gloves, grab the center rod of the steamer basket (they all have one, though for the life of me I can’t figure out why) and remove it to the counter with the vegetables still on board.

Peel the egg and shred it through the fine side of a box grater.

Heat the sauté pan over medium heat, then add 1 tablespoon of the butter. When the foaming subsides, toss in ⅓ of the bread crumbs and ⅓ of the grated egg then salt and pepper to taste. Stir until the crumbs begin to brown, then add ⅓ of the florets. Stir to coat, then transfer to a plate. Repeat with the remaining ingredients, making 2 more batches.

Why cook this in stages? Crowding the pan will mean more stirring, which can break the vegetables apart—and that would be bad.

Yield: 6 side servings

Software:

1 egg

½ head cauliflower, cut into florets

1 head broccoli, cut into florets

3 tablespoons butter

½ cup panko (Japanese bread

crumbs)

Kosher salt

Freshly ground black pepper

Hardware:

Steamer basket

Large pot with lid

Tongs

Fireproof gloves

Box grater

Sauté pan

Sweet Onion Custard

For more about custards and eggs, see the

Eggs-cetera

section.

Application: Steam

In a mixing bowl, whisk together the eggs, stock, and vinegar. Season with salt and white pepper. Divide the onions evenly among 4 ramekins and pour in the egg mixture to fill. Cover tightly with plastic wrap and then aluminum foil and set the ramekins in a steamer basket. Place steamer over a large pot of water at a low boil and gently steam for 12 to 15 minutes until custard is set but not firm. Serve hot.

Yield: 4 servings

Note:

Onions will reduce by half as you caramelize them, so begin with 1 cup of thinly sliced onions. Place a pan over medium heat and add 1 tablespoon of butter per onion. When the butter has melted, toss the onions to coat. Cook, stirring occasionally, until they are brown and soft.

Software:

3 eggs

1¼ cups chicken stock

1 teaspoon balsamic vinegar

Kosher salt

Freshly ground white pepper

½ cup caramelized onions

(see

Note

)

Hardware:

Mixing bowl

Whisk

4 ramekins

Plastic wrap

Aluminum foil

Steamer basket

Large pot

Ramen Radiator

This is the coolest dish in the book, which is not to say that you shouldn’t try the rest of the recipes. I just think this dish delivers huge dividends on a very meager investment.

Application: Steam

Preheat the oven to 400° F. Heat a sauté pan over high heat, add the oils, then add the mushrooms and toss; cook until caramelized, about 3 to 4 minutes. Transfer to a plate and set aside. Break the “loaf ” of noodles into 2 equal parts. Season the fish with salt and white pepper, spread a little honey on each filet, and sprinkle with chili flakes. Line the serving bowls with aluminum foil, making sure there is a lot hanging over the edges. Lay one half-loaf of noodles in each bowl and top with the fish. Spread the shrimp, mushrooms, and onions around the bottom. Top with the scallions. Pull the foil up around the food and crimp it to seal, leaving one tiny opening in each pouch. Mix the liquids together and pour half into each pouch and then seal. Set the pouches on a baking sheet and place in the oven for 22 to 25 minutes. Set the pouches back in the bowls and open at the table. A delicious aroma will fill the air as the steam escapes. Serve with chopsticks and a spoon to eat the “soup.”

Yield: 2 servings

Software:

1 teaspoon olive oil

1 teaspoon sesame oil

8 ounces brown mushrooms, sliced

(preferably cremini or shiitake,

but not button)

1 (3-ounce) package ramen noodles

2 (8-ounce) halibut or other mild

white-fish filets (salmon also

works well)

Kosher salt

Freshly ground white pepper

1 tablespoon honey

Pinch of chili flakes

6 medium shrimp, peeled and

deveined

½ Vidalia onion, sliced Lyonnaise-style

4 scallions, sliced on a bias

2 tablespoons soy sauce

¼ cup mirin (sweet rice wine)

2 cups miso or vegetable stock (if

using miso, the measurement is

2 teaspoons miso paste for 2

cups water)

Hardware:

Sauté pan

2 large serving bowls

Aluminum foil

Baking sheet

CHAPTER 6

Braising

Proof positive that dry and wet heat can get along in the same recipe.

Amazing Braise

Braising and stewing are compound methods that begin with searing or pan-frying and finish with simmering, and as far as I’m concerned, braises and stews are the finest edibles on earth.

They’ve got it all: caramelized crusts, tender interiors, and of course . . . sauce.

A braised dish typically contains either a large piece of meat or smaller pieces that are left whole. Pot roast is typically a braise, as is

osso buco

(braised veal or lamb shanks). The meat is seared in a hot pan to brown the exterior, then cold liquid is added (along with vegetables or other bits and pieces), the vessel is covered, and the dish is simmered for as long as it takes for the collagen in the meat to dissolve into gelatin. In a stew the meat is usually cut into bite-size chunks, which are sometimes dusted with flour, seared, then just covered with a flavorful liquid. A stew is as much about the liquid as the meat.

(Besides beef stew, consider beef Stroganoff, blanquette of veal, and chili.)

COLLAGEN AND GELATIN

Animal muscle is composed of bunches of meat fibers held together by connective tissue. Cuts of meat from parts of animals that don’t do much work don’t have a lot of connective tissue, but parts that either work a lot or have a lot of bone, do. However, not all connective tissue is created equal. See, some of the tissues don’t do much but shrink up and get chewy when they meet heat—we can refer to those as gristle. But others are coated in a protein collagen, and under the right circumstances collagen dissolves into gelatin, the stuff that brings body to homemade stocks and helps your family’s favorite gelatin mold set.

Note that this transformation of collagen to gelatin takes time. In fact, to do it right takes a lot of time. (That is, unless you swap hours on the clock for pressure; for more on

pressure cookers

.) How does this magical change happen, you ask? Gelatin is obtained by the hydrolysis of collagen, a process that is catalyzed by enzymes called collagenases. It all has to do with a slow, low, moist, covered cooking method. Taking the slow and low approach allows for increased conversion of collagen to gelatin and reduces the chance of over-coagulated muscle fibers. Upon cooling, the gelatinized protein partially resets, and can hold added moisture, resulting in a meat that is moist and flavorful.

The problem with most braising and stewing recipes is that they call for too much of a weak thing—liquid. Meat, like most living tissue, is mostly water, a good bit of which is wrung out of the meat during the long cooking necessary to render the meat tender. That liquid leaches out, and unless the liquid added by the cook is very concentrated, the result is a very weak sauce.

24

The key is to start with a flavorful liquid, reduce it, then let the meat liquids reconstitute it. Start with a quart of liquid, reduce it to a pint, and you’ll have a quart of rich sauce at the end of cooking.

The braising of tough cuts of meat reminds me of an old saying that one hears quite a bit in the film business: You can have it fast, you can have it cheap, you can have it good. Choose any two.

The catch-22 of braising and stewing is that when it comes to tough cuts like chuck, brisket, ribs, and shanks, you can’t have moist and tender. It’s simply impossible. Here’s why.

The metamorphosis of collagen to gelatin requires moisture, time, and heat. Since there’s already a good bit of moisture in meat, the amount we need to add is relatively low. The heat required however (a minimum of 140° F, but most often at temperatures close to boiling), would certainly qualify as well done in anything other than the darkest meat of poultry. That’s because as meat heats up, the individual muscle bundles tighten up like fists around wet sponges. The meat literally wrings itself out into the pan where it either waters down whatever flavorful liquid has been introduced or evaporates. That means that by the time the collagen conversion is just cranking up, a significant portion of the meat’s juice is in motion. And since several hours can pass before the process is complete, we can only deduce that tender meat is dry meat. Sounds logical, but how is it that braises and stews are some of the most lip-smackin’ foods known to man?

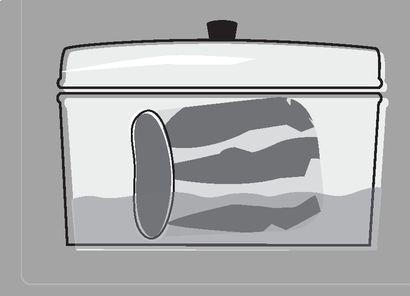

Despite the fact that there is very little liquid, the vessel is covered and the heat is low (we assume). This is not braising because too little of the food is in contact with the liquid.

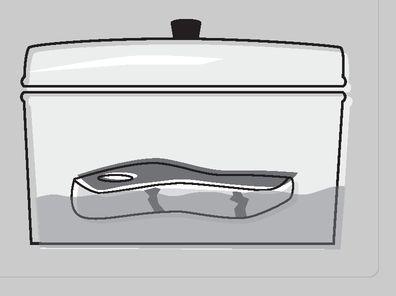

Since more of the food is in contact with the liquid this could be considered braising, but since only half the food is in direct contact, it isn’t very effective.

For one thing, if you cook most meats long enough in a wet environment, they will eventually relax, and just like a sponge, they’ll reabsorb some liquid, but not nearly enough to feel moist in the mouth. The real trick is to capture two other liquids in the meat: melted fat and dissolved gelatin.