I'm Just Here for the Food (46 page)

Read I'm Just Here for the Food Online

Authors: Alton Brown

Tags: #General, #Courses & Dishes, #Cooking, #Cookery

•

To chop is to cut food more coarsely than a mince.

•

To dice is to cut food into tiny cubes, approximately

⅛- to ¼-inch square.

•

To cube is to cut food into

½

-inch square pieces.

•

To julienne is to cut food into match-stick-thin strips, about ⅛-inch square, of various lengths.

•

Chiffonade is from the French for “made of rags” and refers to food cut into very thin strips (see illustration).

•

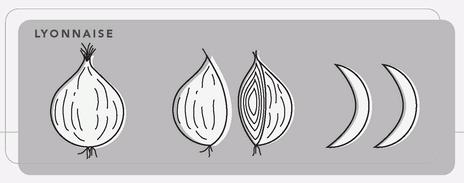

Lyonnaise-style is in the manner of the city of Lyons, France. Onions sliced Lyonnaise-style are cut lengthwise from top to root, rather than across (see illustration).

Storage

Deciding where and how to store a knife is a big deal to both the blade and your fingers. I like magnetic bars because they don’t take up a lot of space and if there’s any moisture left on a knife it will air-dry, but these are not usually recommended if you’ve got kids, pets, or homicidal tendencies. Storing knives in a drawer is fine as long as the drawer in question contains some device that will keep the blades separate and stable. Counter blocks are okay, but they rarely match up to an eclectic collection, and they tend to take up a lot of space. The best idea I’ve seen lately is a long skinny slot cut into the top of a butcher block deep enough for the knives to simply line up along the slot. Whatever device you choose, please make sure that the blades are completely enclosed. A friend had a rolling kitchen cart with a knife block attached to the side. One day he purchased a 12-inch slicer and put it into the block. Later that same day he reached down to the bottom of the cart for a pot, only to realize that the block was 11 inches long and had a completely open bottom. He had time to ponder this fact later as he sat in the emergency room.

Pots and Pans

Sometime during the last twenty years of the past century, the kitchen became the new living room. Not so much because cooking and eating are communal acts connecting us all via the collective rumblies in our tumblies, but because there was a lot of cash floating around and a plethora of expensive new kitchen pretties to spend it on. Suddenly kitchens that had never witnessed an egg boil were being fitted with five-thousand-dollar cook tops. And of course nothing befits a five-thousand-dollar cook top quite like a halo of silently shining geosynchronous sauce pans. Even I, with my two-hundred-dollar cook top, fell victim to pot-rack fever. Following several years of collecting I finally had to mount flying buttresses on my humble ranch house just to support the ceiling joists, which moaned at the butter melters, fry pans, sauce pans, sauté pans, Windsor pans, casseroles, stock pots, and griddles I had accumulated. Then came the day I dropped two C notes on a French potato pot. My family got together and applied some tough love, slipping in while I was at Williams-Sonoma and taking it all away, leaving me with nothing but my great-grandmother’s 12-inch cast-iron skillet. Some might call such intervention harsh, but once I quit my sobbing I found that I was free, finally, to cook. Really cook. My family slowly returned my pots and pans to me as Christmas and birthday presents, but in my new-found Zen-lightenment I gave most of them away. To this day, my rack remains light. Here’s the breakdown in order of importance.

12-Inch Cast-Iron Skillet

I recently got into one of those “What pan would you want if you were stuck on a deserted island” conversations you hear so much about. My 12-inch Lodge was the easy choice. Besides all the metallurgical and thermal reasons given in the Searing section, this remains a culinary chameleon. Not only is its shape versatile, the properly cured surface is hard and black and slippery as a newt in Vaseline.

37

I’ve even turned mine upside down and used the bottom as a griddle—oh yes, I have. I’ve used it as a flame-tamer, too, by placing other pans on top of it. I’ve baked biscuits in it, baked quiche in it, baked apple pie in it, I’ve cooked on campfires with it, and one particularly rough winter during my college years I managed to rip a gas heater off the wall, set it up on coffee cans, and fry bacon-wrapped prawns over it. Take care of that cast-iron skillet and it will never let you down.

What it’s good for: this would take too long. What it’s not good for: boiling pasta—that’s about it.

Cooking was the only way I could get dates during college.

5-Quart Casserole

This is a relative newcomer to my collection, but it easily replaces three different vessels in my life, thus allowing for more downscaling. It is essentially a small, heavy stock pot with two loop handles. Since I like finishing things in the oven I’ve never been much of a sauce-pan fan—I don’t like wrestling with straight single handles, which I think are pretty darned dangerous. Although this isn’t a common piece, several companies make one (or something close). Mine was made by All-Clad, the Smith & Wesson of the pot-and-pan world, if you ask me. It costs more than just about anything out there, but you’ll only have to buy it once, and since the pieces are so darned versatile you don’t have to buy many.

What it’s good for: a multitude of cook-top or oven applications, from soup beans to small batches of pasta, and steaming. What it’s not good for: sautéing; pan-frying.

8-Inch Teflon-Coated Fry Pan

I like eggs and this is my egg pan. It cost me twelve bucks. I keep it wrapped in a couple of layers of plastic wrap when I’m not using it so that its surface won’t scratch.

What it’s good for: frying eggs; scrambling eggs; omelets. What it’s not good for: sautéing, searing, or pan-frying.

3-Quart Saucier with Lid

In the deserted-island scenario, this one ran a close second to the cast iron. It’s a hybrid pan, half skillet, half sauce pan and the design is perfect for reducing sauces that pool in the small-diameter bottom. (It’s not called a saucier for nothing.) Its rounded bottom makes it perfect for roux-based sauces because there are no corners that a whisk can’t get into.

What it’s good for: all sauces from sawmill gravy to crème anglaise; reducing; rice (pilaf); simmering. What it’s not good for: pan-frying; sautéing.

12-Inch Sauté Pan with Lid

The main difference between a sauté pan and a skillet is the angle of the walls, which flare out on a skillet or fry pan and are straight on a sauté pan, thus granting you more flat floor space to work. Another important feature of the sauté pan is the loop handle on the side opposite the straight handle—very convenient for moving the pan in and out of the oven. My sauté pan is also a clad piece with an exterior of stainless steel over an aluminum core. This is my pan-fry and pan-braise tool of choice.

What it’s good for: chicken piccata; salisbury steak; fried green tomatoes; pan-frying in general.

38

What it’s not good for: stir-frys; thin soups; eggs.

Dutch Oven

Another cast-iron number. Heavy but the best vessel around for slow cooking. It’s got a wire loop handle for easy moving (or suspending over campfires, open hearths, and so on. Since it’s so gosh-darned dense, it holds heat forever; if I’m taking a hot dish to someone’s house, I’ll take it in the Dutch oven even if I didn’t cook it in there. (It never turns over in the car, either, which is a nice bonus.)

39

What it’s good for: long-cooking stews; baked beans; pot roast. What it’s not good for: sautéing.

10-Inch Stainless-Steel Fry Pan

Another clad pan, like the sauté pan, but this one has sloping walls that allow for single-handed food turning via the “toss.”

What it’s good for: sautéing. What it’s not so good for: eggs (they stick); pan braises (there’s not enough flat floor space); soup (it’s too shallow).

8 - to 12-Quart Stock Pot

Making stock is cheap and easy—if you have a stock pot. Cookin’ up a mess of greens or boiling water for pasta also requires a large vessel. You can spend a mess of green on a clad stock pot, but such models are prohibitively expensive and more than a little heavy. My favorite is stainless steel with a thick pad of metal welded onto the bottom.

One More Pan

Even if you’re positively certain that you haven’t a single pot or pan to your name, as long as you have an oven you probably do: just about every oven constructed in the free world comes with its own broiling pan. That’s right, that funny-looking enamel-coated thing with the funny little grate. Never used it? You should. It’s the perfect device for broiling. Not only does it keep food up and out of whatever juices might hinder the browning process (and broiling is about nothing if not browning) it allows said juices, including flammable fats, to gather in the pan below, where they can be rescued and put to good use. I wouldn’t say that it’s the most-used pan in my kitchen, but it is the most-oft-used pan that didn’t cost me a thin dime.

A Few Words on Lids

Heavy, well-seated, with sturdy handles. Have one for every pot or pan you own. Since not all vessels come with lids, a unilid is a great idea—and it takes up less space, too.

Stuff with Wires

Electric Skillet

An electric skillet is a must-have because of its versatility. It’s got a vast, open, non-stick plain just begging for pancakes, fried eggs, bacon, free-form crepes, pan-seared steak, and more. The thermostat keeps the oil at just the right temperature for frying, too. And best of all, even top-of-the-line models rarely cost more than thirty dollars. When shopping, look for a 12-inch model with a calibrated thermostat, sturdy design, and a tall, tight-fitting lid with an adjustable steam vent.

If I want a steak and it’s too hot in the kitchen already and I don’t have time to fire up the grill, I’ll take my electric skillet out on the screened-in porch and sear away from the comfort of my lounge chair. Not all out-of-kitchen cooking experiences have to involve a grill. I’m a big fan of electricity. Besides my electric skillet I have a nice big electric griddle, and a Crock Pot—and an electric fryer—and a toaster—and a toaster oven—and a microwave. With the exception of the microwave all the items in this list come in stove-top models. What I like about the electrical angle is control and convenience. All these devices come with thermostats, so I don’t have to fiddle too much with heat maintenance.

Tool Talk

Tongs

There’s a reason restaurant cooks call tongs their “hands.” There’s an awful lot of hot stuff in the kitchen, and there’s no better device for manipulating that stuff than spring-loaded tongs. I advocate having two pairs: a short pair for the kitchen and a long pair for the grill. Go for blunt scalloped edges, which will give you purchase without tearing; avoid those with locks, which lock up on you only when you don’t want them to. For easy storage, slip tongs inside the cardboard tube from a roll of paper towels to prevent them from opening. Tongs need not be expensive and restaurant supply stores carry them in every size imaginable.

Cooling Rack

I have a large, heavy-duty rack that fits over a large baking sheet and spans my sink. It would be hard for me to overstate my affection for this medievally simple device. Besides for cooling baked goods, I use this rack as a draining area for fried foods as well as foods I’m purging, such as eggplant or cabbage for slaw. I ovendry tomatoes on it, and on the rare occasion when I make fresh pasta I lay it on this rack to dry. When dry-aging beef in the fridge, my rack keeps it out of its own juices. When rack hunting avoid those with unidirectional wires and go with a heavy wire weave. Be sure to look for racks that have a tightly woven grid and are designed with support underneath to prevent sagging when weighted.