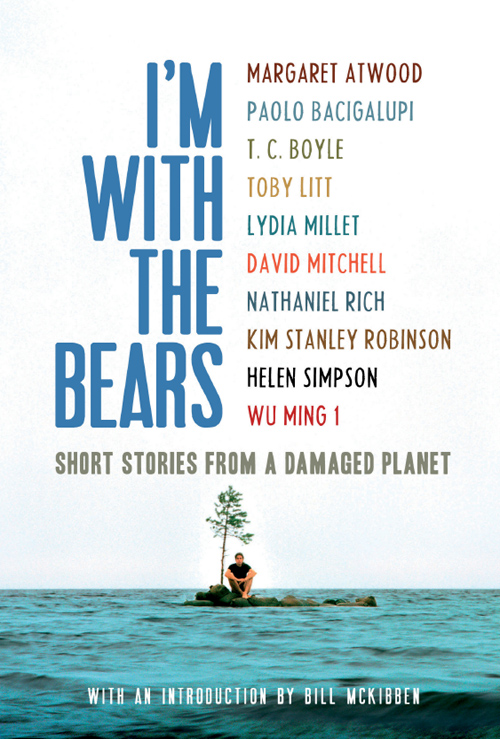

I'm With the Bears

First published by Verso 2011

The collection © Verso 2011

The contributions © The contributors 2011

“The Siskiyou, July 1989,” from

A Friend of the Earth

by T. Coraghessan Boyle

© T. Coraghessan Boyle 2000. Used by permission of Viking Penguin, a division of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Extract from

How the Dead Dream: A Novel

by Lydia Millet © Lydia Millet 2008. Used by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Extract from

Sixty Days and Counting

by Kim Stanley Robinson © Kim Stanley

Robinson 2007. Used in the US by permission of Bantam Books, a division of Random

House, Inc. Reprinted in the UK by permission of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

© Kim Stanley Robinson 2007.

“Diary of an Interesting Year” by Helen Simpson © Helen Simpson 2010.

Reprinted by permission of Rogers, Coleridge and White. Published in

In-Flight Entertainment

by Helen Simpson (Jonathan Cape 2010 [UK]; Vintage 2011 [US]).

“Time Capsule Found on the Dead Planet” reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown Group Ltd., London, on behalf of Margaret Atwood © Margaret Atwood 2009.

Translation “Arzèstula” © Romy Clark 2011

“Arzèstula” © Wu Ming 1 2009

Published by arrangement with Agenzia Letteraria Roberto Santachiara

Partial or total reproduction of this short story, in electronic form or otherwise, is consented to for non-commercial purposes, provided that the original copyright notice and this notice are included and the publisher and source are clearly acknowledged.

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

eISBN 978-1-84467-830-3

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Electra by Hewer UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in the US by Maple Vail

John Muir said that if it ever came to a war between the races, he would side with the bears. That day has arrived.

âDave Foreman,

“Strategic Monkeywrenching”

Introduction

by Bill McKibben

T. C. Boyle

Lydia Millet

Kim Stanley Robinson

Nathaniel Rich

Helen Simpson

Toby Litt

David Mitchell

Wu Ming1

Paolo Bacigalupi

Time Capsule Found on the Dead Planet

Margaret Atwood

by Bill McKibben

The problem with writing about global warming may be that the truth is larger than usually makes for good fiction. It's pure pulp. Consider the recent pastâconsider a single year, 2010. It's the warmest year on record (though not, of course, for long). Nineteen nations set new all-time temperature recordsâin Pakistan, in June, the all-time mark for the entire continent of Asia fell, when the mercury hit 128 degrees.

And heat like that has Technicolor effects. In the Arctic, ice melt galloped alongâboth the northwest and northeast passages were open for the first time in history, and there was an impromptu yacht race through terrain where even a decade before no one had ever imagined humans being able to travel. In Russia, the heat rose like some inverse of Dr. Zhivago; instead of the Ice Palace, huge walls of flame as the peat bogs around Moscow burned without cease. The temperature had never hit a hundred degrees in the capital but it topped that mark eight times in August; the drought was so deep that the Kremlin stopped all grain exports to the rest of the world, pushing the price of wheat through the roof (and contributing at least a portion to the unrest that gripped countries like Tunisia and Egypt).

And in Pakistan? Oh good God. Here's how it works: warm air holds more water vapor than cold, so the atmosphere is about four percent moister than it was forty years ago. This loads the dice for deluge and downpour, and in late July of 2010 Pakistan threw snake eyes: in the mountains, which in a normal year average three feet of rain, twelve feet fell

in a week

. The Indus swelled till it covered a quarter of the nation, an area the size of Britain. It was the first of at least six mega-floods that stretched into the early months of 2011, and some were even more dramaticâin Queensland, Australia a landscape larger than France and Germany was inundated. But Pakistanâoh good God. Six months later four million people were still homeless. And of course they were people who had done literally nothing to cause this cataclysmâthey hadn't been pouring carbon into the atmosphere.

That's our jobâthat's what we do in the West. And it's why a book like this is of such potential importance. Somehow we have to summon up the courage to act. Because here's the math: everything that I described above, all the carnage of 2010, comes with one degree of global warming. It's a taste of the early stages of global warmingâbut only the early stages. Scientists tell us with robust consensus that unless we act very soon (much sooner than is economically or politically convenient) that one degree will be four or five degrees before the century is out. If one degree melts the Arctic, put your poetic license to work. Your imagination is the limit; as one NASA research team put it in 2008, unless we reduce the amount of carbon in the atmosphere quickly, we can't have a planet “compatible with the one on which civilization developed and to which life on earth is adapted.”

So far our efforts to do anything substantial about that truth have been thwarted, completely. The fossil fuel industry has won every single battle, usually with some version of this argument: doing anything about climate change will cause short-term economic pain. And since we can understand and imagine the anguish of short-term economic pain (think of the ink spilled, and with good reason, over the recession of the last few years) we make it a priority. Since global warming seems, almost by definition, hard to imagine (after all, it's never happened before) it gets short shrift. Until that changes, we'll take none of the actions that might ameliorate our plight.

And here science can take us only so far. The scientists have done their jobâthey've issued every possible warning, flashed every red light. Now it's time for the rest of usâfor the economists, the psychologists, the theologians. And the artists, whose role is to help us understand what things

feel

like. These stories are an impressive start in that direction, and one shouldn't forget for a moment that they represent a real departure from most literary work. Instead of being consumed with the relationships between people, they increasingly take on the relationship between people and everything else. On a stable planet, nature provided a background against which the human drama took place; on the unstable planet we're creating,

the background becomes the highest drama.

So many of these pieces conjure up that world, and a tough world it is, not the familiar one we've loved without even thinking of it. Those are jolts we dearly need; this is serious business we're involved in.

But to shift, of course, the human heart requires not just fear but hope. And so one task, perhaps, of our letters in this emergency is to help provide that sense of what life might be like in the world past fossil fuel. Not just a bleak sense, but a bright one; a glimpse of what a future might look like where community begins to replace consumption. It's not impossibly farfetchedâeven in the desperate last decade, the number of farms in the U.S. rose for the first time in a century and a half, as people discovered the farmer's market, and as a new generation started to learn the particular pleasures and responsibilities that most of mankind once knew on a daily basis; in that sense, we've had writers like Wendell Berry who have been working this ground for a long time.

Of course, in the end, the job of writers is not to push us in some particular direction; it's to illuminate. To bear witness. With climate change we face the biggest single thing human beings have ever done, so big as to be almost invisible. By pointing it out, the world's writers help pose the question for the final exam humanity now faces: was the big brain adaptive, or not? Clearly it can get us into considerable hot water. In the next few years we'll find out whether that big brain, hopefully attached to a big heart, can get us out.

2011

by T. C. Boyle

This is the way it begins, on a summer night so crammed with stars the Milky Way looks like a white plastic sack strung out across the roof of the sky. No moon, thoughâthat wouldn't do at all. And no sound, but for the discontinuous trickle of water, the muted patter of cheap tennis sneakers on the ghostly surface of the road and the sustained applause of the crickets. It's a dirt road, a logging road, in fact, but Tyrone Tierwater wouldn't want to call it a road. He'd call it a scar, a gash, an open wound in the body corporal of the forest. But for the sake of convenience, let's identify it as a road. In daylight, trucks pound over it, big D7 Cats, loaders, wood-chippers. It's a road. And he's on it.

He's moving along purposively, all but invisible in the abyss of shadow beneath the big Douglas firs. If your eyes were adjusted to the dark and you looked closely enough, you might detect his three companions, the night disarranging itself ever so casually as they pass: now you see them, now you don't. All four are dressed identically, in cheap tennis sneakers blackened with shoe polish, two pairs of socks, black tees and sweatshirts, and, of course, the black watchcaps. Where would they be without them?

Tierwater had wanted to go further, the whole nine yards, stripes of greasepaint down the bridge of the nose, slick rays of it fanning out across their cheekbonesâor better yet, blackfaceâbut Andrea talked him out of it. She can talk him out of anything, because she's more rational than he, more aggressive, because she has a better command of the language and eyes that bark after weakness like houndsâbut then she doesn't have half his capacity for paranoia, neurotic display, pessimism or despair. Things can go wrong. They do. They will. He tried to tell her that, but she wouldn't listen.