Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy (21 page)

Read Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy Online

Authors: David O. Stewart

Tags: #Government, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Executive Branch, #General, #United States, #Political Science, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

MARCH 1868

I told him, I thought if he had the nerve we could make $25,000, or $50,000 out of these fellows…. I had become satisfied there was a good deal of money floating around or being gathered up…. I concluded I would see if I could not get hold of some money.

P

OSTAL

A

GENT

J

AMES

L

EGATE

, M

AY

22, 1868

F

ROM THE FIRST,

a favorite pastime of the impeachment season was “counting to seven.” With nine Democrats and three Johnson Republicans bound to vote for the president, which seven Republican senators might save Johnson from conviction by a two-thirds majority? While the lawyers planned to sway the senators with persuasive presentations, practical men focused on other means of influence. All of the political arts—from appeals to party solidarity to threats of retribution, from pledges of patronage jobs to negotiations over cash bribes—would be on display from March to the end of May.

Potential Republican defectors were identified early and the list was refined daily. Even before the House adopted impeachment articles, one Radical newspaper counted six Republican senators who might support the president. A week later, the same newspaper predicted that Kansas Senator Edmund Ross was lost, along with Fessenden of Maine and Sprague of Rhode Island. The mistrust of Sprague arose largely because Chief Justice Chase was his father-in-law. Many doubted Fessenden because he so disliked Ben Wade. A Baltimore paper reported that six Republicans would vote to acquit, while eight more were on the fence. Newspapers across the country repeated the report.

Attention focused early on Republican Senator Joseph Fowler of Tennessee, who had stood with Johnson during the secession crisis of 1860 and throughout the war. By January 1868, having soured on Johnson’s Reconstruction policies, Fowler called for Johnson’s impeachment. Once impeachment proceedings began in the Senate, though, he began to sit with the Democrats, winning a place on the list of the “doubtful.”

Both sides used every political tool at hand. The impeachers, who needed only to maintain party discipline in order to convict the president, combined demands for party loyalty with warnings of dire consequences for those who strayed from the Republican fold. Promises of positions in a Ben Wade Administration filled the air. Ben Butler developed a network of agents and spies to keep track of the doubtfuls. Butler wanted to know who those senators spent time with and what they were saying.

The president’s friends—both in and out of office—organized themselves to support his cause with patronage jobs and even bribes. These tools were familiar to experienced traffickers in influence like New York Collector Henry Smythe, Indian trader Perry Fuller of Kansas, and Sam Ward, King of the Lobby. But someone had to coordinate those efforts, to make sure that the correct inducements were offered to the correct senators, and also that they were offered only once to each. No reason to pay twice. The president’s team marshaled at least three separate efforts to offer cash to senators in return for votes for acquittal. All three ran through the hands of Edmund Cooper of Tennessee.

Cooper was the type of upper-class Southerner that Andrew Johnson often resented. Born into a wealthy cotton-trading family in middle Tennessee, Cooper attended Harvard Law School. Family connections (the Coopers were close to President James Polk) smoothed Edmund’s way. Contemporaries celebrated Cooper’s polish. One gushed over his “good breeding, gentlemanly instincts, and sense of honor,” calling him a “talented, artful man.” Andrew Johnson enjoyed none of these advantages. He came from a very different Tennessee.

Yet Cooper stuck by the Union in 1861 when two of his brothers joined the Confederates. Despite a period of detention by Southern forces, Cooper became private secretary and “confidential agent” for the military governor of Tennessee, Andrew Johnson, who was thirteen years his senior. Through their shared experience of danger and public service in wartime, the two men formed a strong bond.

After the war, Cooper served as one of Johnson’s personal secretaries in the White House before being sworn in as a congressman from Tennessee. Cooper’s fierce dedication to Johnson surfaced on the House floor when a Pennsylvania Radical referred to the president as a “usurper.” Cooper artfully called his colleague a liar, which prompted the accusation that Cooper had assisted Johnson as “the paid confidential agent of the usurper, and knew all the secrets of the usurpation.”

Cooper sought the president’s advice on political matters: whether he should run for governor of Tennessee, and how he possibly could win reelection to Congress after 5,000 blacks registered to vote in his district. After imploring Johnson to appoint him to a position that would take him out of Tennessee politics, Cooper pleaded, “Write to me! Tell me what to do!”

When Cooper lost his reelection bid, he signed on again to be Johnson’s aide, arriving in Washington City in the early autumn of 1867, as the battle over Reconstruction raged. Cooper shared the president’s combative instincts. “The more boldly you fight it out,” he advised Johnson, “the better for the country.” The president’s opponents, he warned, “intend to destroy you, if they can. They will hesitate at nothing.” Cooper pledged himself to the president’s service:

I would forego all personal and private considerations if in your estimation I can be of any service in aiding you in the great struggle for the preservation of the Government.

Back in Washington City, Cooper told Navy Secretary Welles that he would serve “as a companion and friend to the president.” Welles applauded the development. “The President needs such a friend,” he wrote in his diary, “and it is to be regretted, if Cooper is such, that he was not invited earlier.” Johnson welcomed this familiar partisan during his time of many troubles. Cooper bubbled excitedly about the experience in a letter to his father, citing the “universal approval given of my course since I have been in close proximity with the President” and the “good effect” he was having. Cooper lauded the “quiet and self-reliant courage with which the President now meets all threats or charges,” concluding, “It is a good thing that I am with him.”

The president soon determined that the loyal Cooper could be even more useful at the Treasury Department. Johnson never quite trusted his treasury secretary, Hugh McCulloch, a holdover from Lincoln’s time. Periodically questioning McCulloch’s loyalty, he considered replacing the Indiana banker but never did. Instead, he decided to appoint Cooper, his home-state acolyte, to the second position in the department. When the Senate refused to confirm Cooper for the job, Johnson left him there on an “interim” basis. Cooper’s “interim” posting would endure until the last day Johnson was in office.

From his perch at Treasury, Johnson’s “companion and friend” became the hub for schemes to influence Republican senators to vote for acquittal. The polished Southern gentleman engaged in hard-nosed bargaining with rascals and senators (groups that could overlap), acting as an unsung coordinator of the president’s most practical defense measures.

Cooper’s first opportunity to play this role came from Kansas and its rugged political culture.

Shortly after the House sent its impeachment articles to the Senate, several Kansans began to explore the crudest methods of influencing senators’ votes. The outlines of the scheme are unmistakable, though accounts of it include a forest of half-truths and undisclosed facts.

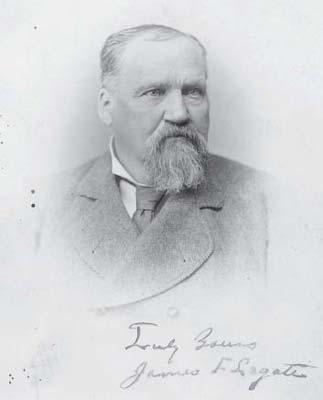

As a special agent for the Post Office Department, James Legate had a large geographic responsibility—Kansas and the New Mexico Territory. Despite those official duties, the Kansan was ordered to Washington City by the commissioner of Indian affairs, Nathaniel Taylor, a powerful patronage appointee. Taylor, formerly a congressman from President Johnson’s home region of East Tennessee, was close to the president. While in Washington, Legate performed no duties for the Post Office. Instead, he spent his time negotiating over bribes for the impeachment vote. When his leave was about to expire, it was extended upon the request of Thomas Ewing, Jr., an influential lawyer, and Senator Edmund Ross of Kansas. These powerful men took a surprising interest in a mere postal agent from Kansas. Did Taylor arrange Legate’s official leave—and did Senator Ross arrange its extension—for the sole purpose of working out bribes for impeachment votes? The available records are silent on this point.

Postal agent, and bribery conspirator, James Legate of Kansas. (The Kansas State Historical Society)

Shortly after Legate arrived in Washington City, Commissioner Taylor summoned him to discuss the case before the Senate. Impeachment, the commissioner explained, “was rather a question of brute force than otherwise; [and] if the President had brute force, enough to overcome the power against him, he would be acquitted.” A day later, the commissioner told Legate he “might make some money” from the impeachment, then turned the conversation to the Kansas senators, Ross and Samuel Pomeroy, both Republicans. The superintendent wanted to know, Legate testified later, “if there might not be some way invented by which through me [Legate], they [Ross and Pomeroy] might be induced to vote against impeachment.”

Recognizing an opportunity, Legate sought guidance from Thomas Ewing, Jr., a former Kansas Supreme Court justice who also was brother-in-law to General Sherman and the son of the pending appointee as secretary of war. Both Ewing and his father served as informal advisers to President Johnson. Ewing sent Legate to Indian trader Perry Fuller. After all, Fuller had bribed Kansas state legislators to secure Senate seats for both Pomeroy and Ross. Who would know better how to influence those two senators? Fuller also had a personal connection with Senator Ross. While in Washington City, Ross lived at the home of Robert Ream, who was Fuller’s father-in-law.

The crafty Fuller made a proposal to the postal agent that was roundabout, almost subtle. Legate, Fuller said, should organize a movement to support Chief Justice Chase’s presidential longings. This “Chase movement” could receive funds that then would be diverted to pay senators for their votes to acquit the president. Legate replied that in return “for $50,000, $25,000 down and $25,000 after acquittal,” Pomeroy could direct four Republican votes for acquittal. Legate urged that the funds be paid to a reliable third party who would hold them for the “Chase movement.” After the senators voted to acquit the president, the third party could deliver the funds to the senators’ agents.

Under this scheme, Legate and Fuller intended not only to bribe senators, but also that the middlemen (them) would help themselves to some of the “Chase movement” funds. To this end, Legate joined up with another opportunist who dwelt in the shadows of government. Willis Gaylord, a New Yorker who was Senator Pomeroy’s brother-in-law, had acted for Pomeroy in earlier payoff schemes involving land grants to Kansas railroads and treaties to acquire Indian lands. Gaylord, again acting for Senator Pomeroy, angled to be the stakeholder of the $50,000 in bribe money.

Perry Fuller took Legate to see Edmund Cooper, the president’s man at the Treasury. Jointly, Cooper and Fuller instructed Legate on a key political consideration. The president, they boasted, could call on the vote of Kansas Senator Ross if needed, but that could be controversial for Ross in Republican Kansas. To limit Ross’s political risk, they wanted the other Kansas Republican (Pomeroy) also to vote for acquittal. They were willing to pay for Pomeroy’s vote.

The courtly Cooper instructed Legate on how the bribe money could be raised. Tax collectors in New York and New Jersey had seized large amounts of whiskey on which federal tax had not been paid. Cooper, showing Legate a list of the seizures, said that Legate could earn commissions by helping to settle those cases. Those commissions could pay for bribes to senators, with some money left over for themselves. Two days later, Legate took the train to New York to complete this mission. Lists of whiskey seizures in the New York area were prepared. Within a few days, however, Treasury officials cooled on the project. Legate returned to Washington City empty-handed, resolved to renew his scheming with Gaylord and Cooper. He became a regular visitor to Cooper’s room in the Metropolitan Hotel as he pressed the Treasury official to find another way to conclude a bribery deal.

The resumed negotiations advanced to the point of concrete proposals about specific sums. Gaylord promised that $40,000 would ensure the pro-Johnson votes of Pomeroy and four other Republican senators. Cooper authorized Perry Fuller to offer $40,000 for the “Chase movement,” with the money to be paid if the Senate acquitted Johnson. In one version, Cooper met with Gaylord and counted out most of the money in cash, then added a check drawn on a Washington bank. Gaylord declined the payment, in this account, because he would not accept the check.

Though the schemers admitted engaging in extensive bribery foreplay, they tended to deny that there was any consummation. Cooper claimed that during negotiations over the payment to Gaylord, he began to suspect that the New Yorker’s overture might be a trap, that Cooper’s efforts to purchase senators’ votes could be revealed publicly to embarrass Johnson.

THE KANSAS CABAL