Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy (22 page)

Read Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy Online

Authors: David O. Stewart

Tags: #Government, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Executive Branch, #General, #United States, #Political Science, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

Senator Samuel Pomeroy | Radical Republican who proposed Cabinet changes to President Johnson to defeat impeachment, and whose agents negotiated for bribes for several Republican senators. |

Senator Edmund Ross | Radical Republican who (like Pomeroy) owed his Senate seat to bribes paid to Kansas state legislators. |

Perry Fuller | Indian trader who bribed Kansas legislators to win seats for Pomeroy and Ross, and sought to head the federal tax agency. Assisted Legate in a proposal to bribe senators to vote to acquit. |

James Legate | Postal agent detailed to Washington; negotiated with Treasury official Edmund Cooper for bribes to Republican senators. |

Willis Gaylord | New Yorker and brother-in-law of Pomeroy; negotiated with Cooper on behalf of Pomeroy and others for bribes. |

Robert Ream | Landlord of Senator Ross; father-in-law of Perry Fuller. |

Thomas Ewing, Jr. | Adviser to President Johnson and Senator Ross, former Kansas Supreme Court Justice, and brother-in-law of Gen. Sherman; helped Legate advance a scheme for bribing senators. |

Perhaps the most remarkable part of the Kansans’ saga is that their scheming reached into the White House, into Andrew Johnson’s office. In late March, postal agent Legate persuaded a representative (probably Fuller or the younger Ewing) to deliver a message to a Johnson aide: If the aide would ask Senator Pomeroy for his opinion of Legate, the ensuing conversation “would open up the way of securing half a dozen radical votes for the President.” When the aide described Legate’s message to the president, Johnson understood its significance immediately. He replied that he preferred conviction with a clean conscience to acquittal by nefarious means.

That was what the president said. But Senator Pomeroy made a similar overture to the White House and met a different reception. Pomeroy sent a message to Johnson: If the president would change his Cabinet, impeachment would halt. “Impeachment,” Pomeroy’s message insisted, should be viewed “as a

political

, not a

legal

question.” Johnson again reacted indignantly, announcing to his staff, “I will have to insult some of these men yet.” The president’s huffy response may have been due to the source of the proposal. Pomeroy, a Radical and hardly a Johnson ally, had a noisome reputation for mixing corruption with sanctimonious Christian piety. The Kansan’s hypocrisy was so notorious that he served as the model for Mark Twain’s avatar of venality, Senator Dilworthy, in his novel

The Gilded Age

.

Despite his pious protestations, the president met with Pomeroy early the next morning. He did not use the occasion to insult the senator. Afterward, Johnson related an innocuous version of this meeting. According to the president, the Kansas senator said nothing of changing the Cabinet, but offered a few tepid comments about current Cabinet officers. After a “very friendly” talk, Pomeroy supposedly departed with the wish that Johnson give him “suggestions that might tend toward producing a good effect in the present condition of affairs.”

Johnson’s bland account of his conversation with Pomeroy concealed far more than it revealed. In the midst of the impeachment crisis, two such veteran politicians were not likely to pass the time exchanging vague niceties about Cabinet officers. Certainly not when, as Johnson admitted, “several persons” had urged him to talk to Pomeroy. (Was Cooper one of those urging him?) The Kansas senator had a definite agenda for the meeting, and no doubt pursued it. Perhaps he pressed for changes in the Cabinet. Perhaps the proposal for a Cabinet shakeup morphed into a bold demand for control of federal patronage jobs in Kansas, or an even bolder demand for a bribe. Though the president had protested that he would not bargain for votes, for the next two months Senators Ross and Pomeroy would figure in many discussions of what type of bargain might bring them to vote for acquittal.

The Kansans were the first, but they were not the only ones thinking about how to use money to influence the Senate’s verdict. A second plan came from more august sources. Three of Johnson’s Cabinet members established a war chest for bribing Republican senators. Once more, the scheme ran through the hands of Edmund Cooper at Treasury, Johnson’s trusted supporter.

This plan originated with Secretary of State Seward, Treasury Secretary McCulloch, and Postmaster General Alexander Randall. The three high officials fretted that the president might well be convicted and removed from office. They convened a conference with an expert on corruption, printing executive Cornelius Wendell. A Democrat who performed all federal printing contracts in the 1850s, Wendell was a notorious figure in Washington City. He operated a political slush fund in the years before the Civil War, using excess payments from his government contracts to support Democratic newspapers and make contributions to Democrats around the nation. In a six-year period, Wendell received $3.8 million for public printing (at least $50 million in current dollars), more than half of which was pure boodle. That arrangement, directed by President Buchanan himself, led another Democrat to call Wendell “that most corrupt of all men.” In but one example, in 1858 Wendell spent $40,000 (at least $560,000 in current dollars) to push legislation through Congress.

Although Wendell’s graft and bribery were exposed in congressional hearings in 1860, President Johnson made him Superintendent of Public Printing. One Wendell sponsor said he had recommended the scoundrel to Johnson “as Gen. [Andrew] Jackson employed Lafitte the pirate. He knew the intricacies of the mouth of the Mississippi and would be able to detect the approaches of the enemy.” That sponsor later recanted his recommendation, admitting, “Wendell has joined the knaves whom he supplanted.”

The three Cabinet officers had a pressing question for this infamous character: how much would it cost to assure the president’s acquittal? After some hedging, Wendell estimated that $150,000 (over $2 million in today’s money) should do the job, though he refused to handle the funds himself. After the impeachment trial ended, Wendell recalled that the entire amount was raised and placed in an acquittal fund. Some came from Postmaster General Randall, some from Treasury Secretary McCulloch. Much was raised by “outsiders.”

Contributors to the acquittal fund doubtless included the many government contractors and patronage employees whose livelihoods depended on the continuation of the Johnson Administration. Some came from employees of the custom houses in Baltimore and Philadelphia. More came from whiskey distillers who evaded taxes by bribing Johnson’s tax men. Collector Henry Smythe, who presided over the golden river of revenue at the New York Custom House, was eager to help. He sent a deputy to the White House to inquire about the best way to pay the president’s defense costs. After all, three months earlier Smythe had collected funds from every employee in his domain for the stated purpose of helping the president with impeachment. Moreover, Smythe was now after a foreign posting, the plum position of minister to Great Britain. A man seeking high appointment will want to be useful. Colonel Moore, Johnson’s aide, referred Smythe’s man to William Evarts, the president’s lawyer from New York, so they could arrange money matters “in a quiet way.” Moore warned that “extreme caution was necessary.”

The acquittal fund was assigned to the care of Cooper and Postmaster General Randall, who jointly controlled it. The inconspicuous Cooper thus coordinated a second major scheme for buying impeachment votes. Before the trial ended, at least one more corrupt intrigue would land on his desk.

While the fixers plotted, the trial loomed as a momentous event in the nation’s life, nowhere more so than in the South. Southern Unionists and freedmen, outnumbered and beleaguered, held their breath. “The impeachment of the President,” wrote an Alabama Republican, “will be a death blow to the rebellion, still strong with life.” An army commander in Kentucky reported that the “rebels” were alarmed by the impeachment. “Here in the South,” he added, “we cannot calmly think of the failure of impeachment and the long train of evils that would follow in its wake.”

As each day passed, every participant in the trial could feel the lens of history beginning to focus. The House managers went to Mathew Brady’s gallery to sit for a group photograph, a grim affair in which some resemble avenging angels, others seem befuddled to be there at all, and only James Wilson looks like a potentially pleasant dinner companion. Stevens learned that teenage sculptor Vinnie Ream had completed a statuette of him. Ms. Ream, the precociously talented daughter of Senator Ross’s landlord, Robert Ream (and thus sister-in-law to Indian trader Perry Fuller), was eager to show the work to Stevens, who doted on her. Ben Butler worked feverishly on his opening speech in the Senate, his opportunity to frame the constitutional contest. Through three days of preparation, he slept only nine hours, refusing to meet his many callers, aided by a team of stenographers and an Ohio congressman. No other manager lent a hand.

The troubled president sought solace in history and in familiar things. He read and reread Addison’s

Cato

, committing parts to memory and comparing present-day senators to those portrayed in the play. He reflected at length on a sermon he heard at St. Patrick’s Church, observing that there was nothing more depressing than “to labor for the people and not be understood. It is enough to sour [a man’s] very soul.” Then he was back to ancient Rome, comparing his situation to that of the Gracchi brothers, tribunes of the people who were murdered at the instigation of the Roman Senate. “This American Senate,” he insisted, “is as corrupt as was the Roman Senate.” Johnson dug out a weathered collection of political speeches, the first book he ever owned, given to him before he learned how to spell. He turned to the speeches of Lord Chatham (William Pitt the Elder), denouncing British policy toward the American colonies. Johnson lingered over Chatham’s statement that “no tyranny is so formi[d]able as that assumed and exercised by a number of tyrants.” For Johnson, the parallel to Thad Stevens’s Congress was unmistakable.

Johnson’s closest adherents expected the worst. Navy Secretary Welles judged that every member of the Cabinet thought the president would be convicted.

But the unexpected can happen in a trial, and in politics. Everyone was nervous. Everyone was excited. The battle was about to be joined.

MARCH 30–APRIL 8, 1868

[The impeachment committee] put in the forefront of its battle a lawyer whose opinion on high moral questions…nobody heeds…and whose want…of decency, throughout the case gave the President a constant advantage.

T

HE

N

ATION

, M

AY

21, 1868

E

VEN BRASH BEN

Butler felt intimidated. Waiting to give the opening statement on the first full day of trial, Monday, March 30, “I came as near running away then as ever I did on any occasion in my life.”

Rising to address the Senate, Butler was not a commanding figure. One observer described him as “short, broad-shouldered, short-legged, fat, without much neck, but with a good many flaps around the throat, standing as if a trifle bow-legged…[with] a great cranium of a shining pink color.” Another complained of his raspy voice, like a cross-cut saw. A third deprecated his enunciation as “neither silvery nor distinct.” On this day, Butler lost his usual swagger. Cowed by the significance of the moment, he clutched his papers close to his face while nervously reading a three-hour speech.

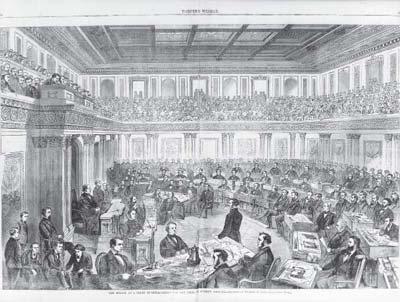

Crowded to suffocation, the Senate galleries bloomed with bright feminine costumes. Many remarked on Butler’s daughter Blanche, her youthful beauty contrasting with her father’s singular appearance. Equally lovely were Chief Justice Chase’s daughter Kate, whose husband Sprague was at his desk on the Senate floor, and the notorious former Confederate spy, Belle Boyd, with “very black eyes and a very blue veil.” Only two “Africans” were there, as was British Ambassador Edward Thornton.

Ben Butler delivers the opening statement for the prosecution, March 30.

The managers sat at the table to the left of the chief justice, facing him. The table for the defense team was to the right. Butler regretted that the prosecution was “too weak in the knees” to demand that Johnson attend the trial. The Massachusetts Radical had argued for compelling his appearance, forcing him “to stand until the Senate offered him a chair.” In truth, Johnson ached to gratify Butler’s wish. That morning, he felt again “strongly impelled” to attend the trial. His lawyers once more dissuaded him from being Exhibit A in a spectacle managed by Ben Butler and Thad Stevens. Allowing himself to be dragged into the Senate would diminish the presidency, they argued. Johnson should remain above the battle.

Though many listeners were disappointed by Butler’s restrained presentation that day, the speech was as solid as the ill-constructed prosecution permitted. Eight impeachment articles focused on the confrontation between Stanton and Thomas, and the Tenure of Office Act. Butler emphasized those articles, charging that the president claimed a “most stupendous and unlimited prerogative” to ignore the statute when he replaced his war secretary. The manager admitted that the last three articles—the General Emory charge, Butler’s own stump-speech article, and Stevens’s catchall Article XI—were diminished by the “grandeur” of the first eight. Butler thus created a logical inversion, calling the eight narrow articles (thought “trifling” by Stevens) truly grand, and disparaging the three broad ones as slight. To justify all eleven articles, the manager had to define an impeachable offense expansively; it was, he said, any act that subverted a “fundamental or essential principle of government or [was] highly prejudicial to the public interest.” The question before the Senate, he contended, was whether Johnson, “because of malversation in office, is no longer fit.”

In a passage that drew much criticism, Butler told the Senate that it was “bound by no law, either statute or common.” The senators, he continued, were “a law unto yourselves, bound only by natural principles of equity and justice.”

Without an explicit constitutional provision granting or denying Congress the power to adopt the Tenure of Office Act, Butler marshaled the historical precedents that supported the statute. In

The Federalist

, Alexander Hamilton had insisted that the Senate’s consent would be necessary under the Constitution “to displace as well as to appoint.” Not only had Congress in the 1790s defined the president’s power to remove high officials, but it again asserted its power over the question in 1863 when it set a term for the comptroller of the currency, and in 1866 when it directed that military officers could be removed only by impeachment. Johnson himself signed the 1866 statute. Johnson followed the procedures of the Tenure of Office Act when he suspended Stanton the prior August. The House manager agreed that Johnson could challenge the constitutionality of a law by violating it, but only at his peril. “[T]hat peril,” Butler continued, “is to be impeached for violating his oath of office.” Butler botched his discussion of Article XI, stating incorrectly that acquittal on the other charges would require acquittal on the catchall article.

Butler offered the customary comparisons between the president and despots of yore (Caesar and Napoléon). He described Johnson as “thrown to the surface by the whirlpool of civil war,” and acceding to the presidency as “the elect of the assassin,…and not of the people.” Butler blamed Johnson for Southern murders of freedmen and white Unionists, “encouraged by his refusal to consent that a single murderer be punished, though thousands of good men have been slain.” On the Senate’s verdict, he warned, the welfare and liberties of Americans “hang trembling.”

Managers Wilson and Bingham then read into the record the prosecution’s first evidence, the presidential oath of office and the president’s December letter justifying his removal of Stanton under the Tenure

of Office Act. Having sat from 12:30 until 5

P.M.

, the Senate called it a day.

The prosecution’s case took five days to present, with the Senate sitting as a court from noon to five, through Saturday. In the unseasonably warm weather, it seemed longer. Throughout the week, attendance declined in the galleries and among the congressmen. Ladies brought knitting and novels to their seats. Senators wrote letters at their desks. The fourth day was the nadir, according to one newspaper, “intensely dull, stupid, and uninteresting.” By Saturday, April 4, senators had to be herded back into the chamber after a recess, and the galleries were half-empty. Fewer than fifty House Republicans showed up for the hearings on Friday and Saturday, some playing hooky to catch the afternoon show of Dan Rice’s traveling circus. (The circus included a political element befitting the season; the animal acts were interspersed with pro-Johnson monologues by Mr. Rice.) When Butler announced the end of the prosecution case, impeachment supporters were deflated.

Some sense of anticlimax was unavoidable. No one could sustain the fevered emotions of the early impeachment days. Moreover, the taking of factual evidence is mostly a businesslike affair. Even in the Senate Chamber, the rhythmic catechism of question and answer offers few opportunities to cry out for justice or to compare adversaries to legendary tyrants.

Also, everyone already knew the interesting facts. Newspapers had printed complete accounts of the confrontation at the war office, plus summaries of the testimony taken by the House managers in their preparations. President Johnson’s unfortunate addresses in 1866—the basis for the stump-speech article—had circulated around the nation. Compelling testimony might have come from Edwin Stanton, but the managers had good reasons not to present him. If Stanton left his office for an afternoon, Lorenzo Thomas could slip in and change the locks, undermining the case. Also, Stanton could be a disaster as a witness. He would have to explain why he should remain in office against the wishes of the president he had assiduously disserved. A skilled cross-examiner might goad Stanton into revealing his native arrogance, an unattractive quality in a witness. Butler likely was content to leave the war secretary undisturbed at his bivouac.

Left with mostly dull testimony, Butler did the best he could. The first meaty witness was the fourth one, a Republican congressman from Niagara County, New York. Burt Van Horn, one of the group in Stanton’s office when Thomas arrived on February 22, was the shorthand writer who jotted down on an envelope the exchange between dueling war secretaries. Another Republican congressman who was then in Stanton’s office echoed Van Horn’s testimony.

With the sixth witness, the congressional delegate from the Dakota Territory, Butler began to take the wheels off his own case. Walter Burleigh was a friend of Adjutant General Thomas. Butler wanted Burleigh to relate Thomas’s statements on the evening of February 21, before the adjutant general attended the masquerade ball at Marini’s Hall. Stanberry objected that the testimony was irrelevant. When a senator requested that the objection be submitted to the Senate for decision, the chief justice demurred. Referring to himself in the third person, Chase announced that “the Chief Justice is of opinion that it is his duty to decide preliminarily upon objections to evidence.” If a senator disagreed with the chief justice’s ruling, he could ask the Senate to overrule it.

On every possible ground, Butler objected. Chase’s procedure would bias evidentiary rulings during the trial, he argued, since the Senate would defer to the chief justice’s initial decision on an issue. Worse, the House managers could not themselves appeal for a Senate vote, but would have to rely on some friendly senator to do so. Reciting seventeenth-century English precedents, Butler expressed concern that Chase’s procedure could be abused by a future chief justice who would not be as admirable a jurist as Chase: “We have had a Johnson in the presidential chair,” he warned, “and we cannot tell who may get into the chair of the Chief Justice.” Having sat quietly for almost two days, Managers Bingham and Boutwell chimed in. Then Butler popped up with a few more choice remarks.

The Senate’s response was utter confusion. After wrangling through five inconclusive roll-call votes on procedural motions, the senators retired for an executive session on the subject. Then the Senate adopted a rule that followed Chase’s proposed procedure. Adjournment at 6:30

P.M.

was a blessing.

That evening, the defense team must have chuckled all the way back to the White House. Defense lawyers ordinarily yearn for procedural snarls and quibbles over motes—anything that will distract the court from the prosecution case. With only slight provocation from the imperious Chase, the managers and the Senate had sunk into the sort of contentious squabble that the defense craved. What a capital sight, watching the managers climb over each other in their eagerness to derail their own case with indignant speeches on a not very important dispute! After battling manfully over the Senate’s procedure for resolving evidentiary issues, what senator could even remember Burleigh’s testimony, much less that the fate of the Republic hung in the balance?

The next morning, the managers, at their regular pretrial meeting at 11

A.M.

, fumed over the Senate’s failure to adopt a rule that would bar the chief justice from casting a tie-breaking vote (as the vice president does in legislative matters). Butler proposed that the managers withdraw from the trial in protest. They should, he said, ask the House of Representatives for instruction on the question. Though supported by Stevens and Boutwell, his proposal lost 4 to 3. After the managers trooped into the chamber, Senator Charles Sumner proposed a rule to bar such a tie-breaking vote by the chief justice. The motion lost.

At this point, the advocates settled in for two more hours of debate over whether Delegate Burleigh should be allowed to relate his conversation with Lorenzo Thomas. Finally, by a margin of 39 to 11, the Senate said yes. The payoff for this stupefying exercise was Burleigh’s description of the adjutant general’s presumably inebriated pledge to take control of the War Department Office, to “meet force by force,” and to break down any doors that were barred to him. Butler had used more than four hours of the Senate’s time to secure a few minutes of mildly titillating testimony that would sway not a single vote.

The Senate Chamber during the impeachment trial.

The president’s lawyers recognized the opportunity before them. They started to use the evidentiary procedures to have some fun. William Evarts interposed frequent objections to Butler’s questions, triggering the same excruciating sequence. If Butler rephrased the question to meet the objection, Evarts raised a new one. And another. Finally, in exasperation, Butler would write out his question and hand it to the chief justice to read to the Senate. The lawyers then exchanged volleys over the virtues and vices of the written question, and a roll-call vote would decide whether the witness had to answer. If the Senate allowed Butler to press that question, Evarts protested the next one.