Importing Diversity: Inside Japan's JET Program (12 page)

Read Importing Diversity: Inside Japan's JET Program Online

Authors: David L. McConnell

While Wada and others in the high school education section were cool

to the JET proposal, in the end their superiors agreed to the new plan under which the Ministry of Education would supervise the team-teaching dimensions of the program. I asked Wada whether outside pressure was involved in this decision, and he replied:

We discussed the idea for about three months-is it good to join the

new project or is it better to stay with the old? During that time, there

was no pressure openly from any other ministries or sources of power.

But the final decision in our ministry was made by higher-ranking officials at the kyoku (division) level. I'm not sure, but I guess there was

very strong pressure on high-ranking officials of our ministry from the

prime minister or from the Ministry of Home Affairs. There were some

political and economic reasons that motivated Home Affairs. The prime

minister at that time was Mr. Nakasone, and he was very eager to show

that he took an interest in relations between Japan and foreign countries. The kyokucho (division chief) must have felt some pressure from

Nakasone's office in a very subtle way.

Whether there was direct pressure or not, Education officials clearly perceived that their choices were constrained, and they conveyed this sentiment to local educational administrators. One educational administrator in

Osaka recalled: "When the decision was made to go ahead with the JET

Program, we [English curriculum specialists at the prefectural level] were

called to Tokyo by the Ministry of Education for an urgent meeting. They

told us that the ministry had not been adequately consulted about the plan

and would never have increased the numbers of participants so rapidly. The

Ministry of Education was very upset and felt that their program had been

taken away from them (torarete shimatta)."

The ministry did set one condition for its support, however. It would go

along with the program only if it was made clear that the foreign participants served as assistants to the regular Japanese language teacher: thus

Japanese teachers would not feel that their own jobs were either legally or

symbolically threatened by the influx of native speakers. The resulting

compromise gave rise to what has become one of the most talked about and

controversial aspects of the program: team teaching. Wada explained, "I

myself thought a lot about that [the issue of Japanese teachers worrying

about losing their jobs]. I didn't want Japanese teachers of English to think

that I didn't pay attention to that aspect. The idea of team teaching has

something to do with that issue. When you look at the situation at private

schools, they don't do team teaching because the owners of private schools

don't want to spend money on both a native speaker and a Japanese teacher.

They think they don't need two teachers."24 It is worth noting that the title

initially given to the JET participants-"assistant English teachers" (AETs)

and later "assistant language teachers" (ALTs)-symbolized an important lowering of status from "English fellows," the name used throughout most

of the MEF Program.2s

It was also striking that the Ministry of Education's approval of the JET

Program did not lead to any formal resistance from the Japan Teacher's

Union, which has systematically opposed virtually every postwar initiative

offered by the ministry. Although some union members did attack the program, the overall response was quite muted. Wada clarified the apparent

contradiction: "What is very interesting is that union leaders are against

the JET Program on the surface. If they are asked whether they support

government efforts to invite JET participants, they say no ... but union

teachers like to work with ALTs. So they cannot oppose the JET Program in

the same way they oppose other policies promoted by government. Union

teachers have been pushing for communication-oriented English and for

internationalization for a long time. 1116

Thus, although the Ministry of Education finally acceded to the JET

proposal, it is fair to say that those officials who would actually have a

hands-on role were at best lukewarm to the idea. Moreover, a surprisingly

small number of people were actually involved in the decision. At no time

were discussions held with the textbook oversight committees or other

groups that shaped the larger structure of English education in Japan. Instead, the JET Program would simply be added on to existing policies, with

all the glaring contradictions that would inevitably follow.

SETTING INITIAL PROGRAM POLICY

Once a tenuous alliance between the three sponsoring ministries had been

forged, it remained for a planning committee consisting of representatives

from each to set initial program policy. What were the decisions about program structure that were explicitly debated, and how were they resolved?

What were the "nonissues"-that is, on what aspects of program policy did

broad agreement already exist?

The most immediate problem arising from the diverse sponsorship of

the new program was to articulate the "official" statement of program

goals for the press release on 8 October 1986. The intersectoral nature of

the policy meant that program goals had to be worded so as to please all

three sponsoring ministries-the diplomatic goals of Foreign Affairs, the

local development goals of Home Affairs, and the foreign language-teaching

goals of Education. Insofar as the JET Program was a response to American

pressure, the statement of purpose also had to be couched in terms that sat isfied the critique of Japan as a closed society. What emerged after much deliberation was an exceedingly broad statement designed to satisfy each of

the above constituencies:

The Japan Exchange and Teaching Program seeks to promote mutual

understanding between Japan and other countries including the U.S.,

the U.K., Australia, and N.Z. and foster international perspectives in

Japan by promoting international exchange at local levels as well as intensifying foreign language education in Japan.21

Another major decision regarding program policy was how to structure intergovernmental linkages. Who would be responsible for which aspects? I was quite surprised to find Japanese ministry officials referring to

JET as a "grassroots" exchange program, calling up images of ideas and

actions bubbling up organically from volunteer networks in local communities. It would seem to be the direct antithesis of governmentsponsored programs.

But Japanese sensibilities gave a different flavor and meaning to the

term. For the national-level bureaucrats, there was never any question that

"grassroots internationalization" needed both impetus and management

from the top. National-level ministries, in spite of being highly compartmentalized, all view the policy process similarly. Put simply, ministry officials subscribe to a theory of top-down change that sees the national government providing training of, encouragement to, guidelines for, and

subtle pressure on prefectural governments, who in turn leverage the next

level of the system; this process continues downward until satisfactory policy outcomes are achieved. The theory is that enough muscle applied at

each level will eventually bring compliance."

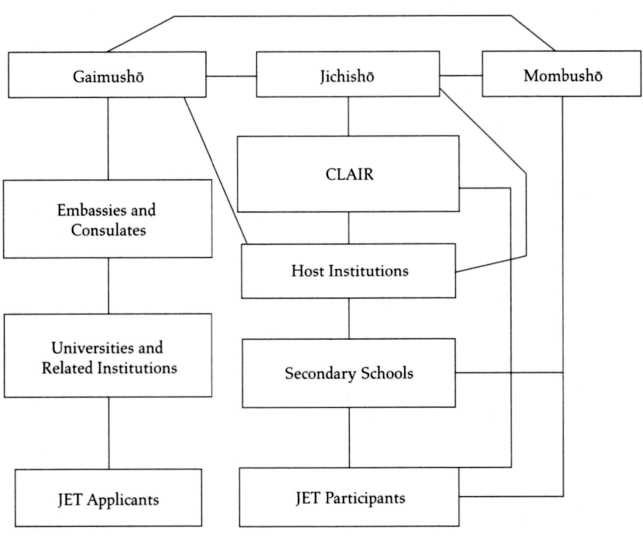

The formal administrative structure of the JET Program that resulted

from this approach is shown in figure i. Local initiative was to be encouraged, and employment contracts were to be signed with the local

host institution (prefecture or municipality), which could request the

number and kind of JET participants desired each year. That local institutions, not a national-level body, were designated as the "official employers" goes a long way toward explaining the variation in working conditions experienced by JET participants (see chapter 4). Nonetheless, local

autonomy played out within a framework set largely at the national

level. The sponsoring ministries would make key decisions about programwide policies and the annual number of participants; they would

provide the services of selection and placement in host institutions; and they would coordinate the Tokyo orientation, midyear block conferences,

and other support services.

Figure 1. Formal administrative structure of the JET Program. Source: Advertising brochure, The JET Programme, 1995-96 (Tokyo: Council of Local Authorities

for International Relations, 1995), n•p.

CLAIR: A Cultural and Structural Broker

At the center of JET Program administration stands the Council of Local

Authorities for International Relations (Jichitai Kokusaika Kyokai), more

commonly known by the acronym CLAIR. With its own staff and building, this nonprofit, quasi-governmental agency is responsible for the dayto-day management of the program at the national level.29 Like most Japanese organizations, CLAIR consists of an entirely symbolic advisory

council; it was initially chaired by Shunichi Suzuki, the former mayor of

Tokyo. Significantly, it also serves as a "retirement post" (amakudari) for

one former bureaucrat from each of the three sponsoring ministries. In

theory, these individuals are to serve as liaisons with their respective min istries, but in fact they are quite marginal to the day-to-day operations of

CLAIR.

Appointments to CLAIR are made by the Ministry of Home Affairs,

local governments, and private companies in fairly regular patterns. As one

corporate representative noted, "There was a strong feeling that the JET

Program could never be made to work solely by the power of the hard

heads of bureaucrats." There are representatives from Kintetsu Travel

Agency and Daiichi Kangyo Bank, as well as lower-level staff from selected

prefectural and municipal offices. These staff members usually serve one

year in CLAIR's Tokyo office and then a second year in one of the growing

number of overseas offices (they serve as windows on the world for the

Ministry of Home Affairs).

But in spite of the presence of these representatives, CLAIR is beyond

question an administrative arm of the Ministry of Home Affairs. The top

three CLAIR officials in terms of day-to-day decision making-the

secretary-general, the deputy secretary-general, and the General Affairs

section chief-always come from Home Affairs; and since these upperlevel staff must return to that ministry after their appointment in CLAIR,

they have little incentive to exercise independent judgment or initiative.

Other than the amakudari, the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Education

are not represented in CLAIR, and the only person with educational experience is the chief of the Counseling and Guidance Section (shidoka). The

result is a government-business alliance in which educational specialists

are marginalized.

Most intriguing is the employment in CLAIR of a handful of JET Program alumni as liaisons between the Japanese staff and the mass of JET

participants. Sometimes called "gaijin handlers" because they coordinate

large numbers of foreigners, their primary responsibility is to manage the

flow of information to and from the JET participants and to assist in those

aspects of program implementation that require the linguistic and interactional skills of a native speaker. In the same way that Japanese officials at

CLAIR act as brokers between national ministries and local host institutions, the program coordinators, by their own admission, serve as buffers.

One, rather uncharitable in his depiction of the Japanese staff, put it this

way: "There's no question we're used as buffers. All information to ALTs

goes through the program coordinators. We always have to break the bad

news because if they [the Japanese staff at CLAIR] do it, they come across

as bureaucratic sods. The less contact they have, the better." In theory, assuming good coordination within the CLAIR office, there would be no

need for the Japanese staff at CLAIR to become directly involved with JET participants, nor for the program coordinators to negotiate with local Japanese officials. But on numerous occasions (regional block meetings, crisis

intervention, etc.) both Japanese and foreign staff at CLAIR have entered

into direct negotiations with JET participants and local Japanese officials.

As an administrative office, CLAIR is in a very delicate position. It must

negotiate with a whole host of ministries and agencies at the national level,

with local governments throughout the country, and with the thousands of

JET participants themselves. Though CLAIR has little input on major policy decisions, the Japanese staff and the program coordinators have considerable power when it comes to shaping program content.

Participating Countries

Having embarked on an ambitious plan to enhance Japan's valuing of diversity, the next decision government leaders faced was selecting those

who qualified for inclusion. Four countries were invited to join the JET

Program in its inaugural year: the United States, Britain, Australia, and

New Zealand. Canada and Ireland were added in 1988, and France and Germany joined in 1989 (see chapter 3), for a total of eight countries participating in the ALT component of the program. Table 1 shows the breakdown of ALT participants by country for JET's first five years.

The already functioning MEF and BET programs made the choice of the

United States and Britain obvious. In fact, participants were given the option of renewing their contracts and staying on in Japan under the JET

Program.j0 The addition of Australia and New Zealand was engineered primarily by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Now that the English program

was loosened somewhat from the viselike grip of the Ministry of Education, diplomatic considerations could be entertained. Japanese language

study was booming in those countries, and both had been knocking on the

door for admission to the MEF and BET programs for some time. Significantly, their participation would not greatly increase the overall number of

applicants.