Importing Diversity: Inside Japan's JET Program (40 page)

Read Importing Diversity: Inside Japan's JET Program Online

Authors: David L. McConnell

In some cases, ALTs actually instituted special "international understanding classes" (kokusai rikai no jikan) apart from the regular English

curriculum; but for others, who encountered cooperative or cowed JTLs,

the regular team-taught class provided their opportunity for experimentation. One Canadian ALT in a Tottori-ken high school, for instance, did a series of global education classes designed to point out gross economic inequities around the world. They included a simulation on the cacao trade to

show how multinationals and foreign banks create poverty among smallscale farmers in Africa, as well as two classes on human rights. She explained, "I have the students fill in a questionnaire about human rights in

Japan. I point out that Japan is the only non-communist country to have ministry-authorized textbooks and I also show them my fingerprints on

my Alien Registration Card (yes, according to this card I come from outer

space ... )."" The highlight of this class occurred when, in the middle of

winter, she posted signs on the two doors of the classroom. Her door, which

was near the kerosene heater in the back of the class, said, "Whites Only:

No Japanese Allowed," while students entered through a door leading to

the colder part of the classroom. That such classes were even permitted testifies to the extraordinary degree of discretion allowed to individual teachers and schools in spite of Ministry of Education guidelines. However, I did

hear of several cases in which ALTs were told in no uncertain terms by the

principal that classes with an overt political message were inappropriate.

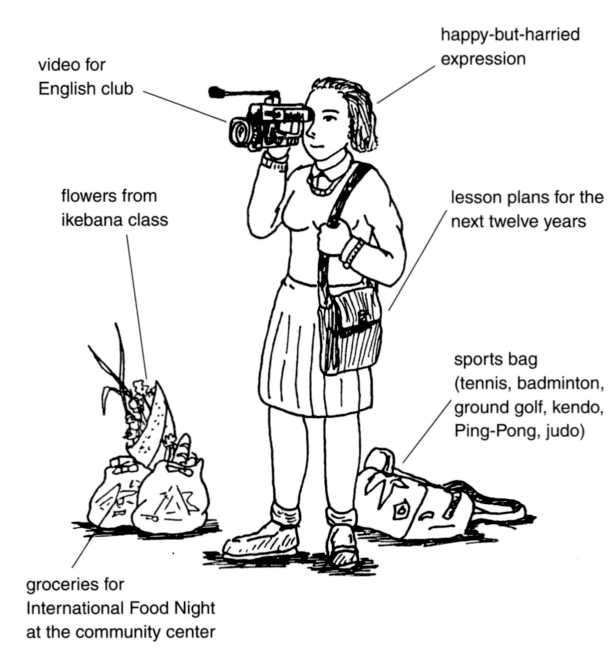

The Overachiever (Homo sapiens excessive). Distinctive call: "Culture shock?

Who has time for culture shock?"

To be sure, within this broad group ALTs displayed different levels of

cultural sensitivity. At one extreme were those who embraced reform with

a self-righteous zeal that was off-putting to all but the most radical JTLs;

at the other extreme were "sensitive change agents," who worked within

the structural limitations of their position. They were often able to find

gratification and meaning in cultivating relationships with a select group

of students and teachers, particularly those who were enthusiastic about

foreign language learning and who seemed open to learning about the

world. This latter approach was one that CLAIR and the Ministry of Education actively supported, and it is no surprise that in 1995 the winning

essay of the Third Annual JET Programme Essay Competition took up this

topic. In "More Than a Language Teacher," Jeffrey Strain found the lasting

significance of the JET Program in ALTs' interactions with students outside the language classroom. He suggested a number of possible activities:

joining after-school clubs, participating in other classes and in field excursions, creating other responsibilities at school, writing a monthly newsletter, working where students have access to one, and even wandering

around the school asking questions. "Classroom time is now only a small

fraction of the time I spend with the students, where in the past it had constituted the majority," he noted. "I currently try to spend a minimum of 5o

percent of my time at school in contact with students outside the classroom." 17

The Careerists

Among the ALTs, as among the JTLs, were some who saw the JET Program

in narrowly instrumental terms. For them, it was primarily a vehicle for

making connections and learning enough about Japanese society to further

their own careers. Eleven of my sample fell into this category. While a few

seemed preoccupied with finding a Japanese spouse as the first crucial step

to his or her "international career," the majority were simply interested in

acquiring enough linguistic and cultural competence to make them attractive candidates for jobs in the business sector. These ALTs quickly invested

in business cards and were constantly on the lookout for resume-building

experiences and good personal contacts. In the early years of the JET Program, when the bubble economy was still growing, the program drew

many career-minded college graduates. Some did in fact use their JET experience as a stepping-stone to Japan-related careers in journalism,

tourism, government service, and so forth; in rare cases, an ALT would jump ship in April if he or she found a suitable private-sector job. As more

and more JET alumni flooded the job market, however, it became clear that

the JET experience itself was not guaranteed miraculously to open doors.

In the 199os, as Japan has become mired in a recession, fewer participants

single-mindedly depend on the JET experience to set them on their careers.

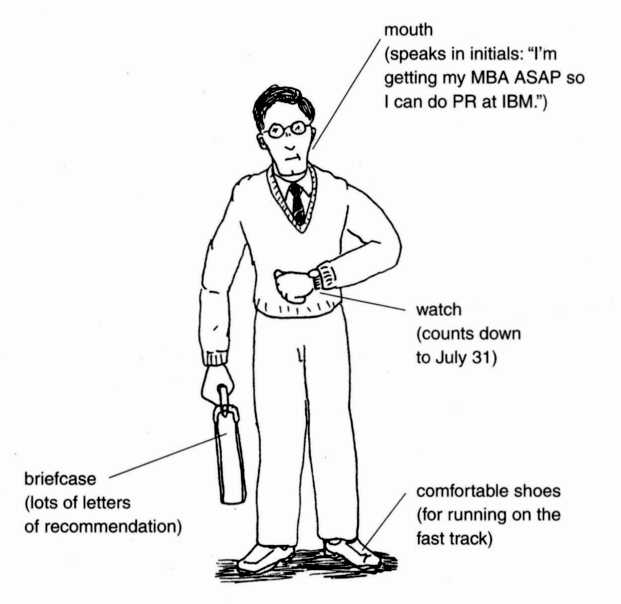

The Yuppie (Homo sapiens money). Distinctive call: "I think that the JET Pro-

gram(me) is the ideal stepping-stone for an upwardly mobile career."

The Nipponophiles

Finally, the smallest number of ALTs interviewed (eight) approached the

JET Program primarily as a learning experience and saw their time in Japanese schools as a golden opportunity to discover an alternative cultural

worldview and to expand personal horizons. They took seriously the challenge of learning Japanese language and absorbing the culture, and they tended to be highly critical of the judgmental reactions of their peers. One

article in the JET Journal captured the flavor of this approach:

Vocal critics of Japan's seemingly slow internationalization process

should maybe conduct a self-cross-examination. Is Kokusaika [internationalization] not a two-way street? I sometimes wonder if all JET participants are as internationalized as they pretend to be. Most of us feel

internationalized because we are anglophones, presently living outside

our home country dealing with people who lack fluency in English and

who have limited experience in overseas travelling. We see the Japanese

as the object of our presence in their own country.... However, how

many of us can look at ourselves and sincerely assert that we are as internationalized as we want the Japanese to be?

Many of us came to Japan without the faintest knowledge of this

country, its customs, language, etc. Many of us only know the basics

about our own country, and our knowledge about the outside world is just as scanty as that of the average Japanese. For many of us, landing a

job in Japan and being the focus of so much attention instantly inflated

our egos which in turn prevents us from remembering that we have

been invited as guests-consultants-by this country. Voicing aggressively our opinions, frustrations, discontents and disapproval will only

contribute to alienation rather than promote internationalization.18

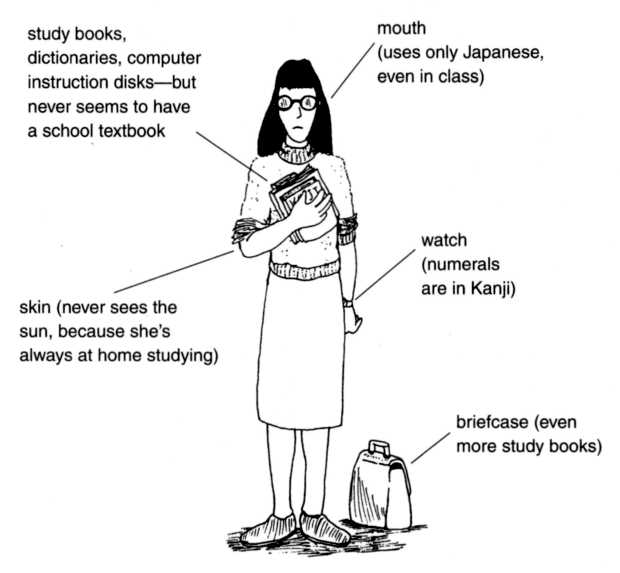

The Nipponophile (Homo sapiens wanna-be). Distinctive call: "I really feel at

home here. The Japanese lifestyle is the best in the world."

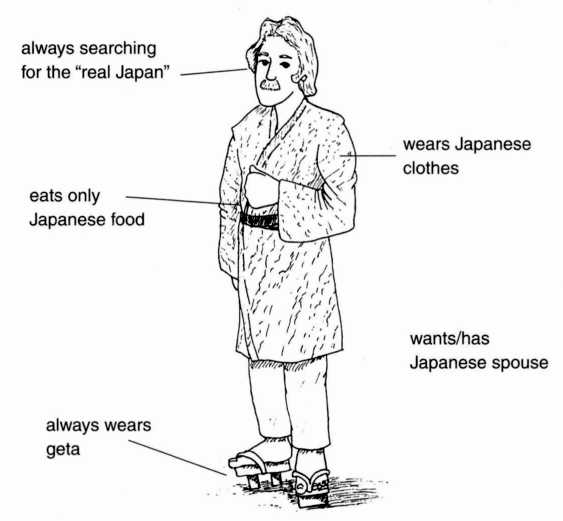

Included in this group were those rare souls who practically rejected their

own culture in the rush to embrace Japanese language and society. They

would complain if their apartment was too close to those of other foreigners, and they avoided most ALT social gatherings. Ironically, they ran the

risk of becoming too acculturated, opening themselves to criticism from

Japanese that they had become a henna gaijin (literally, "strange for-

eigner")-someone who, in a sense, knew too much about Japan and behaved in a manner inconsistent with his or her upbringing.

These groupings roughly describe the range of JET participants. Darin

Price, an ALT in Okinawa from 1 990 to 1993, composed a remarkable set of drawings during his time in Japan that begins to capture some of the diversity of ALTs' reactions to Japanese culture and education in a humorous

way; they have been scattered through this section.

The Loser (Homo sapiens failure). Distinctive call: "The only really bad thing

about this job is the three-year limit."

INTERNATIONAL FESTIVALS

In the fall of 1989 I was invited to an "international cultural exchange festival" hosted by Higashiyama High School. Its objective, as stated in the

program, was "to promote a true sense of international understanding

among the young people who will be our leaders in the Twenty-first Century by inviting members of the foreign community ... to exchange ideas

concerning our different cultures and to promote friendship."

The fundamental plan was simple: to invite as many foreigners from as

many different countries as the organizers could manage. Toward this end the chief organizer, a middle-aged teacher of Japanese language, both obtained permission from the board of education for JET Program participants in the area to attend and used the network of her husband (a university professor) to identify foreign students at local universities who might

participate. The two ALTs based at this school were excluded from much of

the planning process, though their names, pictures, and essays were displayed prominently on information disseminated about the event.