Improving Your Memory (4 page)

Read Improving Your Memory Online

Authors: Janet Fogler

EXERCISE: UNDERSTANDING THE MEMORY PROCESS

Complete the blanks in this scenario to test your understanding of the memory process. Use the words listed below.

Cue

Sensory input

Association

Encoding

Long-term memory

Working memory

Retrieval

When you go to the library and see a lot of colorful books on the “new books” shelf, the component of memory you are using is

You read through the titles and think about whether they interest you. These conscious thoughts occur in the component of memory called

Then you find a book by a favorite author, John Grisham. You take down the book, notice how long it is, read the back cover, think to yourself that it sounds familiar, and decide that you have read this book before. This process is called

The information about the book leaves your conscious thought and goes into the component of memory called

where it may be available for

at another time. When you get home, you notice another of Grisham’s books on your nightstand. This favorite book serves as a

to remind you of the book in the library. The connection between the library book and your book at home is called

See |

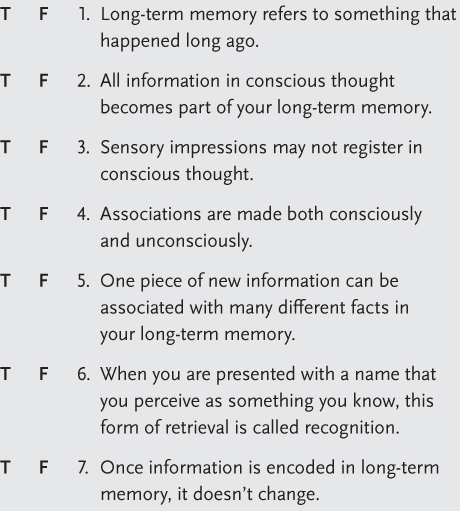

EXERCISE: HOW MEMORY WORKS

True/False. Circle the answer.

See |

Part II How Memory Changes as We Age

6

What Changes? What Doesn’t?

How cruelly sweet are the echoes that start, when memory plays an old tune on the heart!

—Eliza Cook

There are many myths about the inevitability of memory loss as people age. The truth is that most people will not face severe memory loss unless they have a serious illness such as Alzheimer’s disease. But as we age, almost every adult is faced with memory changes that can be frustrating and unnerving. It’s very common to hear people, often starting in their forties, complain about forgetting names, forgetting what they read, misplacing things, or forgetting to do something important. (Just yesterday, one of the authors of this book forgot an appointment.)

Researchers have extensively studied how memory changes with normal aging. Let’s look at what they tell us about what happens to the components of the memory process over time. As we recall from

chapter 2

, the memory process can be divided into three components: sensory input, working memory, and long-term memory.

Sensory input

exhibits little change as people grow older. Unless there is significant vision or hearing loss, people can

register information through their senses in the same way they did when they were younger. For example, Mary can scan the skeins of yarn in a knitting store to select the color she wants for an afghan. She can smell a melon to see whether it is ripe. Max can look through the selection of plants before choosing one for his garden. He can see and hear the birds in the backyard.

Working memory

—the amount of information you can pay attention to at any given moment—is much the same in older and younger people. Mary can think about how much yarn she needs and what color would suit her granddaughter. She can decide which melon to buy for the neighborhood potluck. Before making his selection, Max can think about the design of his garden and the amount of direct sunlight a plant requires. He can recognize a familiar birdcall.

Long-term memory,

information stored in the memory bank, is the component of memory most affected by age. The changes in long-term memory involve the ability to store and retrieve information efficiently.

As you recall from

chapter 3

, the process of storing information in long-term memory is called “encoding.” The following common complaints demonstrate failures to encode information well enough:

• I can’t keep track of where I put my glasses.

• I forget what I was planning to buy at the grocery store.

• After I’ve looked in all of my pockets and checked the car for my cell phone so I can plug it in at night, I find it charging in its usual place, right where I plugged it in an hour ago.

• I can’t remember how to reset the digital clock in my car.

Another problem with long-term memory involves recall. You’ve already learned that retrieval can occur by recognition

(the perception of information presented to you as something you already know) or by recall (a self-initiated search for information from long-term memory). The good news is that most people do not have problems with recognition: they say, “I know it when I see it” or “I know it when I hear it.” In tests that measure recognition of words, older people do as well as or better than younger people. Retrieving information on demand (recall), however, often becomes more difficult as we grow older

Here are some examples of problems with recall:

• I have trouble coming up with names of people I know when I meet them unexpectedly.

• I can’t remember the name of my medicine when someone asks me what I take.

• I don’t remember to turn the ringer back on my cell phone after leaving the movie theater.

• I forgot to water my neighbor’s plants when she went on vacation.

There is another aspect of memory that is so automatic we take it for granted. It’s called “muscle memory.” Tasks that you do repeatedly—such as driving a car, typing on a keyboard, taking a shower, washing the dishes, or tying a shoe—can all be done without conscious thought because of muscle memory. Your muscles remember how to do the task. This type of memory endures throughout life with very little change.

One more piece of good news: people gain knowledge and wisdom with age. Knowledge is defined as a pool of information acquired over a lifetime from both educational and everyday experiences. In tests that measure knowledge, older adults do as well as or better than younger people. Even though it takes greater effort to learn something new, older adults have the experience to determine what new information is important to them.

Wisdom is the ability to see the big picture, to recognize and understand the major themes of life. Through living we gain an understanding of human nature; we become more emotionally resilient; we develop an ability to learn from our many experiences, and we are able to remain more positive in the face of emotional challenges. Memory and experience allow us to recognize patterns and predict outcomes. Through living we learn to adapt to changes and see the truth as having many perspectives.

So, back to the problematic changes in memory discussed above. In

chapters 7

and

8

we’ll explore why encoding and recall become more difficult as we grow older.

7

Problems with Encoding

Our memories are card indexes consulted, and then put back in disorder by authorities whom we do not control.

—Cyril Connolly

It Becomes More Difficult to Pay Attention to More Than One Thing at a Time.

As you age, you may find it harder to attend to two competing activities, thoughts, or conversations. Keep in mind that the amount of information that can be held in working memory is quite limited, so what you are thinking of can be displaced even by your own new thought. External distractions such as a radio playing, someone talking, or a doorbell ringing may disrupt your concentration more now than they once did. The following examples present some common situations and potential solutions.

EXAMPLES

You are in the middle of a discussion at a party when you hear your name mentioned in a nearby conversation. This momentary distraction makes you lose track of what you are saying. You may feel embarrassed and blame your failing memory, but what has actually occurred is that one thought has displaced another in your working memory. This is a common experience, and you can simply say, “Where was I? I lost my train of thought.”

You have several questions to ask your doctor. When she enters the exam room, you have them well in mind. Then she starts asking you about your health. You find that you no longer remember your questions. Remembering what you intend to ask your doctor at the same time that you are answering her questions involves a division of attention. If you go to your doctor with a written list of questions, you will not have to rely on your memory.

You are in the middle of brewing coffee when the thought of an old friend comes to mind. You daydream for a moment about the last time you were skiing together in Vermont. When you leave the ski slope in your mind, you realize you’re not sure how many tablespoons of coffee you have measured. If you count aloud while measuring, you will not get distracted from your task.