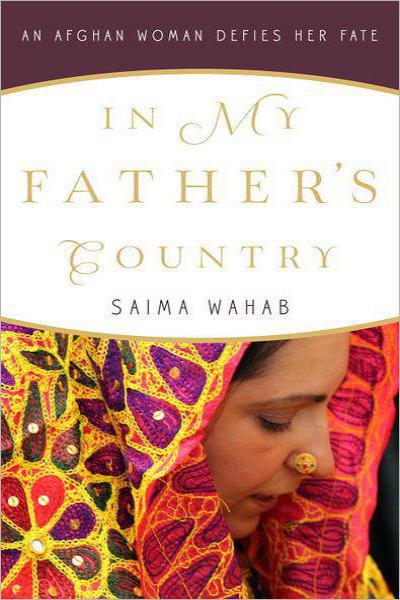

In My Father's Country

Read In My Father's Country Online

Authors: Saima Wahab

Copyright © 2012 by Saima Wahab

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

eISBN: 978-0-307-88496-1

Jacket photography by Vanessa Roberts

v3.1

TO MY FATHER

AND HIS FATHER

Contents

I SHOULD HAVE DIED

when I was five

.

We had just come from Kabul to my grandfather’s village, having left behind everything, including any hopes that our father would walk through the door and end the nightmare of his disappearance. As a child of five, I didn’t understand what was happening in Afghanistan; I just knew that my world had been turned upside down. One day I was in the city, waiting for my father to come home from work so I could climb onto his shoulders while he walked around the house or listened to the radio. The next day, it seemed, I was in a village where all the houses were made out of mud, where going outside meant having an adult open the gate because it weighed at least a ton, and, even if I had been brave enough to venture out, I couldn’t have pushed it open by myself. The shock of what had happened was too shattering, so I slept a lot, sometimes through the whole day, hoping that when I woke up I would be back in the house my father had built with marble from Italy

.

Our grandfather’s

qalat,

as houses in the villages were called, was big, with a mud wall at least twelve feet high surrounding the rooms and the courtyard that we shared with the chickens and the cows. It had three bedrooms, one kitchen, two living rooms, two guest rooms—one for men, one for women—and one big underground room for storage. My sister, Najiba, my mother, and I shared one of the rooms, which was all the way in the back, past one of the living rooms and the kitchen

.

On the day I should have died, I had gone into the bedroom unnoticed, while my mom was busy doing what Afghan women do all day: cooking, cleaning, sweeping constantly. My grandmother was taking care of the animals outside. In the frantic daily routine of village life it was easy to go unseen

.

The Russian jets had no fixed time of the day when they bombed our village. They just did it randomly, and a lot later I would find out that our village was considered a stronghold of the mujahideen, which meant that we got targeted more than the other villages. I remember the constant fear of the sounds of the bombs dropping, whistling so loudly, permanently destroying most people’s eardrums. So that even today, I don’t hear well in my left ear

.

I don’t know how long I had been sleeping before the jets flew over the village, dropping the usual five or six bombs and leaving all of us in the dust before they flew off to the next target. I remember being shaken out of my sleep by what I thought was the roof falling on my head. I was so disoriented and overwhelmed by shock and terror that for a few seconds I couldn’t even stand up to find the door. It was the sound of the walls, made of clay and mud, cracking and crumbling that shook me out of the daze

.

Amid the commotion that always followed the bombardments, Mamai and my grandmother were frantically looking for me. Seeing me come out of the room, dusty and crying, must have given my mother the fright of her life. Villagers and family soon surrounded me, and Mamai grabbed me and checked me all over, as if to make sure that I was really alive. I looked behind me and saw that the room where I had been sleeping had collapsed. A bomb had dropped on the roof, hitting the corner farthest away from where I had been sleeping, and even though it had not detonated, the weight of it had completely demolished the walls and the roof. Everyone seemed amazed that I was alive—to have walked away from certain death, they exclaimed, I had to be the luckiest child in Afghanistan. One of the old ladies told Mamai to make sure she made a sacrifice to God for saving me

.

Years later it dawned on me that that was the first of many moments when I would be protected by some unseen hand, as if there was a destiny I had to fulfill—one that weapons and explosions couldn’t obstruct

.

O

NE

I

was welcomed into this world with gunshots.

In Afghanistan, when a son is born, tradition dictates that the father rushes into the street with his pistol and fires a few rounds into the air to celebrate. My father did this for Khalid, my older brother, his firstborn, as was the Pashtun custom. A little over a year later, minutes after I was born, my father rushed outside with his weapon and did the same. His friends appeared and congratulated him on the birth of another son. My father laughed and said, “Oh no, my beautiful daughter was born today.” But nobody celebrates the birth of a daughter with gunshots. His friends shook their heads at such eccentric behavior. “You will see!” he told them. “I promise that my daughter will prove that she is better than many Pashtun sons, and will do more for her people than one hundred sons combined.”

I CARRY ONE

of my father’s pictures with me always. It is a photograph of him with the three of us—my brother, my sister, and me. It is small, black and white, and bears a collection of tiny holes, puncture marks from the pins and small nails that, over the years, have fixed it to my walls in Kabul, Ghazni Province, Peshawar, and, finally, Portland, Oregon. In his pictures he is a young man with sideburns and big, black-framed eyeglasses, wearing a diamond-patterend crewneck sweater and

listening to the radio, while my brother, sister, and I are draped all over him. My brother, Khalid, who is now roughly the same age our father was when he disappeared, has a collection of sweaters with this same motif, most of them given to him by my sister, Najiba, and me.

In the background you can see our bunk beds pushed against the wall. It is not uncommon for Afghan families to sleep in the same room, and despite my father’s Western tastes, despite his forward-thinking education—he was an attorney—and his radio program that explored Pashtun music and culture, our family was no different, and we all slept in the same room.

Even though I don’t remember when the picture was taken, I cherish that moment. It brings me great comfort when I am faced with self-doubt, and reminds me of what he had predicted at the time of my birth, declaring my destiny to the world.

My father became one of the first prisoners of war during the Soviet occupation, taken from his home by KGB agents when most of the world didn’t even know they were in Afghanistan. I became one of the millions of Afghan refugees of that war at age five, when I still had most of my baby teeth. I have flashes of memories from that nightmare, like taking my pet cat to a settlement of mud houses outside Kabul, leaving her in the center, hoping someone would take care of her because we had to flee the city and couldn’t take her with us. I remember turning around in the car, trying to get one more glimpse of her before saying good-bye to her forever. Even today the sight of people with their pets fills me with sadness.

I remember getting on a donkey to cross the border into Pakistan, and being afraid that it would take off and I would lose the caravan of other refugees, leaving Mamai and Najiba behind with them. The journey to Pakistan took almost ten days. During that time we were at the mercy of kind strangers for food, shelter, and safety. I vividly remember one house where, in the true spirit of

Pashtunwali

, the ways of the Pashtun, they gave us their only two eggs, cooked in real butter. So delicious, I can close my eyes and instantly taste that butter. But after a while, what I return to most is not so much each individual painful memory but an

ever-present feeling of certainty that I would not survive my childhood. I see effects of that overwhelming presence of terror in my childhood in me today, and I know I will feel it for the rest of my life. What is devastating is that there are thousands of us Afghan children, young and old, who suffered through the same journey, and who will forever bear the scars of those years of constant fear.

I DO HAVE

some happy memories from my childhood. One of the very few cherished ones is of my brother, my sister, and me standing at the window on the second floor of our house in Kabul, waiting for my father to drive up in the Soap Dish—what we called his white Volkswagen Beetle—and running down to open the door so he could park, step out, and gather all three of us in a group embrace. He would then place Khalid on his shoulders, and Najiba and I would drape ourselves over his arms as he walked into the house, greeting Mamai with a smile.

On Fridays my father liked to cook big lunches for his family and friends. His lunches were legendary. He had many friends, and they would gather around our huge marble table, which sat thirty-eight people comfortably. Here they enjoyed his excellent cooking and shared many laughs at his expense. Even in Kabul, during the progressive mid-seventies, when women walked around the city in miniskirts and the latest European fashions, men never even entered a kitchen, unless they were searching for their wives to ask them what was for dinner. But my father not only loved to cook, he designed our kitchen to suit his strange methods. Traditionally, Afghan women squat on their heels while cooking because everything—the burners, the food—is on the ground level, but my father realized how much easier it was to cook while standing. So in the late seventies, we were the only family we knew in all of Kabul who had kitchen counters, and Mamai cooked standing up.

On one hot Friday afternoon in 1979, according to my mother, my father was in the kitchen putting the finishing touches on the meal when there was a knock on the door. It was one of our relatives, who’d arrived with a “friend.” The relative asked my father to step outside for a moment. My father paused. He was wearing his slippers. Still, he did not

want to insult his relative, so he stepped outside, closing the door behind him. The KGB had just begun secretly kidnapping and imprisoning people who spoke out against the Soviet Union’s covert involvement in the Afghan government. My father was among the first to openly talk about the danger the Soviet presence in Kabul presented to Afghanistan. On his radio show, he announced to his listeners that the Soviets had arrived in Afghanistan with no good intentions. He let everyone know: They wanted to destroy the country of the proud Pashtun nation.