In My Father's Country (48 page)

Read In My Father's Country Online

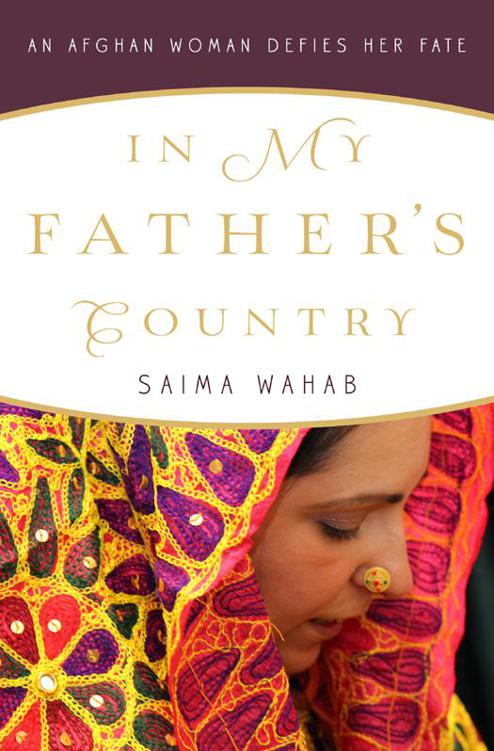

Authors: Saima Wahab

I didn’t need any persuasion. I was emotionally drained from my encounter with the old man, and felt this chance to try to make things right for both the Afghans and the Americans was a godsend. The burden of my desire to bridge my two cultures, a burden that I had been carrying for years, suddenly felt twice as heavy. I would have done anything to make it lighter or at least more manageable. It was not part of my job description, but again, there was no question in my mind that I would meet with the general.

Over the next week, I met with the general several times, sometimes while grabbing a bite at the chow hall, where we couldn’t talk about

why

he was there but could talk about cultures. I wanted to provide him with a cultural background to his investigation so that he could see that the soldiers had done everything right according to their tactical guidelines but had done things completely wrong inside of the bubble of Afghan culture. If he only looked at it as an army mission in isolation, it might be perfectly executed, but if he looked at the raid happening in real time, in a real Afghan village, it was done very wrong. These unofficial “talks” were followed with official meetings at our office in the TOC, where I gave him three recommendations for any future raids. He didn’t give me any indications of whether or not he would take my advice or throw the paper he was writing on into the recycling bin to be destroyed with all the other secret documents that were burned by one of the S-2 soldiers when the bin was filled.

The general left and I continued preparing for my brief and the next mission. The highs and the lows of being at war had made me constantly aware of my emotional fragility, as well as that of the soldiers around me.

With that awareness the burden to do my part in the mission became more challenging and consumed even more of my time. It was common knowledge that HTT had office hours to match those of the TOC office hours, meaning we were there until midnight or later. But not everyone was at the office every night. For personal protection, when either Audrey or I was there alone, we would lock the doors and only open them to people we knew or were expecting. On one of those nights, I was alone in the office putting some finishing touches on a product that was being released the next morning. I had

Seinfeld

playing on low volume on one of my computers while I worked on the other one. Watching it instantly took me back to my living room in Oregon, sitting there with Najiba, laughing and drinking tea—those thoughts alone were an incredible stress releaser, something I needed lately more than ever.

I was sitting there typing when suddenly a rock hit the side of the wood structure of the office. I must have jumped up three feet. My heart pumped like I had just run a marathon, and my face felt cold and numb. The first rock was followed by another, and then another, coming in quick succession, not giving me time to move, even if I could have. This went on for a few minutes, but it felt like hours. There was no shortage of rocks—they covered the ground of the whole base. At first I thought it could have been one of the soldiers playing a prank, and I was ready for the knock on the door. The knock never came, and after three or four minutes, there was dead quiet.

The side that the rocks were being hurled from faced the olive orchard (rumored, of course, to be haunted), which was one of the main ways to get to the local interpreters’ living section. Was it the ghosts of the past trying to scare me, or was it one of the local interpreters, carrying out an order from outside elders in retaliation for taking the villagers during the raid? For the first time, I didn’t feel secure even inside the wire.

I never found out who threw the rocks, if it was one person or ten. That night, I called the guards on duty in the TOC to see if any of them were available to walk me to my room. It was dark and I was shaken to my core. I knew in my gut—and I have always relied on and trusted my gut—that this was like a public stoning for a crime that could have

resulted in my death had I been caught outside the protection of the Americans. When I told Audrey what had happened, she made me promise not to stay too late at the office and to make sure that I had my weapon with me at all times. After that, I never went anywhere without my nine-millimeter, not even to the bathroom. I had to prepare myself for the very real possibility that I could be shot and killed by someone I might even know on the base.

Would I be able to shoot another human being to death to protect my own life?

This suddenly became a real question, flooding me with an anxiety and a terror I knew I would feel the effects of for years to come.

LIFE IN SALERNO

went on. Half of the team were on missions at any given time. The other half stayed behind finishing up products and briefs, attending brigade meetings and working groups. We took turns going to each, bringing back the highlights to share with the rest of the team. I usually went to the morning battle update brief because it was early, and I could never sleep in no matter how late I went to bed. I would grab my coffee from the office and run to the BUB, where if you were late there was standing room only.

One day, almost a month after the general investigating the night raid had come through Salerno, I went to the BUB early enough to get a seat and was halfway done with my coffee by the time the commander and the command sergeant major walked in with theirs. Everyone stood up, then sat back down once the commander was seated. The BUB began and I was taking short notes to be shared with the rest of the team when a slide came up on the projector that was usually an update from one of the other U.S. elements in the area. The slide presented the commander with information on the missions of the previous day. Once done with that slide, the staff sergeant briefing the commander said, “Sir, we have an update about the investigation as well, followed by a division-wide FRAGO.”

I sat up straight. He went into the findings of the investigation, which was classified information, only to be shared on a need-to-know basis. The division-wide FRAGO, an order for all the soldiers in the region,

without exceptions, listed my three recommendations to the general. When I had talked to the three-star general, he had asked for recommendations, but FRAGOs were not recommendations. They were orders, not to be questioned but to be followed, word for word.

Seeing my cultural guidelines up on that slide, I was overwhelmed by a feeling of total serenity. Lately, I had been missing my American life a lot. I had been feeling restless, and the effects of my being harassed and symbolically stoned had worn my nerves thin. And, although I felt validated when talking to military personnel about the human terrain of their areas of operations, as they hung on my every word, I did not feel that I had achieved the peak of my professional life. I had stopped being nervous when I was giving advice to Mike or any other commanders in a room full of his officers and soldiers, because I knew I possessed the knowledge they needed to succeed.

But this was different. This was a testament to

who

I had become. I had taken the first significant step toward bridging the two cultures so dear to me, each in its own right. Oh, I knew that I was nowhere near completing my personal mission, but I saw a milestone, and it was up on the projector. My goal truly was a lifelong endeavor, but for the first time, it was not as overwhelming as it had seemed before.

I had come back to my father’s country as an interpreter, one who only spoke for others, much like a puppet. Five years later, I was speaking for myself, for my people, to my people, and my words were being turned into orders to be followed long after I was gone.

This was an achievement of personal aspiration for which I would have given up anything, even my life. I had thought that I kept coming back to Afghanistan to better understand the Afghan people, when all along the goal was even more personal. I now knew why my father had chosen death over life as my father, and I forgave him his choice because I finally understood.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I remember when I first learned to speak enough English to tell bits and pieces of my life story to friends. They would say, “Saima, you need to write a book.” It took me a long time to write it out for others, and I would not have done so if not for certain people. Their support is what gave me the courage I needed to complete this painful and at times almost unbearable task. Every moment of agony was worth it.

Pashtun men have a bad reputation in today’s world, and it saddens me because I know I would be in a completely different place if it weren’t for the two most important men in my life, my father and my grandfather, both very proud Pashtun men who possessed pride and courage only found in folklore today. I want to pay homage to them both. It was my father’s ultimate sacrifice and my grandfather’s unfailing perserverance to keep his promise to a lost son that kept me going when giving up would have been so much easier. I will never forget.

My sister and I differ in so many ways from each other, and although I know she didn’t, and doesn’t, agree with everything I have done over the years, I know that she always has my back. Knowing she stands with me and behind me is the reason I am able to be who I am. Najiba, you know you are the best little sister I could ever have asked for, and you know that without you I would never have done any of the things worth writing a book about.

I want to thank Mamai, but more than thanking her, I want to apologize for all the suffering I have caused her over the years. I know we started off at opposite ends, but things have worked out as I had envisioned. Today you are exactly the mother I have always wanted, and I hope I am, if not exactly, then at least a tiny bit the daughter you hoped I would be.

I am grateful for my brother, Khalid, for being the best brother in Afghanistan, for not beating me up when all of his friends were beating up their sisters. You might even be the best brother in the whole world for not repressing me, for letting me be who I am, and for standing up for me when I needed you to do so. I am most thankful to you for those times when you didn’t necessarily agree with what I was doing but still stood up for me. You not only share our father’s love of argyle sweaters but you are also the breathing reminder of him in our small family.

Kabir, you came into my life and took my sister from me. That fact should have been enough to make me dislike you, but you have been the kind of caring and forgiving brother-in-law that makes it impossible to stay mad at you. During the process of writing this book, at times I know I was unbearable. Not being related, I know you could choose to avoid me. You took all of it head-on, and I am thankful to you for being there for me and my family.

I want to say a prayer and acknowledge the ultimate sacrifice that our men and women of the Armed Forces made in the war in Afghanistan. Nothing I say here could accurately convey the debt and gratitude I feel for your sacrifice. May your souls rest in peace and may God give your families the courage to see and remember your heroism in their time of pain.

I want to thank all my friends (and you better know who you are!) for putting up with my PTSD, temper, and just plain difficult personality. I know I have not been the easiest friend to have and I am thankful to each one of you for your support. I hope you realize that you’ve made me mellower, or maybe you’ve just gotten better at dealing with my temperament. Either way, I am deeply grateful for our friendship. You have become my extended family that the Afghan in me needs.

Thanks to Karen Karbo for helping me put pen to paper.

And, last but not least, I want to thank my editor, Domenica Alioto. I know I came to you with a mess, and you turned it into a story that I am proud to tell. I could not have done it without your patience and guidance.