In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens (46 page)

Read In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens Online

Authors: Alice Walker

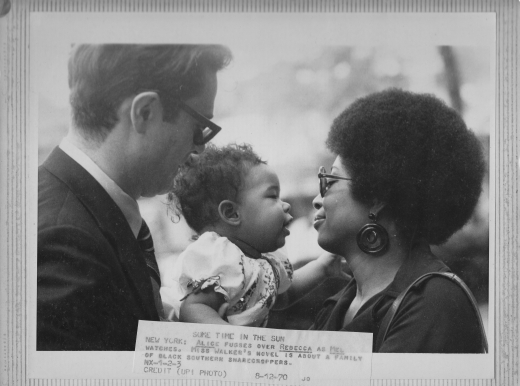

Alice and Melvyn with their daughter, Rebecca, who would also grow up to become a writer, in 1970. Alice had just published her debut novel,

The Third Life of Grange Copeland

, which garnered significant praise and prompted these perceptive words from critic Kay Bourne: “Most poignant is the relating of the lives of black women, who were ready and strong and trusted, only to so often be abused by the conditions of their oppressed lives and the misdirected anger of their men.” Alice characterized it as “an incredibly difficult novel to write,” since it forced her to confront the violence African Americans inflicted on each other in the face of white oppression.

Alice and her partner of thirteen years, Robert L. Allen, a noted scholar of American history, pose for a portrait. The picture was taken at a celebration the couple hosted after the publication of

I Love Myself When I Am Laughing

, an anthology of Zora Neale Hurston's writings that Alice edited.

Walker being taken into custody at a 1980s demonstration against weapons shipments sent from Concord, California, to Central and South America. Her shirt reads: “Remember Port Chicago.” This is a reference to an explosion that killed hundreds of sailors stationed in Concord during World War IIâmost of them blackâwhile they were loading munitions onto a cargo vessel. Walker has remained a dedicated political activist since the 1960s, when she returned to the South after graduating from Sarah Lawrence to help register black voters. Recently, she was arrested with fellow California-based author Maxine Hong Kingston in Washington, DC, during a protest against the U.S. invasion of Iraq. “My activismâcultural, political, spiritualâis rooted in my love of nature and my delight in human beings,” Walker explains.

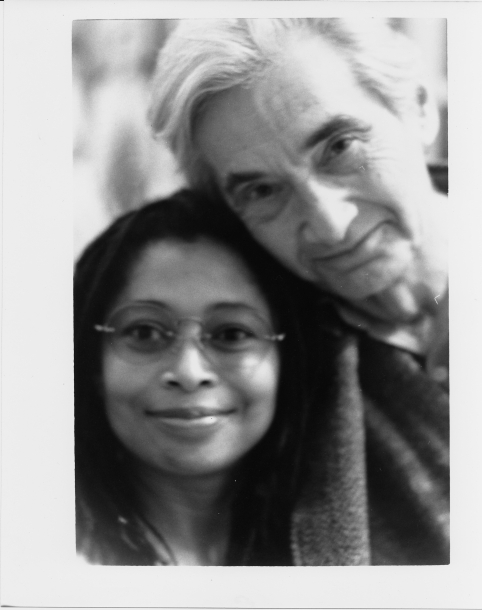

Walker with celebrated historian Howard Zinn, who taught one of her classes at Spelman College, in the 1960s. Walker developed a lifelong friendship with Zinn and considered him one of her mentors. The two shared a passion for political activism and a desire to shed light on the conditions of the oppressed. “I was Howard's student for only a semester,” she says, “but in fact, I have learned from him all my life. His way with resistanceâsteady, persistent, impersonal, often with humorâis a teaching I cherish.”

A photograph of Walker taken in 2007 at a ceremony for her dog, Marley, and her cat, Surprise. “Marley appeared,” she says, but “Surprise slept through it!”

Walker at her country home in Northern California, where she has lived since the early 1980s. “What attracted me to this part of the worldâNorthern Californiaâis really the resemblance to Georgia that it has,” she once told an interviewer. “This has been a very good place for me,” she went on, “a very good place for dreaming.”

Walker writing on the front porch of her California home. She has lived in many different places throughout the worldâincluding Africa, Hawaii, and Mexicoâand finding a place to write has always been a matter of utmost importance for her. She once said that “books and houses” are what she “longed for most as a child.” Years after her tenant farming childhood, Walker is happy to have a place she can truly call home.

The essays, articles, reviews, and statements in this collection were written between 1966 and 1982. For her early reading of some of them and discussing her thoughts about them with me, I thank my friend June Jordan. For gathering them together and insisting I publish them as soon as possible (five years ago), I thank my friend Susan Kirschner. For her help in reading the essays and suggesting an order for them (other than the one in which they now appear), I thank Elizabeth Phillips. For creating the order in which they do appear, I thank my editor, John Ferrone. For his way of making the creation of a writing space for me the first priority wherever we lived, I thank my former husband and friend, Mel Leventhal. And for her help in gluing me to Life, present and future, I thank our daughter, Rebecca Leventhal. For their active pride in me when I was a child (which translated into quarters and dollars and from Miss Bessie an old velvet-covered Victrola), I thank the good “ladies” of the church, to whom I would still turn in looking for justice. And for the three magic gifts I needed to escape the poverty of my hometown, I thank my mother, who gave me a sewing machine, a typewriter, and a suitcase, all on less than twenty dollars a week. My father's gifts, for which I deeply thank him, are daily surprises: my love of naturalness, the tone of my voice, my very face, eyes, and hair. For his expressed pleasure in sharing adventures and making me happy (“hitting the road with just our music and our lunch money”), I thank my much cherished companion, Robert Allen.

In my development as a human being and as a writer I have been, it seems to me, extremely blessed, even while complaining. Wherever I have knocked, a door has opened. Wherever I have wandered, a path has appeared. I have been helped, supported, encouraged, and nurtured by people of all races, creeds, colors, and dreams; and I have, to the best of my ability, returned help, support, encouragement, and nurture. This receiving, returning, or passing on has been one of the most amazing, joyous, and continuous experiences of my life.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

The author wishes to acknowledge the following for permission to reprint the material listed: Marilow Awiakata: her poem “Motheroot,” from

Abiding Appalachia: Where Mountain and Atom Meet

, St. Luke's Press, Memphis, 1978; Doubleday & Company, Inc.: “Now That the Book Is Finished,” from

Good Night, Willie Lee, I'll See You in the Morning

, by Alice Walker, copyright © 1979 by Alice Walker, A Dial Press Book; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.: “Women,” copyright © 1970 by Alice Walker, “Be Nobody's Darling,” “Mysteries,” “Reassurance” copyright © 1973 by Alice Walker, all from

Revolutionary Petunias and Other Poems

, “Once,” from

Once

, copyright © 1968 by Alice Walker; Harold Ober Associates, Inc.: poems by Langston Hughes: “God to Hungry Child,” copyright © 1925 by Langston Hughes, from “Good Morning Revolution,” copyright © 1932 by Langston Hughes, “Revolution,” copyright © 1934 by Langston Hughes, “Tired,” copyright © 1931 by Langston Hughes; Liveright Publishing Co.: “From an Interview” (as “Alice Walker,” copyright © 1973 by Alice Walker), from

Interview with Black Writers

, edited by John O'Brien, copyright © 1973 by Liveright Publishing Co.; New Directions Publishing Corp.: from

In Cuba

, by Ernesto Cardenal, copyright © 1974 by Ernesto Cardenal and Donald D. Walsh; The New York Times Company: “The Almost Year,” © 1971 by The New York Times Company; Random House, Inc.: from

Angela Davis: An Autobiography

by Angela Davis, copyright © 1974 by Angela Davis; The University of Illinois Press: “Zora Neale Hurston: A Cautionary Tale and Partisan View,” Foreward to

Zora Neale Hurston: A Literary Biography

, by Robert Hemenway, copyright © 1977 by The Board of Trustees of the University of Illinois.