In the Catskills: A Century of Jewish Experience in "The Mountains" (63 page)

Read In the Catskills: A Century of Jewish Experience in "The Mountains" Online

Authors: Phil Brown

Tags: #Social Science/Popular Culture

“Well, if I were here,” Jeremy says. He speaks as if from a great distance. “If I had something to say.”

Elizabeth blinks. It is as if he were asking her, And who are you? Of course, she is no professor. There is a feeling with Cecil, and even more with Beatrix, of a kind of brisk and academic egalitarianism, as if in their house anyone can say anything. Elizabeth forgot for a moment that it is only they who really can say anything. Cecil is very strange. And his wife, too, with her strange sleeveless tunic of a dress, her loose hair, her Oxford ways. Knowing Hebrew without going to shul. Cecil and Beatrix cast a kind of spell. All the rules are different with them. It strikes Elizabeth that Beatrix and Cecil are so different from the Kirshners she lives with that she doesn’t even disapprove of them. Ironic that last summer she was appalled along with all the other Kirshners that a woman from shul was seen in trousers in the park. But if Cecil’s wife drove her car down Main Street on Shabbat, Elizabeth wouldn’t be shocked at all. It really would be quite natural for Beatrix; it wouldn’t be offensive in the same way.

“But what do people do here?” Beatrix asks again. “What is there to do? Besides eat rugelach, of course.” She flashes a smile at Regina, who looks stoic.

“Go hiking,” Cecil says.

“Play badminton,” Elizabeth suggests.

“Oh, badminton, I love it!” Beatrix cries with real enthusiasm. “I’m appalling now, but I used to play at home. It was my only game at school, and I used to practice madly, to show I was proficient in

some

thing physical, because I was hopeless for their ghastly hockey teams. I’ve found a net, you know, in the cellar, and we could set it up in back. It’s still light out. We could chalk the ground. I could do it this afternoon while you’re up there praying.”

“You could wait till Sunday. Then I’ll help you,” Elizabeth says, alarmed at the thought of causing Beatrix to transgress.

“Not at all,” Beatrix says. “Division of labor. Leave it to me. Leave it to the secular arm.” And she stretches out a sinewy bare arm.

When the long day ends and the evening settles over the trees, the men walk back to the synagogue for services. The women sit in their glider rockers and their porch swings and they look into the fading light and talk. They talk about their children and their husbands and the traffic from the city. They talk about berry picking, the blackberries now in season and the blueberries to come. Then they lower their voices so the children will not hear. They speak of Israel and the hijacking of the Air France flight. The hostages in Uganda. The talk of politics mixes with the scent of roses.

Elizabeth sits with Regina on Cecil’s porch. “Can’t you stay a little longer?” she asks.

“No,” Regina says, “I have to get back to the lab.”

“Tell me about California,” Elizabeth says.

Regina smiles. “Why don’t you come out and see for yourself?”

“Oh, I don’t think I’ll ever have a chance to go to Los Angeles,” Elizabeth says. “Tell me what it’s like to live there.”

“What do you want to know?”

“What’s the Jewish community like?” Elizabeth asks. Her question sounds parochial, but it isn’t meant that way. She asks out of intense curiosity. She wants to know what it is really like to live there, and so she tries to imagine herself in that place, a part of that community.

“We live in the Pico Robertson area,” Regina says. “On a beautiful flat street with palm trees.”

“All lined with palm trees?” Elizabeth asks.

“Yes,” says Regina, and she looks out at the great trees on Maple, and the tiny jagged pieces of sky cut out between the leaves.

“And where do you daven?” Elizabeth asks.

“In a synagogue that used to be a movie theater.”

“No!”

“Really. It’s a grand old movie palace with the lights and the curtains and everything. And the women sit in the balcony. The name of the shul is outside on the marquee. And believe me, there isn’t any coatroom like there is here.”

“No one wears coats?” Elizabeth asks.

“Maybe light jackets in the winter—or a sweater.”

Elizabeth laughs in delight. “You must love it there.”

“No,” Regina says. “I love it here.”

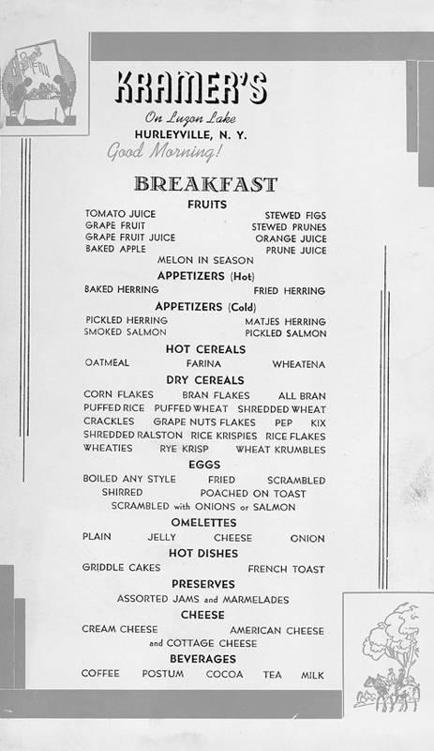

Breakfast menu from Kramer’s Hotel, Hurleyville. C

ATSKILLS

I

NSTITUTE

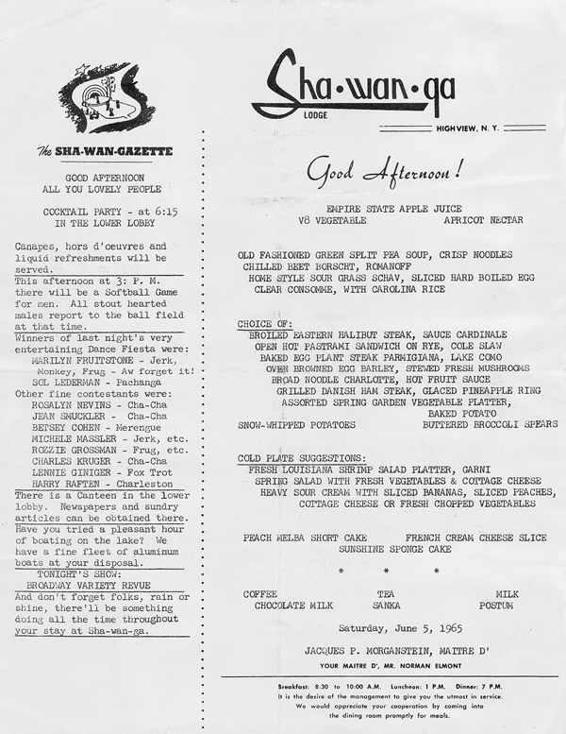

Lunch menu from Sha-Wan-Ga Lodge, High View, 1965. Lunch and dinner menus were often full of activities and entertainment information. C

ATSKILLS

I

NSTITUTE

Dining room staff at Kutsher’s Country Club, Monticello, 1956. I

RA

G

OLDWASSER

Sylvia Brown, chef at Chaits in Accord, 1970s. P

HIL

B

ROWN

F

ood dominated life at the hotels. Huge meals of great variety were the Catskills signature, and the source of much analysis, humor, and deprecation by guests, dining room staff, and comedians. Busing and waiting provided the largest number of jobs for upwardly mobile youngsters.

Sarah Sandberg’s “Eating at the Hotel” comes from

Mama Made Minks

, one of several books she wrote in a very chatty style, almost like serialized magazine articles. This excerpt gives an idea of the richness of the meals both in the dining room and in the napkins that delivered food back to the guest rooms. Sandberg’s furrier family also used the dining room as a place to parade new minks and recruit customers.

Elizabeth Ehrlich’s selection, “Bungalow,” is unique in its focus on eating in bungalow colonies. This is not much of the lore of the Mountains, since the wives were doing all the cooking and were not likely to provide the massive feasts found in hotels. The piece is a chapter in

Miriam’s Kitchen: A Memoir

, a very tender book that follows Ehrlich’s relationship with her mother-in-law, Miriam, who teaches her how to cook while reliving her life experiences in the Holocaust and since. In Miriam’s bungalow, people eat well, all the classic Jewish dishes. Ehrlich recounts an interesting Catskills bungalow colony tradition of collective meals of delicatessen or smoked fish on Saturday night in the casino. At the only bungalow colony where my father ran a concession, I remember well this kind of event. We supplied the food—especially rye bread and pastrami, roast beef, and corned beef that my father sliced at the very last minute—and mixers at a per-person price, and the residents brought their own beer or liquor. This is a wonderful example of how food binds people together.

Vivian Gornick included “The Catskills Remembered” in her book

Approaching Eye Level

, and read it at one of the History of the Catskills Conferences. Gornick recounts the difficulties of being a waitress in the Catskills, where waiters predominated. She portrays the competition among the waitstaff, the tension between them and their guests, and the conflicts they had with the maitre d.’ This is definitely the harder end of the dining room life, but nevertheless it is true to life. For those in the know, Gornick’s fictional names are vividly recognizable—her Stella Mercury employment agency was in really Annie Jupiter’s, a New York City agency that supplied many of the hotels.