In the Sanctuary of Outcasts (16 page)

Read In the Sanctuary of Outcasts Online

Authors: Neil White

Winter

My mother and me (in kilt) in Scotland, 1969.

I stood behind the barricade and waited for a guard to escort me to the visiting room where my mother was waiting for me. She had made the trip alone and, as usual, arrived forty-five minutes early.

During my first year of junior high, my parents divorced. I lived with my mother and my three younger siblings. My mother, perhaps to counteract any ill effects of divorce, reminded me almost daily that I had been chosen for an extraordinary path. I started to believe her. Not just that I could make a difference, but that I was special and had been called to share my gifts with the world. She believed her children’s skills should be showcased at every opportunity. She registered me, as the eldest son, for races and contests and tournaments. A master at bolstering my self-esteem, she often reminded me of the meaning of my name. She would say the words like she was sharing with me my own destiny, “Neil

means

champion.” I believed what my mother told me. And I was certain we would make the world a better place.

Mom started an alternative school for juvenile delinquents in Gulfport. She spent her days giving them the attention and praise and hugs they had missed in their homes. She lauded their talents, whether those came in the form of suggestive dance, graffiti art, or a knack for breaking into locked cars to retrieve keys.

To some, my mother was a saint; to others an enigma. She was on her fourth marriage; she held three graduate degrees; she had lived in twenty-seven different houses during the last three decades and had held no fewer than seventeen jobs. She had launched two magazines, founded three schools, self-published five books, served on

the boards of four corporations. She had started a restaurant, a dress shop, a riding stable, a camp for disadvantaged kids, a nonprofit education company, and a low-income housing project. She had a house in Gulfport, an apartment in New Orleans, and a husband in Oxford. She took risks. She relished the unknown. She loved the limelight. She stood fearless in the face of change and approached her own life as if it were a thrill ride. And I had always wanted to emulate her.

When I arrived in the visiting room, I saw Mom waiting at a table in the back corner. We hugged, and she said, “How are you, baby?” But she didn’t need to ask. She knew I was in trouble again. That’s why she was here.

The last time I was alone with my mother was April 9, 1992, about an hour after the banks had closed my accounts. When I arrived at her house, she tried to hide her dread, but she knew something was wrong. I wouldn’t have been at her house, on her back porch, in the middle of a workday if the news were good. Mom lived in a house that had been handed down through three generations of her family. It was once my great-grandmother Floy’s home. Floy was a teacher and missionary. In 1903, she moved to the Philippines. She educated the islanders about math and literature and God. Floy had retired by the time Mom was born, so Mom became Floy’s student. She instilled in my mother a sense of service and selflessness. In the 1930s, Floy invited people of color to sit and eat at her dining table when integration of any sort in Mississippi was taboo. She fed hoboes who jumped off the train between New Orleans and Mobile. And she passed along lessons to my mother: “If you have an extra dollar,” Floy would tell her, “give fifty cents to someone who needs it more than you—with the remainder, buy a book.” Floy’s rules for living were passed along to my mother on the very spot where we sat on that cool Thursday morning.

With the breeze from the Gulf of Mexico gently rocking her porch swing, I told my mother I was over $2 million in debt. I told her I had no idea how I would repay the $200,000 she had invested in my company. I told her the FBI would be investigating to determine if I had violated any laws. My mother pressed her lips together and

started to cry. She hugged me, fighting tears, and said we would get through anything as long as we stuck together. I left her sitting in a chair on the porch. She put her head in her hands and let the tears flow. She was the strongest woman I knew, but this was too much. She cried for Linda. She cried for Little Neil and Maggie. She cried for me, her firstborn son, who might face prison. She cried because she had no more money to give me. She cried for all that we were about to lose.

Mom reached across the visiting room table and held my hand. Mom, at fifty-two, was still a striking woman, tall and fit, with auburn hair. She was strong and generous. She never once mentioned the money she lost investing in my company. And she still seemed to believe all those things she told me when I was a child. In spite of everything, she still believed in me, and that I would do great things.

“I talked to Linda,” she said. “I’m going to bring the kids to visit as much as I can.”

Stability wasn’t Mom’s strong suit, but no one was better in a crisis. From Oxford to Carville was a twelve-hour round-trip. But Mom lived in Gulfport. The drive to collect the kids, bring them to Carville, and then return home made it a twenty-four-hour ordeal in a single weekend.

Mom took a deep breath and rubbed her hands over the linoleum table like she might be sweeping away crumbs. “Baby,” she said, “what are your plans?”

“I have no idea,” I said. My postprison career plan had disappeared. Linda and I had discussed launching a small publishing venture. She would be the front person, we had decided, and I would work behind the scenes. But now, with an impending divorce, I didn’t have a plan.

“Do you know where you’ll live?” she asked.

Memphis seemed like a logical choice. It was the largest city near Oxford. I would live less than an hour away from Neil and Maggie. Surely I could find a job there.

Mom looked away like she was disappointed. “You need to think long and hard about that,” she said. She put her hands together and leaned on her elbows. “If you live in Oxford,” she said, “you could see them every day.”

I could list a thousand reasons to not move back to Oxford. I reminded Mom that no good jobs existed in that small town, especially for me—an ex-convict who, five years earlier, had alienated so many in Oxford, ended up in bankruptcy, and moved away disgraced. Not to mention Linda, who would abhor the thought of my following her.

Mom swallowed. “You either live in the same town with your children…or you don’t. There is no in-between.” She talked about the reality of a seventy-five-mile separation. “If you build a life in Memphis, you will grow apart from your children. It breaks my heart to think about your living in a place where Neil and Maggie don’t live.”

I told her I would give it some thought over the next few days. She said she would bring Neil and Maggie to visit often, and she would make sure they were here for Kids’ Day—a Saturday when inmates’ kids would be allowed inside the prison for the entire day.

When visiting hours ended we hugged and said good-bye. As she left, a middle-aged inmate asked if I would make an introduction the next time she visited.

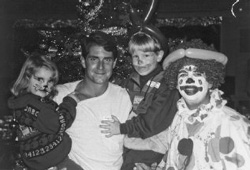

Maggie, me, Little Neil, and inmate Steve Read (in clown suit)

(left to right)

during Kids’ Day celebration.

On a Saturday morning in December, I waited with about forty other inmates for a guard to escort us to the ballroom for Kids’ Day. I was almost giddy about spending the day with Neil and Maggie. For the first time they would be allowed beyond the visiting room. We would be able to spend time together inside the prison, and they would finally see where I slept and spent my days.

The guard who escorted us was overly polite. He said more than sixty children were waiting for us, their inmate fathers. A dozen guards and a handful of inmates had volunteered to run the activities for the kids.

When I walked into the ballroom, I saw Neil and Maggie standing with some of the other children. Maggie wore a denim jumper and a bright red Christmas sweater. Neil was dressed in a hooded sweatshirt and sweatpants. When they saw me, they both ran toward me and jumped into my arms.

Steve Read was one of the inmate volunteers. He was dressed in a clown suit. He set up a station where he made balloon figures for the kids. He made reindeer antlers for Little Neil and a sword for Maggie.

A female guard handled face painting. She painted Maggie’s face like a cat. She painted Neil’s nose red and gave him a huge circus-clown smile.

An inmate band of four Mexicans played the same song over and over. Two counterfeiters put on a puppet show for the kids. Even in prison, there was a carnival atmosphere. Throughout the morning the

guards and inmates organized cake walks, a beanbag toss, and dizzy-izzy contests. Bean, the chubby Mexican inmate, took photographs of the inmates and children.

All the guards were exceptionally nice on this day. And I appreciated it. In fact, they served us. As we sat at tables with our children, guards brought us platters of hamburgers and hot dogs. They poured lemonade and mint-flavored ice tea from a glass pitcher.

After lunch, the kids were told to rest before the outside games began. Neil and Maggie wandered around the ballroom. Neil found one of the patients’ bingo cards and asked if we could play. It was a specially designed card where chips weren’t necessary. Patients who had lost feeling in their fingers couldn’t handle the small chips. I imagined Ella had used this card on occasion. She loved bingo.

Then Neil saw the grand piano. He had just begun to have an interest in playing. I asked a guard if it was all right for the children to play it. She said yes. It was a full-sized grand piano, but it was in terrible condition. The ivory had fallen off some of the most-often-used keys in the center. As Neil and Maggie put their small fingers on the piano keys, I thought about how many leprosy patients might have placed their fingers in the same place. When the piano was first purchased, before there were medicines to stop the progression of the disease and when finger absorption was commonplace, sometimes two patients would learn to play a song written for a single pianist. They learned to play the songs as duets so they would have enough fingers between them to play all the notes.

Rain started to fall, and the outside activities were postponed. But the guards had a backup plan. They had rented a movie,

Free Willy

. As the guard slid the VHS tape into the deck, the kids took their places on the floor around the large television. An inmate whispered in my ear. “What kind of fucked-up people would show a movie about an imprisoned whale to a bunch of kids visiting their dads in prison?”

Steve Read, still in his clown costume, added, “

Free Daddy

must have already been checked out.”

Two hours later, when Willy jumped over the barrier and swam away, the rain stopped, and the kids were allowed thirty minutes inside the inmate courtyard—and then, for a few minutes, inside our dorms. This is what Neil and Maggie had been waiting for. They didn’t understand why, during their visits, they couldn’t play in the inmate recreation yard. Maggie, particularly, didn’t understand why she couldn’t come to my room. Today, as I promised, they would play on our basketball court, run around our track, and try out my prison bunk.

We walked downstairs past the post office and the leprosy patient canteen. Ella was just making her last run of the day. I stopped to introduce Neil and Maggie to her. She smiled and held out her hand, but they had no interest in talking. They were impatient and didn’t want to miss anything, especially the slam dunk promised by the six-feet, seven-inch inmate named Slim. Neil and Maggie ran toward the inmate side. I shrugged. Ella understood. For her to watch sixty young children running through the colony corridors must have been surreal. But she seemed happy to be in the middle of it. I left her sitting there like a boulder in the middle of a stream of children.