In the Sanctuary of Outcasts (14 page)

Read In the Sanctuary of Outcasts Online

Authors: Neil White

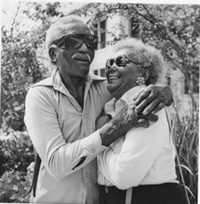

Ella Bounds meanders down the corridor.

The prison was quiet and cool the day I turned thirty-three. My mother sent me several books, and my father put $100 in my commissary account. Neil and Maggie sent homemade birthday cards.

On the same day, Doc also got some good news. He was awarded a U.S. patent for his medical injection device designed to cure impotence. The one-page document contained an illustration of the injector with a curved base for a snug fit around the penis. But, to me, that wasn’t the most interesting part. The document listed the “inventor” as Victor Dombrowsky. It even listed his federal inmate number.

Doc was a brilliant physician and innovator. But he didn’t pursue medical ventures unless there was potential for great profit. When it came to money, Doc went for the jugular. He dispensed heat pills to the obese and invented a cure for impotent men. No two groups would be more willing to pay any price to be cured.

Thirty years earlier, another trailblazing physician lived at Carville, Dr. Paul Brand. Dr. Brand was the antithesis to Doc.

Brand, the son of missionaries, grew up devoutly religious in India. After completing his medical training in Britain, Dr. Brand returned to India to follow in his parents’ footsteps. When he first encountered leprosy patients, he was reluctant to treat them for fear of contagion. But then he realized that few, if any, qualified physicians worked with the “lepers.” Their care was provided by religious zealots or monks.

With the help of his faith, Paul Brand overcame his own fears. During the time he worked in India, his knowledge of, and skills in, the orthopedic aspects of the disease surpassed any physician’s before

him. He developed groundbreaking techniques for restoring nerve-damaged hands. But it wasn’t always appreciated by the leprosy patients. His successful surgeries created a financial hardship. Begging was their only source of income. With corrected, functional hands, their ability to collect alms was greatly diminished.

After two decades of selfless service in India, Dr. Brand accepted a position at Carville.

The patients called him “Saint Paul.” Brand treated each patient with the utmost respect. He wanted to help patients regain their dignity, as well as repair their bodies. One Carville patient said that Dr. Brand touched her foot as if he were “handling a delicate, but broken instrument.”

Better than anyone else, Brand understood the curse of insensitive limbs. Sores on numb feet went undetected. Injuries to anesthetized hands could go unnoticed for weeks. He had perfected techniques and surgeries to repair his patients’ damaged hands and feet.

In the years before his arrival, amputations at Carville were commonplace. But in the first seven years he served as lead orthopedic surgeon, not a single amputation took place.

Ella rolled into the cafeteria wearing her prosthetic legs.

“You wear those because it’s my birthday?” I asked.

Ella knocked on one of her artificial legs and smiled. “How old you is?”

“Thirty-three,” I told her.

“Jesus that old when he rise up,” she said.

All good southerners knew Jesus had died at age thirty-three. I figured Ella would recount the lessons she had heard in church about the thirty-third year being one of change and transformation for Christians, but she didn’t.

So I told her a story my mother recounted on birthdays. It was my favorite family story. A great tale of our Scottish heritage.

The MacNeil clan chieftain, the story went, was feuding with another clan leader over ownership of an island. Rather than risk widespread

death and injury, the two agreed to settle the issue in a competition. The two chiefs would race from the mainland to the island, and the man who first put his hand upon land would claim the isle for his clan. In the early morning fog, the two men set out in their open boats. The race was a dead heat until the very end, when the opposing clan chief inched ahead. At the end of the race, with MacNeil a few boat lengths behind, the island looked lost for the MacNeils. As the other chief stepped out of his boat in the shallow water near shore, the MacNeil chieftain removed his blade and severed his right hand. He picked up the bloody stub and hurled it onto shore, winning the island for the MacNeils.

I loved hearing the story as much as my mother loved telling it. Afterward, she would point to the red hand on the coat of arms that decorated our wall and recite the Latin motto printed under the crest—

Vincere Vel Mori

. “To Conquer or Die.”

“That ’splains a thing or two,” Ella said.

Just as I finished telling the story, I looked at Ella’s legs, and I realized she might not want to hear a story about a man who performs his own amputation. I tried to change the subject.

“Do you remember your thirty-third birthday?”

“Sure do,” she said. “Got these.” Ella tapped on her prosthetic legs again. “Looks like they was made for a white woman.” Ella laughed, but she was right. The light color didn’t come close to matching her skin.

Ella didn’t want to miss anything. When she was young, she loved to run and dance. She stayed on the move. And over the years, her legs were badly damaged, but Ella didn’t feel the pain. In the late 1940s, when she turned thirty-three, her legs were taken away just above the knee. Paul Brand arrived at Carville twenty years too late for Ella.

Her surgery forever altered the way she looked and the way she lived. Her body was transformed. And for nearly fifty years, she had meandered the halls in her hand-cranked wheelchair—welcoming new patients, visitors, even inmates; taking drinks to the residents who couldn’t make it to the canteen on their own; smiling at everyone. I couldn’t imagine her any other way.

At thirty-three, Ella started over.

Stan and Sarah, the blind couple who tapped their way through the corridors.

During the five months I’d been at Carville, I had talked to almost all the patients who ate breakfast in the cafeteria. I’d made some good friends. However, I had never approached Stan and Sarah, the blind couple. I couldn’t convey with a smile or a nod that I wasn’t a dangerous criminal. They couldn’t see me, but I had watched them as they walked arm in arm around the colony. Most blind people tapped their cane lightly, but Stan slapped his stick against the floor and walls to send the vibration past his numbed hand to his arm and shoulder. I could hear them coming down the corridors before I ever saw them. They maneuvered fairly well in the cafeteria, at church, and in the hallways, but on occasion, Stan became disoriented.

After lunch one afternoon, when I was alone with them in the patient cafeteria, Stan, with Sarah on his arm, tapped his way around the tables and chairs. They had almost made it to the door leading to the leprosy patient dormitories when he veered off course. Stan ushered Sarah into an empty nook. A coat closet. I watched for a moment. I noticed the confusion on his face. He turned and guided his wife into a wall. Then, he turned, and tapped his way back into the corner again. I couldn’t stand it. I walked over and softly gripped his tapping arm.

“This way,” I said, gently tugging Stan’s elbow, leading him toward the exit.

“Don’t touch me!” he snapped. “We don’t want your help.”

Stan jerked his arm out of my grasp. I stepped back into the hallway. Stan gathered his bearings and led his wife out of the alcove.

They tapped their way to the exit and turned left toward their dormitory. I stood alone in the cafeteria listening to the sound of his stick against the concrete. It faded away, and I sat down.

Stan and Sarah couldn’t see me. They didn’t see my expression. They didn’t know I was trying to help. All they knew was that I was a convict. They were afraid of me. And for the first time, I understood how the leprosy patients must have felt when people were afraid of their touch.

Me in Oxford, Mississippi, just after the fall that left scars on my forehead, 1961.

As I immersed myself in reporting on the patients, my reaction to their deformities changed in ways I never could have imagined. The shortened fingers of a patient from Trinidad were perfectly smooth and symmetrical. At times when I saw him talk and gesture with his miniature hands, he looked like a magical being who didn’t have to bother with human traits like fingernails that needed to be cleaned or clipped or groomed. His hands were nothing short of perfect. For him.

I had grown accustomed to Harry’s distorted voice. When he would reach deep into his front pocket to retrieve his wallet and say, “My mudder taut me to do dat,” I heard him clearly. His specially designed Velcro shoes fit his unique feet in a way that made standard shoes seem like restrictive boxes. His tools—from a device to help him button his shirt to the utensils he used to eat—didn’t seem unusual anymore. And his incomparable hands. The white skin under his palm met the dark skin from the back of his hand to form a seam where his three middle fingers once existed. His hands were one of a kind. White circles covered the knuckles where his left thumb and index finger once were, as if the pigmentation had been rubbed off. I imagined no other man or woman on earth had hands quite like his. The more I saw them, the more comfortable I became.

Ella was no different. I couldn’t imagine her without her wheelchair. The only time she seemed odd was when she put on her prosthetic legs. I was so accustomed to the way her dress fell across the front of her chair, the way her hands gripped the handles of her cranks, and the way her wheelchair wobbled as if it were the seasoned

gait of any other nondisabled woman in her eighties. Her deformities disappeared.

I had experienced this before—at the other end of the spectrum. When I dated the homecoming queen at Ole Miss, I was at first astonished by her loveliness. To see her walk across the Ole Miss campus, a beauty among some of the most beautiful women in the world, would make me light-headed. At times, I couldn’t believe she was attracted to me. I watched people stop to stare. Men couldn’t help turning their heads. Sometimes women did, too. She possessed the kind of physical perfection that seemed almost unfair. But as our relationship progressed, my awe of her waned. Her appearance had not changed, but I ceased to be dizzy when I saw her. Her perfect nose and lips and hair and eyes were as mundane as the features on my own face.

Intimate, prolonged contact, it seemed, made everything commonplace. Beauty

and

disfigurement disappeared with familiarity. Beauty queens became ordinary; leprosy patients did, too.

I had spent my life surrounding myself with beautiful people. And I made certain no one ever recognized my shortcomings. A childhood accident left two oblong scars in the center of my forehead. Just after my first birthday, while my babysitter talked on the phone, I tumbled down five concrete steps at Avent Acres apartments in Oxford (where my family was living while my father attended law school at Ole Miss). The injuries weren’t the kind of cuts that stitches could repair; the rough edge of the concrete scraped the skin off my forehead. My mother called it concrete burn. A physician covered the injuries with gauze and sent us home, but a week later, he pulled off the gauze and with it came the two scabs. Two oblong scars now dominated my forehead.

Until I was almost ten years old, I was oblivious to the peculiar marks on my forehead. But when I finally did recognize their oddity, I went to extraordinary lengths to hide them. I kept my bangs long enough to cover my forehead, and I constantly pressed my hair down to ensure the scars were hidden. I lowered my head on windy days so no one would get a glimpse if a strong gust came along. During

swim team practice, I was careful to emerge from underwater perfectly perpendicular so my hair would never be swept back to reveal my flaw. During school pictures, photographers would come at me with a comb or brush, but I would press my hands over my bangs and tell them I liked my hair this way.

At home, locked inside my bathroom, I would push my hair back and stare at the unsightly scars. Keeping my forehead constantly covered was inconvenient, but the alternative was unthinkable. Others might find the blemishes abnormal. Maybe even repulsive. In front of the mirror, I resolved I would never let anyone see my damaged skin.

In the summer of 1980, after I made good grades my freshman year at Ole Miss, my father arranged to have the scars repaired by a plastic surgeon. During the preliminary exam, the doctor pinched and prodded the scar tissue and assured me that when he was finished the hairline scars left behind would blend in perfectly with the wrinkles that formed in my forehead when I raised my eyebrows. The procedure took less than thirty minutes. I was awake the entire time. When he finished cutting out the oval scar tissue and pulled the skin together with the final sutures, he gently pressed a piece of gauze over the incisions.

“That isn’t going to stick to the scab, is it?”

He held up a tube of ointment and instructed me to apply it to the scars twice a day.

For the first time in years, I felt free of the humiliation of being different, and I felt light because I had left my ugliness behind.

But this imprisonment and the label “ex-con” would follow me for life.

I had no idea how people would treat me, or if they would embrace me, living with my flaws exposed. I’d never given anyone the chance.

I didn’t tell Ella that her physical defects were disappearing for me, but I did tell her about how much time and energy I had put into maintaining my image, how much money I had spent making an

impression, how many people I had hurt, and how much stress had come with creating an illusion.

“I wanted everyone to think I was perfect,” I said, as if I’d had some great insight.

“Well,” Ella said, “you ain’t gotta worry about that no more.”

She was right. My conviction had been splashed across the front pages of newspapers. It had been the top story of the evening news. The scandal rocked my hometown. The behaviors I had developed to hide business setbacks, cash shortfalls, and any hint of failure were exposed on April 9, 1992. A Thursday.

The

Coast Magazine

offices were unusually quiet. And empty. All twenty-nine employees were attending an advertising sales symposium. Helen Berman, a sales expert from Washington state, had flown in to lead a motivational seminar for my staff.

I received a phone call from Albert Dane, my loan officer at Hancock Bank. Albert had helped our company grow from the very beginning. He had arranged for equipment leases, short-term loans, and credit card processing. He was a friend and supporter of our business.

“You need to come down to the bank,” Albert said. I looked at the clock. The bank had just opened for the morning. I asked if there were some problem. “You just need to come down here,” he repeated.

I packed my briefcase and checked the notes I’d made the day before at the bottom of my planner—a $419,000 check written on the Hancock Bank account; $345,000 drawn on Peoples Bank. I hoped some glitch had come to the bank’s attention that could easily be resolved. But I knew better. Albert wouldn’t call if the news weren’t awful.

I looked out of my window at the panorama of the coast. I stood for a moment. The beach and gulf were bright and clear in the morning light.

On my walk to Hancock Bank, I passed the offices where my father and his grandfather had practiced law. Two blocks down was where I had visited my grandfather in the purchasing office of Mis

sissippi Power. Five generations of my family had lived and worked in Gulfport as attorneys, teachers, surveyors, and entrepreneurs. This was my town, and I had hoped to be its greatest champion. My magazine depicted the region without its blemishes or flaws, like a magic mirror that reflected away any imperfections.

I walked slowly. I wanted to remember how Gulfport felt, and how the town felt about me. I had made many friends. I had made them look good in my magazines. Of course, it had ultimately been about making me look good. If Albert had discovered the kiting, I wondered if I would have time to get investors to cover the loss, like I did in Oxford.

I stepped onto an escalator that led to the second-floor mezzanine, the main bank floor. As the mechanical stairs lifted me upward I saw Albert waiting for me at the top. He directed me to the conference room where I’d been many times before for meetings about loans, equipment leases, and acquisitions.

I sat at one end of the large oval conference table. Albert sat at the other, as if he wanted to be as far away from me as possible. A woman I had never seen sat to his left. He looked down at the table as he told me that the FDIC had been at the bank doing an audit. He stammered about some procedures the bank went through before the auditors arrived. Then he looked up. “It’s come to our attention that you’ve been kiting checks.”

I felt the blood rush into my face. I felt hot all over. But I acted as if I didn’t know what that meant.

“Best we can determine,” he said, “the checks total somewhere around a million dollars.”

I wanted to correct him, but I thought it better to be perceived as stupid than criminal. I looked down at the table. I was ashamed.

Albert read me the bank’s policy. They would not accept any deposits that were not in cash. They would notify the FBI. They would notify the other banks on the coast. They would not entertain any loans. They would begin foreclosure on any liens on my assets. Then, he added that my uncle Knox, the bank’s primary attorney, had been made aware of my actions.

As we left the conference room, I told Albert I was sure I could cover the overdraft.

Looking at the floor and turning away from me, he said, “I hope you’re right.”

As I rode the escalator down to street level, I considered what I could do. And for the first time in years, I didn’t know. I was certain of only one thing. That nothing, ever again, would be the same.