Independence (41 page)

Authors: John Ferling

But Fox’s standing as a political figure soon overshadowed the tattle about his personal habits. As a student, Fox had been thought the most gifted speaker in his class, and during his first five years in the Commons he spoke 254 times. Only eight of his colleagues spoke more frequently. His speeches were seldom prepared in advance, and many were delivered following a night with little or no sleep. But this precocious young man took on the giants of his time and held his own, a talent that astounded veteran politicians. While Fox was an adroit speechmaker, he was nearly unequaled in the give and take of a debate. A contemporary exclaimed that many spectators who watched as he debated “all off-hand” found his performances “a most extraordinary thing.” One of his biographers wrote that Fox “in unprepared arguments … transcended any speaker in the history of Parliament.” Edmund Burke concurred, noting that Fox “rose by slow degrees to be the most brilliant and accomplished debater that the world ever saw.”

6

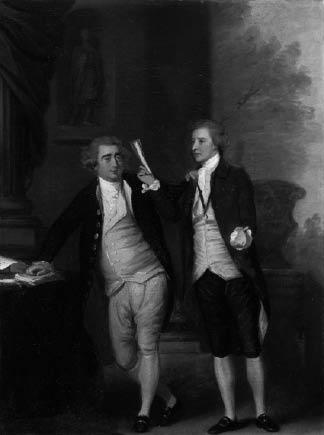

Edmund Burke and Charles James Fox by Thomas Hickey. Members of the House of Commons, Burke and Fox were the foremost critics of the government’s policy of coercion and force. They insisted that ministerial policy would drive the colonists to declare independence. (National Gallery of Ireland)

Fox launched his career as a Tory. He served North well in his initial years and was rewarded with seats on the Admiralty and Treasury boards. Some thought he might have been brought into the ministry had it not been for his youth. (Fox did not reach his majority until four days after North became the prime minister.) But in 1772 Fox broke with the government over a series of domestic issues and resigned from the Admiralty Board. “Charles Fox is turned patriot and is already attempting to pronounce the words ‘country,’ ‘liberty,’ ‘corruption,’ with what success time will discover,” Edward Gibbon noted happily as his young colleague commenced his transition to Whiggism. If the Whigs were delighted by Fox’s apostasy, George III was outraged. The king told the prime minister that “the Young Man has so thoroughly cast off every principle of common honor and honesty that he must become as contemptible as he is odious.” Ever obliging to his monarch, North saw to Fox’s removal from his remaining government post. In dismissing Fox from the Treasury Board, North informed him of the decision in a scornful note: “his Majesty has thought proper to order a new commission of the Treasury to be made out, in which I do not perceive your name.” Fox at first thought he was the victim of a practical joker. When he learned the truth, he was furious, and he concluded that it was unlikely that he would ever be asked to be part of a ministry so long as George III sat on the throne. Furthermore, Fox was estranged from both North’s government and the opposition.

7

It was in the midst of this predicament that Fox discovered the American problem. Until 1775 he had been silent when the American debates stirred the Commons. He had not taken a stand during the heated battles over the Coercive Acts. He had merely responded to a fellow MP who had framed the issue as a “dilemma of conquering or abandoning America” with the remark, “if we are reduced to that, I am for abandoning America.” Fox remained in the background during the debate on the supposedly conciliatory terms that North offered the colonists in February 1775, only prophesying that “the Americans will reject them with disdain.” Though his criticism of the North Peace Plan was muted, the prime minister publicly responded that Fox was backing the American rebels because of his resentment at having been ousted from the Treasury Board. Fox denied the charge—had his conduct been driven by rancor, he said, he would long ago have revealed instances of North’s “unexampled treachery and falsehood”—but on the floor of the Commons, he pledged to join henceforth with Burke to compel the prime minister “to answer [for] the mischiefs occasioned by his negligence, his inconsistency, and his incapacity.” He also shared with all who would listen his newfound conviction that having followed Lord North was “the greatest folly of his life.”

8

Fox made good on his pledge to ally with Burke. As a boy, he had known the Irishman, who was twenty years his senior; and when the two became colleagues in the House of Commons, they drew close, forming a warm friendship that seemed to grow from their mutual appreciation of literature and art, not to mention their deep respect for each other as penetrating thinkers and effective politicians. Burke looked on the gifted young man as a pupil and protégé, and he described Fox as “one of the pleasantest men in the world, as well as the greatest Genius that perhaps this country has ever produced.”

Burke’s critique of North’s policies in 1774 helped shape Fox’s thinking about American issues. But whereas Burke took up the cause of America because he understood that North’s policies would result in the loss of the colonies and the diminution of British power and prestige, Fox was drawn to the colonists’ plight in some measure because of the political opportunities that such a stance might yield.

9

In the fall of 1775, in the wake of the king’s address, Burke and Fox began to work hand in hand against what they saw as the mad and misguided direction that their country was being taken. They drew on each other’s talents. Burke was a spectacular orator. Fox was equally dazzling as a debater. Burke was informed and reasonable. Fox was eloquent, passionate, and biting, and as if wielding “the wand of the magician”—according to one observer—he was able to hold an audience in the palm of his hand.

10

From October 1775 through July 1776, and beyond, Burke and Fox emerged as the strongest voices for the much-outnumbered factions fighting in Parliament against the government’s policies toward America.

Fox’s speech in the debate on the king’s address was his first on the American war. He said little that had not been said on numerous occasions by others. He characterized North as “the blundering pilot” who had conveyed the nation to this crisis. He agreed that “the Americans had gone too far,” but he took issue with the monarch’s contention that the colonists sought independence. And like Grafton, Fox said that he had been deceived by the ministry. He had voted to send more troops to America in 1774 because North’s government had said that doing so would “ensure peace” without bloodshed. The ministers had been wrong. Fox pronounced that he could no longer “consent to the bloody consequences of so silly a contest about so silly an object, conducted in the silliest manner that history … had ever furnished … and from which we were likely to derive nothing, but poverty, misery, disgrace, defeat, and ruin.”

11

North largely left the government’s defense to Sandwich, who despite the bloodbaths suffered along Battle Road and on Bunker Hill, ludicrously raised the familiar canard about American “cowardice and want of spirit.”

12

The implication of his remarks was that victory would be easily attained. To no one’s surprise, when the debate concluded, both houses brushed back the opposition to the king’s position. By huge margins each house announced its “entire concurrence” with the monarch’s wish to “suppress this rebellion” with “the most decisive exertions.”

13

Ending the debate did not close the matter. Too many MPs wanted to discuss waging war. Some questioned the ministry’s authority to hire the foreign troops that were sent to the Mediterranean, and others raised doubts about the government’s estimates of the cost of expanding the naval and land forces in North America. In addition, the discussion kept coming back to the Olive Branch Petition. Congress’s entreaty to the king was read in the House of Lords early in the month, and on November 10 Richard Penn, who had carried the supplication across the Atlantic and was still in London, was summoned to testify. Among other things, he told the legislators that the sentiments of Congress reflected public opinion in the colonies and stressed that the Americans had gone to war “in defence of their liberties,” not to secure independence.

14

Many opposition MPs seized on Congress’s petition to assert that “the colonists were disposed to an amicable adjustment of differences.” Peace was possible, several observed. Others questioned the wisdom of pursuing a conquest that would be difficult, perhaps impossible, to achieve. One said that time would tell whether or not the colonists were cowardly, but there could be no question that they possessed arms and knew how to use them. More than one observed that the Americans also knew their country intimately and would use its rivers and other “natural barriers” to their advantage. Shelburne, who had been the first to ask why the king refused to receive Congress’s solicitation, spoke at length for a second time on the opportunity presented by the Olive Branch Petition for peacefully resolving the American question. Shelburne raised another matter that was on the minds of many. If the war lasted beyond 1776, he warned, the danger would grow that France would enter the fray. French belligerency, he said, would increase the likelihood that Congress would declare American independence and that America would win the war and make good on its break from the empire. Sandwich responded for the government. To concede to the demands of the rebels, he said, would “render up the rights of this country into the hands of the colonists.” To back down, he continued, would bring “disgrace” and lessen Great Britain’s standing “in the eyes of all Europe,” perhaps with fatal consequences.

15

A few days later, on November 16, Burke delivered the last of his three major speeches on the American crisis before independence. In the spring of 1774, and again during the following winter, he had made long, impassioned addresses attacking Britain’s taxation of the colonists, his second effort coming when war hung in the balance. Burke’s final oration was also incredibly lengthy—it consumed nearly four hours—and while his critics thought it “tedious” and not his best effort, many believed it was superior to Chatham’s antiwar speech during the previous winter.

16

Burke maintained that three approaches existed to the American problem. First, Great Britain could seek to crush the rebellion solely by the use of force. He doubted that victory could be achieved and was certain that it could not be accomplished by the number of troops that North had proposed sending to North America. Second, Great Britain could mix war and negotiation. Once the Continental army had suffered a sharp blow at the hands of the redcoats, terms could be offered to the colonial assemblies. Burke thought such a plan was fanciful. Rather than humbling the colonists, Britain’s use of force would render the Americans less willing to reunite with the mother country. The third, and surest, way to “restore immediate peace,” according to Burke, was to offer genuine peace terms without delay. The terms must not—could not—include the repeal of the Declaratory Act or of all American legislation enacted since 1763. To rescind the Declaratory Act would strip Parliament of all authority over America. To invalidate all recent acts might destroy Anglo-American commercial ties. Instead, Burke proposed offering the Continental Congress terms that included the renunciation of Parliament’s authority to tax the colonists; recognition of the Continental Congress’s authority to legislate for the colonies; repeal of the Townshend Duties and Coercive Acts; revocation of decades-old legislation that prohibited certain forms of manufacturing in the provinces; and pardons for all who had borne arms against Great Britain in this war.

Burke closed with an assessment of political realities in the colonies. A majority in Congress, he said, wished to reconcile with the mother country, and he believed that the terms he proposed were consistent with the conditions stipulated by the First Continental Congress. Shrewdly, Burke told the House of Commons that an offer of generous terms “would be the true means of dividing America” and crippling its solidarity behind the war, thus compelling Congress to accept peace.

17

Burke had hit upon the great fear of the likes of John Adams. Because Galloway had exposed what had occurred in the First Congress, and because of the correspondence of Adams and Harrison that had gone awry, London knew that deep divisions existed among the rebels. Burke held forth the option of exploiting those breaches as the best means of finding a peaceable solution to the crisis.

Fox had said in private that Burke’s speech “will be the fairest test in the world to try who is really for war and who is for peace.”

18

The first to answer Burke was Lord Germain, who during November’s American debate had finally succeeded Dartmouth as the American secretary. This was Germain’s maiden speech as a minister. It was midnight when he obtained the floor. Germain struck one observer as “much flustered,” and the new minister in fact confided to a friend that he “felt very awkward.”

19

He began by saying that he would never surrender the right of taxation. If that meant war, he did not shrink from it. Great Britain had great resources and was “equal to the contest.” The government, he went on, was sending the reinforcements asked for by the “officers serving on the spot.” They believed the increased numbers of regulars would be sufficient “to restore, maintain, and establish the power of this country in America,” and so did he. Germain pointed out that Congress had spurned the North Peace Plan. Indeed, it had not responded to the peace proposals made by Camden, Chatham, Burke, and Hartley during the previous winter. He declared that what Burke had proposed would not win over the Americans. The Americans, he argued, would see the terms proposed by Burke only “as gratuitous preliminaries” and would demand still more concessions, which “would put us on worse ground.”

20