Independence (45 page)

Authors: John Ferling

Four days after

Common Sense

hit the streets, a New Hampshire delegate reported that it had been “greedily bought up and read by all ranks of people” in Philadelphia. Another congressman related that it “has had a great Sale.” John Hancock said that the pamphlet “makes much talk here.” Franklin informed a correspondent that it “has made a great Impression here.” Samuel Adams, one of the first to purchase the tract, immediately sent copies to friends in Massachusetts, informing them that it had “fretted some folks here.” Other delegates eagerly wished to learn what the authorities back home thought of “the general spirit of it,” and some explicitly asked provincial leaders if they had been converted by

Common Sense

to “relish independency.”

44

Common Sense

hit like a bombshell. Some 250 pamphlets on the Anglo-American crisis had been published in America during the previous decade, and none had come close to equaling the sales of Paine’s tract. Dickinson’s

Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania

had outsold all rivals before 1776, but within a few months, nearly one hundred times more copies of

Common Sense

may have been sold than Dickinson’s immensely popular leaflet had realized during its eight-year life span. Timing was obviously crucial for Paine’s success, as was his crisp and lucid writing style. But so too was his palpable rage at Great Britain. Unbridled fury seemed to leap from the pages of the pamphlet. Paine’s wrath struck a responsive chord with Americans who were beside themselves with anger at a mother country that made war on its colonies and willfully destroyed port cities, incited Indian attacks, and fomented slave insurrections.

Paine’s euphoria at an American Revolution—a term that had not yet come into common usage—also transported readers. He provided a transcendent meaning for the events that were churning up the lives of the inhabitants of the colonies. Not only did the fate of contemporaries hang in the balance, Paine said; unborn generations of Americans and Europeans also depended on the creation of an independent America. “ ’Tis not the concern of a day, a year, or an age; posterity are virtually involved in the contest, and will be more or less affected even to the end of time, by the proceedings now,” Paine wrote. He proclaimed that “a new era” had begun on April 19, 1775—the day the war began—an epoch that would be ushered in by cleansing changes, none more important than the republicanism that would supplant rule by monarchy and privileged nobility, preserving “the RIGHTS OF MANKIND.” “The

time hath found us

,” he declared, and it had brought forth the “seed-time of continental union, faith, and honor,” and above all of American nationhood and American independence. No one had said such things in print previously, but across the broad landscape countless Americans took to heart what Paine had written, and their ready acceptance of his radical message quickened the pace toward American independence.

45

CHAPTER 9

“W

E

M

IGHT

G

ET

O

URSELVES UPON

D

ANGEROUS

G

ROUND

”

J

AMES

W

ILSON,

R

OBERT

M

ORRIS,

L

ORD

H

OWE, AND THE

S

EARCH FOR

P

EACE

ONE “EVENT HAS BROT ANOTHER ON,”

Samuel Adams remarked early in 1776.

1

He understood that the war was driving nearly every step that Congress took. The dynamic of hostilities was reshaping attitudes and shredding the already tattered remnants of the colonists’ devotion to the mother country. The hard and bitter feelings that had swept over Great Britain in the wake of Lexington and Concord were now matched in an America that had learned of Falmouth and Lord Dunmore’s proclamation. But nothing to this point in the war had shaken the reconciliationists as badly as the simultaneous blows of the king’s fierce and unbending stance and Thomas Paine’s assault on the very idea of maintaining ties with the mother country.

With the tide running against those who favored reconciliation, and with their options increasingly limited, Dickinson and his followers launched a final initiative at the outset of 1776. In August, and again in October, the king had justified the use of force on the premise that Congress was committed to American independence. On January 9, the day after the text of the monarch’s address to Parliament reached Philadelphia, James Wilson, a Pennsylvania delegate who looked on Dickinson as his mentor, moved that Congress “declare to their Constituents and the World their present Intentions respecting an Independency.” A New Jersey congressman noted in his diary that Wilson was “strongly supported,” and it is a safe bet that at a minimum all four delegations from the mid-Atlantic colonies backed his motion.

2

Wilson and his adherents had two objectives. They wished to show America’s friends in England that the king was wrong to insist that the American rebels secretly planned to declare independence when the time was right. In addition, by disavowing independence, Wilson hoped to lay the groundwork for talks with the envoys that George III in October had so tantalizingly suggested were to be sent to America. On the day after Wilson spoke,

Common Sense

appeared. That provided the reconciliationists with an additional—and especially urgent—reason for acting. They prayed that a congressional repudiation of independence would derail whatever groundswell might be aroused by Paine’s persuasiveness.

The thirty-four-year-old Wilson, who served as the point man for this latest sally to halt America’s drift out of the empire, had grown up in a farming family in Caskardy in the Scottish Lowlands. Provided with a formal education that was to prepare him for the clergy, Wilson instead fell under the influence of the Enlightenment during his years at the University of St. Andrews. He endured one listless year of theological study following graduation, after which he dropped out of school and worked briefly as a tutor and bookkeeper. Unhappy and adrift, he sailed for America in 1765, hoping, like numerous other immigrants, to find some purpose to his life. Wilson landed in New York, though he quickly moved to Philadelphia, the larger of the two cities. Not long after his arrival, the

Letters from a Farmer

appeared and Dickinson bolted to fame. Ambitious and drawn to politics himself, Wilson in 1767, at age twenty-five, applied to study law with Dickinson. Completing his apprenticeship in less than a year, Wilson moved to Reading, a town of a few hundred inhabitants northwest of Philadelphia, and opened a legal practice. With little competition, he rapidly succeeded. Filled with confidence, Wilson after two years moved to Carlisle, a larger frontier town teeming with immigrants, including many from Scotland. He prospered there as well. Within two years he had the largest caseload of any attorney in town, and in 1771, merely six years after crossing the Atlantic, he married a wealthy heiress, the stepdaughter of an influential ironmaster.

Like John Adams, Wilson largely remained aloof from politics until the Tea Act and Intolerable Acts crises, when he served on local committees that opposed parliamentary taxation. Later, he was part of the movement that pressured Galloway to have the assembly sanction the Continental Congress. Also like Adams, Wilson published a pamphlet in 1774 that attacked Parliament’s claims of unlimited power over the colonies. In most respects, Wilson shared Dickinson’s outlook, especially with regard to American independence. The one significant difference in their outlook was that, by the eve of the war, Wilson denied that Parliament could exercise any authority over the colonies.

Dickinson and his former student remained close. When Galloway resigned from the Pennsylvania delegation to the Second Continental Congress, Dickinson had a hand in securing Wilson’s appointment to the vacant seat in May 1775. Wilson remained a backbencher throughout his first year in Congress, in part perhaps because his somewhat standoffish manner and forbiddingly cold exterior prevented close relationships with delegates from other colonies. In addition, like Adams at the First Congress in 1774, Wilson, somewhat unsure of himself, likely was overawed for a time by his more experienced colleagues. Yet while Wilson seldom entered debates, he served on numerous committees, where he established a reputation as a bright, thoughtful, and dependable colleague. In the summer of 1775 John Adams pronounced that Wilson’s “Fortitude, Rectitude, and Abilities too, greatly outshine” those of Dickinson.

3

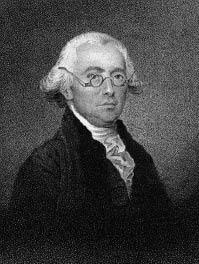

James Wilson. A staunch reconciliationist and follower of John Dickinson, Wilson opposed independence until the last minute, when he voted to break with Great Britain. He had a long career as an American public official following independence. (Private Collection/ The Bridgeman Art Library)

When Wilson took the floor in January 1776, he may have felt that the time had arrived for him to play a more prominent role. He may also have been driven by desperation, given the increasing plight of the reconciliationists. The possibility exists, too, that those who shared his outlook selected him to take the lead in this fight not only because he was a fresh face but also because his outlook on Parliament’s supremacy was slightly more progressive than Dickinson’s. Or, Wilson may have acted when he did because of the role he was playing at the time in a largely forgotten episode—negotiations with a self-appointed emissary of Lord North.

Through contacts with talkative New York and New Jersey delegates who had attended the First Congress, Thomas Lundin, Lord Drummond, had learned in December 1774 of the narrow defeat of Galloway’s compromise proposal. Drummond, a Scotsman who had crossed to America and settled in New Jersey three years after Wilson’s emigration, also appears to have gleaned that the initial Congress had been deeply divided and that many moderate congressmen distrusted their more radical colleagues from New England. Armed with this inside information, Drummond hurried to London shortly after the First Continental Congress adjourned. During the winter of 1775, hard on the heels of Dartmouth’s failure to lure Franklin into meaningful negotiations, Drummond was given an audience with Lord North and the American secretary. The Scotsman presented a peace proposal that he had drafted, a plan that bore a striking similarity to the so-called North Peace Plan recently presented to Parliament. Both North and Dartmouth thought Drummond might be useful, but the prime minister made no decision about using him as an emissary for another six months.

In the wake of Lexington-Concord and Bunker Hill, with the ministry scrambling to find additional troops to send to America, and with North at least privately despairing of ever suppressing the American rebellion by force, the prime minister decided to put Drummond to use as an unofficial envoy. North asked him to return to Philadelphia. Drummond was to use his contacts to determine what Congress would accept, and what London would have to relinquish, to settle Anglo-American differences. No doubt, too, Lord North was searching for a means of sowing fatal divisions among the congressmen. It seems clear that Drummond was instructed not to drag his feet. North wanted to know whether any chance existed for fruitful negotiations before substantive military operations began in the spring or summer of 1776. The thirty-three-year-old Scottish nobleman sailed from London in September and reached Philadelphia late in December, arriving in the city around the same time as Bonvouloir, Penet, and Pliarne. Within days, possibly hours, Drummond had quietly opened discussions with delegates from at least four colonies: New York, New Jersey, South Carolina, and Pennsylvania. One of the delegates with whom he met was James Wilson.