India After Gandhi (54 page)

Read India After Gandhi Online

Authors: Ramachandra Guha

Tags: #History, #Asia, #General, #General Fiction

There was some propaganda activity by Tibetan refugees in Kalimpong,

the import of which was, however, greatly exaggerated by the Chinese. In fact, much louder protests had emanated from Indian sources, in particular the politician turned social worker Jayaprakash Narayan. ‘JP’ was a fervent advocate for Tibetan independence, a cause also supported by other, less disinterested elements in Indian politics, such as the Jana Sangh, which wanted New Delhi openly to ally with the United States in the Cold War and seek its assistance in ‘liberating’ Tibet.

7

But, as the foreign secretary assured the Chinese ambassador a month after the Dalai Lama’s flight into exile, ‘India has had and has no desire to interfere in internal happenings in Tibet’. The exiled leader ‘will be accorded respectful treatment in India, but he is not expected to carry out any political activities from this country’. This was the government’s position, from which some Indians would naturally dissent. For, as the foreign secretary pointed out, ‘there is by law and Constitution complete freedom of expression of opinion in Parliament and the press and elsewhere in India. Opinions are often expressed in severe criticism of the Government of India’s policies.’

This was not a nuance Peking could easily understand. For, at least in public, there could not be any criticism of the government’s policies within China. The difference between these two political systems – call them ‘totalitarianism’ and ‘democracy’ – was most strikingly reflected in an exchange about an incident that took place in Bombay on 20 April. According to the Chinese version – communicated to New Delhi by Peking in a letter dated 27 April – a group of protesters raised slogans and made speeches which

branded China’s putting down of the rebellion in her own territory, the Tibetan Region, as [an] imperialist action and made all sorts of slanders. What is more serious is that they pasted up a portrait of Mao Tse-tung, Chairman of the People’s Republic of China, on the wall of the Chinese Consulate-General and carried out wanton insult by throwing tomatoes and rotten eggs at it. While these ruffians were insulting the portrait, the Indian policemen stood by without interfering with them, and pulled off the encircling spectators for the correspondents to take photographs . . .

This incident in Bombay constituted, in Peking’s view, ‘a huge insult to the head of state of the People’s Republic of China and the respected and beloved leader of the Chinese people’. It was an insult which ‘the masses of the six hundred and fifty million Chinese people absolutely cannot

tolerate’. If the matter was ‘not reasonably settled’, said the complaint, in case ‘the reply from the Indian Government is not satisfactory’, the ‘Chinese side will never come to a stop without a satisfactory settlement of the matter, that is to say, never stop even for one hundred years’.

In reply, the Indian government ‘deeply regret[ted] that discourtesy was shown to a picture of Chairman Mao Tse-tung, the respected head of a state with which India has ties of friendship’. But they denied that the policemen on duty had in anyway aided the protesters; to the contrary, they ‘stood in front of the [Mao] picture to save it from further desecration’. The behaviour of the protesters was ‘deplorable’, admitted New Delhi, but

IIIthe Chinese Government are no doubt aware that under the law in India processions cannot be banned so long as they are peaceful . . . Not unoften they are held even near the Parliament House and the processionists indulge in all manner of slogans against high personages in India. Incidents have occurred in the past when portraits of Mahatma Gandhi and the Prime Minister were taken out by irresponsible persons and treated in an insulting manner. Under the law and Constitution of India a great deal of latitude is allowed to the people so long as they do not indulge in actual violence.

In the first week of September 1959 the government of India released a White Paper containing five years of correspondence with its Chinese counterpart. The exchanges ranged from those concerning trifling disputes, occasioned by the straying by armed patrols into territory claimed by the other side, to larger questions about the status of the border in the west and the east and disagreements about the meaning of the rebellion in Tibet.

For some time now opposition MPs, led by the effervescent young Jana Sangh leader Atal Behari Vajpayee, had been demanding that the government place before Parliament its correspondence with the Chinese. The release of the White Paper was hastened by a series of border incidents in August. Chinese and Indian patrols had clashed at several places in NEFA. One Indian post, at Longju, came under sharp fire from the Chinese and was ultimately overwhelmed.

Unfortunately for the government, the appearance of the White Paper coincided with a bitter spat between the defence minister and his chief of army staff. The minister was Nehru’s old friend V. K. Krishna Menon, placed in that post in 1957 as compensation for drawing him away from diplomatic duties. The appointment was at first welcomed within the army. Previous incumbents had been lacklustre; this one was anything but, and was close to the prime minister besides. But just as he seemed well settled in his new job, Menon got into a fight with his chief of staff, General K. S. Thimayya, a man just as forceful as he was.

The son of a coffee planter in Coorg, standing 6’ 3” in his socks, Thimayya had an impressive personality and amore impressive military record. When a young officer in Allahabad, he had met an elderly gentleman in a cinema who asked him, ‘How does it feel to be an Indian wearing a British army uniform?’ ‘Timmy’ answered with one word: ‘Hot’ . The old man was Motilal Nehru, father of Jawaharlal and a celebrated nationalist himself. Later, when they had become friends, Thimayya asked him whether he should resign his commission and join the nationalist movement. Motilal advised him to stay in uniform, saying that after freedom came India would need officers like him.

8

Thimayya fought with distinction in the Second World War before serving with honour in the first troubled year of Indian freedom. He oversaw the movement of Partition refugees in the Punjab and was then sent to Kashmir, where his troops successfully cleared the Valley of raiders. Later, he headed a United Nations truce team in Korea, where he supervised the disposition of 22,000 communist prisoners of war. His leadership was widely praised on both sides of the ideological divide, by the Chinese as well as the Americans.

‘Timmy’ was the closest the pacifist Indians had ever come to having an authentic modern military hero.

9

However, he did not see eye to eye with his defence minister. Thimayya thought that his troops should be better prepared for a possible engagement with China, but Krishna Menon insisted that the real threat came from Pakistan, along whose borders the bulk of India’s troops were thus deployed. Thimayya was also concerned about the antiquity of the arms his men currently carried. These included the .303 Enfield rifle, which had first been used in the First World War. When the general suggested to the minister that India should manufacture the Belgian FN4 automatic rifle under licence, ‘Krishna Menon said angrily that he was not going to have NATO arms in the country’.

10

In the last week of August 1959 Thimayya and Menon fell out over the latter’s decision to appoint to the rank of lieutenant general an officer named B. M. Kaul, in supersession of twelve officers senior to him. Kaul had a flair for publicity – he liked to act in plays, for example. He had supervised the construction of a new housing colony, which impressed Menon as an example of how men in uniform could contribute to the public good. In addition, Kaul was known to Jawaharlal Nehru, a fact he liked to advertise as often as he could.

11

Kaul was not without his virtues. A close colleague described him as ‘a live-wire – quick-thinking, forceful, and venturesome’. However, he ‘could also be subjective, capricious and emotional’.

12

Thimayya was concerned that Kaul had little combat experience, for he had spent much of his career in the Army Service Corps, an experience which did not really qualify him for a key post at Army Headquarters. Kaul’s promotion, when added to the other insults from his minister, provoked General Thimayya into an offer of resignation. On 31 August 1959 he wrote to the prime minister conveying how ‘impossible it was for me and the other two Chiefs of Staff to carry out our responsibilities under the present Defence Minister’. He said the circumstances did not permit him to continue in hispost.

13

The news of the army chief’s resignation leaked into the public domain. The matter was discussed in Parliament, and in the press as well. Opposing Thimayya were communists such as E. M. S. Namboodiripad, who expressed the view that the general should be court-martialled, and crypto-communist organs such as the Bombay weekly Blitz, which claimed that Thimayya had unwittingly become a tool in the hands of the ‘American lobby’. Those who sided with him in his battle with the defence minister were

Blitz’

s great (and undeniably pro-American) rival, the weekly

Current,

as well as large sections of the non-ideological press. The normally pro-government

Hindustan Times

said that ‘Krishna Menon must go’, not Thimayya. It accused the minister of reducing the armed forces to a ‘state of near-demoralization’ by trying to create, at the highest level, a cell of officers who would be personally loyal to him.

14

Some hoped that the outcry over Thimayya’s resignation would force Krishna Menon to also hand in his papers. Writing to the general, a leading lawyer called the minister an ‘evil genius in Indian politics’, adding, ‘If as a result of your action, Menon is compelled to retire, India will heave asigh of relief, and you will be earning the whole-hearted

gratitude of the nation.’ Then Nehru called Thimayya into his office and over two long sessions persuaded him to withdraw his resignation. He assured him that he would be consulted in all important decisions regarding promotions. An old colleague of Timmy’s, a major general now retired to the hill town of Dehradun, wrote to his friend saying he should have stuck to his guns. For ‘the solution found is useless as now no one has been sacked or got rid of. The honeymoon cannot last long as you will soon find out.’

15

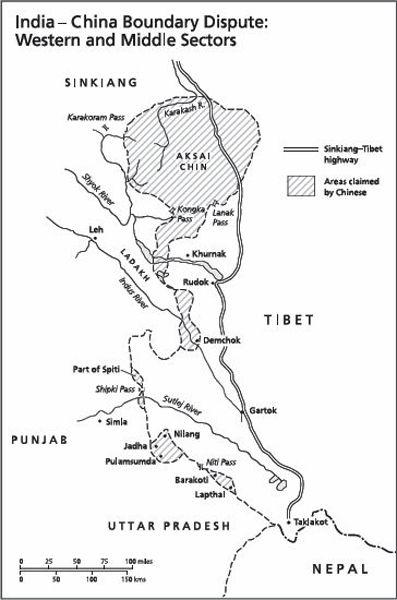

The release of the White Paper on China, against the backdrop of the general’s resignation drama, intensified the feelings against the defence minister. For even members of Parliament had not known of the extent of China’s claim on Indian territory. That the Chinese had established posts and built a paved road through what, at least on their maps, was India was seen as an unconscionable lapse on the part of those charged with guarding the borders. Opposition politicians naturally went to town about China’s ‘cartographic war against India’. As a socialist MP put it, New Delhi might still believe in ‘Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai’, but Peking followed Lenin’s dictum that ‘promises, like piecrusts, are meant to be broken’.

16

Perhaps the prime minister should have been held accountable, but for the moment the fingers were pointed at his pet, Krishna Menon. If the country was ‘woefully unprepared to meet Chinese aggression’, said the

Current

, the fault must lie with the person ‘at the helm of India’s Defence Forces’, namely, the defence minister. Even Congress Party members were now calling for Menon’s head. The home minister, Govind Ballabh Pant, an old veteran of the freedom struggle and a longtime comrade of Nehru’s, advised the prime minister to change Menon’s portfolio – to keep him in the Cabinet, but allot him something other than Defence.

17

The respected journalist B. Shiva Rao, now an MP, wrote to Nehru that he was ‘greatly disturbed by your insistence on keeping Krishna Menon in the Cabinet. We are facing a grave danger from a Communist Power. As you are aware, there are widespread apprehensions about his having pro-Communist sympathies’. It was ‘not easy for me to write this letter’, said Shiva Rao, and ‘I know it will be a very difficult decision for you to make’. However, ‘this is an emergency whose end no one can predict’.

18

Nehru, however, stuck to his guns – and to Krishna Menon. Meanwhile the ‘diplomatic’ exchanges with China continued. On 8 September 1959 Chou En-lai finally replied to Nehru’s letter of 22 March that had set out the Indian position. Chou expressed surprise that India wished the Chinese to ‘give formal recognition to the situation created by the application of the British policy of aggression against China’s Tibet region’. The ‘Chinese Government absolutely does not recognise the so-called McMahon Line’. It insisted that ‘the entire Sino-Indian boundary has not been delimited’, and called for a fresh settlement, ‘fair and reasonable to both sides’. The letter ended with a reference to the increasing tension caused by the Tibet rebellion, after which Indian troops started ‘shielding armed Tibetan bandits’ and began ‘pressing forward steadily across the eastern section of the Sino-Indian boundary’.