India After Gandhi (55 page)

Read India After Gandhi Online

Authors: Ramachandra Guha

Tags: #History, #Asia, #General, #General Fiction

Nehru replied almost at once, saying that the Indians ‘deeply resent this allegation’ that ‘the independent Government of India are seeking to reap a benefit’ from British imperialism. He pointed out that between 1914 and 1947 no Chinese government had objected to the McMahon Line. He rejected the charge that India was shielding armed Tibetans. And he expressed ‘great shock’ at the tone of Chou’s letter, reminding him that India was one of the first countries to recognize the People’s Republic and had consistently sought to be friend it.

19

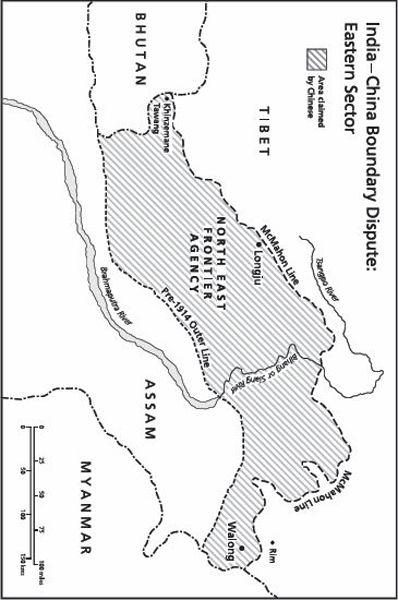

By this time, the India–China exchange comprised bullets as well as letters. In late August 1959 there was a clash of arms at Longju, along the McMahon Line in the eastern sector. Then in late October1959 an Indian patrol in the Kongka Pass area of Ladakh was attacked by a Chinese detachment. Nine Indian soldiers were killed, and as many captured. The Chinese maintained that the Indians had come deliberately into their territory; the Indians answered that they were merely patrolling what was their own side of the border.

These clashes prompted New Delhi to review its frontier policy. Remarkably, till this time responsibility for the border with China had rested not with the army but with the Intelligence Bureau. Such border posts as existed were manned by paramilitary detachments, the Assam Rifles in the east and the Central Reserve Police in the west. Regular military forces were massed along the border with Pakistan, which was considered India’s main and perhaps sole military threat. But after the Longju and Kongka Pass incidents, the 4th Division was pulled out of Punjab and sent to NEFA. This was a considerable change; trained for tank warfare in the plains, the 4th would now have to operate in a very different terrain altogether.

Through this new ‘forward policy’, the Indian government aimed to inhabit no-man’s-land by siting a series of small posts along or close to

the border. The operation was much touted in Delhi, where maps sprung up in Defence Ministry offices with little blue pins marking where these posts had been located. Not to be found on these maps were the simultaneous attempts by the Chinese to fill in the blanks, working from their side of what was now a deeply contested border.

20

By 1959, at least, it was clear that the Indian and Chinese positions were irreconcilable. The Indians insisted that the border was, for the most part, recognized and assured by treaty and tradition; the Chinese argued that it had never really been delimited. The claims of both governments rested in part on the legacy of imperialism; British imperialism (for India), and Chinese imperialism (over Tibet) for China. In this sense, both claimed sovereignty over territory acquired by less-than-legitimate means.

In retrospect, it appears that the Indians underestimated the force of Chinese resentment against ‘Western imperialism’. In the first half of the twentieth century, when their country was weak, it had been subject to all sorts of indignities by the European powers. The McMahon Line was one of them. Now that, under the communists, China was strong, it was determined to undo the injustices of the past. Visiting Peking in November 1959, the Indian lawyer Danial Latifi was told by his Chinese colleagues that ‘the McMahon Line had no juridical basis’. Public opinion in China appeared ‘to have worked itself up to a considerable pitch’ on the border issue. Reporting his conversations to Jawaharlal Nehru, Latifi tellingly observed, ‘As you know, probably too well, it is difficult

in any country

to make concessions once the public has been told it [the territory under dispute] forms part of the national homeland.’

21

It is also easy in retrospect to see that, after the failure of the Tibetan revolt, the government of India should have done one or both of the following: (i) strengthened its defences along the Chinese border, importing arms from the West if need be; (ii) worked seriously for afresh settlement of the border with China. But the non-alignment of Nehru precluded the former and the force of public opinion precluded the latter. In October 1959 the

Times of India

complained that the prime minister had shown ‘an over-scrupulous regard for Chinese susceptibilities and comparative indifference towards the anger and dismay with

which the Indian people have reacted’.

22

Another newspaper observed that Nehru was ‘standing alone against the rising tide of national resentment against China’.

23

As Steven Hoffman has suggested, the policy of releasing White Papers limited Nehru’s options. Had the border dispute remained private the prime minister could have used the quieter back-channels of diplomatic compromise. But with the matter out in the open, sparking much angry comment, he could only ‘adopt those policies that could conceivably meet with approval from an emotionally aroused parliament and press’. The White Paper policy precluded the spirit of give and take, and instead fanned patriotic sentiment. The Kongka Pass incident, in particular, had led to furious calls for revenge from India’s political class.

24

After the border clashes of September and October 1959, Chou En-lai wrote suggesting that both sides withdraw twenty kilometres behind the McMahon Line in the east, and behind the line of actual control in the west. Nehru, in reply, dismissed the suggestion as merely a way of legitimizing Chinese encroachments in the western sector, of keeping ‘your forcible possession intact’. The ‘cause of the recent troubles’, he insisted, ‘is action taken from your side of the border’. Chou now pointed out that, despite its belief that the McMahon Line was illegal, China had adhered to a policy of ‘absolutely not allowing its armed personnel to cross this line [while] waiting for a friendly settlement of the boundary question’. Thus,

the Chinese Government has not up to now made any demand in regard to the area south of the so-called McMahon line as a precondition or interim measure, and what I find difficult to understand is why the Indian Government should demand that the Chinese side withdraw one-sidedly from its western frontier area.

This was an intriguing suggestion which, stripped of its diplomatic code, read, ‘You keep your (possibly fraudulently acquired) territory in the East, while we shall keep our (possibly fraudulently acquired) territory in the West.’

25

Writing in the

Economic Weekly

in January 1960, the Sinologist Owen Lattimore astutely summed up the Indian dilemma. Since the boundary with China was self-evidently a legacy of British imperialism, the ‘cession of a large part of the disputed territory . .. would not involve Indian national pride had it not been for the way the Chinese have been trying to draw the frontier by force, without negotiation’. For ‘what Mr Nehru

might concede by reasonable negotiations between equals he would never concede by abject surrender’.

26

In the same issue of the journal a contributor calling himself ‘Pragmatist’ urged a strong programme of defence preparedness. The Peking leadership, he wrote acidly, ‘may not think any better of the armed forces of India than Stalin did of those of the Vatican’. The Chinese army was five times the strength of its Indian counterpart, and equipped with the latest Soviet arms. Indian strategic thinking, for so long preoccupied with Pakistan, must now consider seriously the Chinese threat, for the friendship between the two countries had ‘definitely come to an end’. Now, the ‘first priority in our defence planning’ must be ‘keeping Chinese armies on the northern side of the border’. India should train mountain warfare units, and equip them with light and mobile equipment. Waiting in support must be a force of helicopters and fighter-bombers. For ‘the important thing’ , said ‘Pragmatist’, is to ‘build up during the next two or four years, a strong enough force which will be able to resist successfully any blitzkrieg across our Himalayan borders’.

27

The political opposition, however, was not willing to wait that long. ‘The nation’s self-interests and honour’, thundered the president of the Jana Sangh in the last week of January 1960, ‘demand early and effective action to free the Indian soil from Chinese aggression’. The government in power had ‘kept the people and Parliament entirely ignorant in respect of the fact of aggression itself’, and now ‘it continues to look on helplessly even as the enemy goes on progressively consolidating its position in the occupied areas’.

28

Suspicion of the Chinese, however, was by no means restricted to parties on the right. In February 1960 President Rajendra Prasad commented on the ‘resentment and anger’ among the students of his native Bihar. These young people, he reported, wanted India to vacate ‘the Chinese aggression’ from ‘every inch of our territory’. They ‘will not tolerate any wrong or weak step by the government’.

29

With positions hardening, New Delhi invited Chou En-lai for a summit meeting on the border question. The meeting was scheduled for late April, but in the weeks leading up to it there were many attempts to queer the pitch. On 9 March the Dalai Lama appealed to the world ‘not to forget the fight of Tibet, a small but independent country occupied by force and by a fanatic and expansionist power’. Three days later a senior Jana Sangh leader urged the prime minister to ‘not

compromise the sentiments of hundreds of millions of his countrymen , and ‘to take all necessary steps against further encroachment by the Chinese . Less expected was a statement of the Himalayan Study Group of the Congress Parliamentary Party, which urged the prime minister to take a ‘firm stand on the border issue’.

30

In the first week of April the leaders of the non-communist opposition sent a note to the prime minister reminding him of the ‘popular feeling’ with regard to China. They asked for an assurance that in his talks with Chou En-lai ‘nothing will be done which may be construed as a surrender of any part of Indian territory’.

31

Hemmed in from all sides, the prime minister now sought support from the Gandhian sage Vinoba Bhave, then on a walking tour through the Punjab countryside. Nehru spent an hour closeted with Bhave in his village camp; although neither divulged the contents of their talks, these became pretty clear in later speeches by the sage. On 5 April Bhave addressed a meeting at Kurukshetra, the venue, back in mythical time, of the great war between the Pandavas and the Kauravas. On this blood-soaked battlefield he offered a prayer for the success of the Nehru-Chou talks. ‘Distrust belonged to the dying political age,’ said the Gandhian. ‘The new age was building itself around trust and goodwill.’ The conversations with the Chinese visitor, hoped Bhave, would be free of anger, bitterness and suspicion.

It was not a message that went down well or widely. Five days before Chou En-lai was due, the Jana Sangh held a large demonstration outside the prime minister’s residence. Protesters held up placards reminding Nehru not to forget the martyrs of Ladakh and not to surrender Indian territory. The next day, the non-communist opposition held a mammoth public meeting in Delhi, where the prime minister was warned that if he struck a deal with the Chinese his ‘only allies would be the Communists and crypto-Communists’. In this climate, the respected editor Frank Moraes thought the talks were doomed to failure. The gulf between the two countries was ‘unbridgeable’, he wrote, adding: ‘If Mr Chou insists on maintaining all the old postures, all that Mr Nehrucan tell him politely is to go back to Peking and think again.’

Nehru, however, insisted that the Chinese prime minister ‘would be accorded a courteous welcome befitting the best traditions of this country’. Chou was then on a visit to Burma; an Indian viscount went to pick him up and fly him to Delhi. When he came in 1956, he had been given a stirring public reception; this time – despite the Indian

prime minister’s hopes – he arrived ‘amidst unprecedented security arrangements’, travelling from the airport in a closed car. The Hindu Mahasabha organized a ‘black flag’ demonstration against Chou, but his visit was also opposed by the more mainstream parties. Two jokes doing the rounds expressed the mood in New Delhi. One held that ‘Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai’ had become ‘Hindi-Chini Bye Bye’; the other asked why Krishna Menon was not in the Indian delegation for the talks, and answered, ‘Because he is in Mr Chou En-lai’s party.’

32

Chou En-lai spent a week in New Delhi, meeting Nehru every day, with and without aides. A photograph reproduced in the

Indian Express

after the second day of the talks suggested that they were not going well. It showed Chou raising a toast to Sino-Indian friendship, by clinking his glass with Mrs Indira Gandhi’s. Mrs Gandhi was stylishly dressed, in asari, but was looking quizzically across to her father. On the other side of the table stood Nehru, capless, drinking deeply and glumly from a wine glass while avoiding Chou En-lai’s gaze. The only Indian showing any interest at all was the vice-president, S. Radhakrishnan, seen reaching across to clink his glass with Chou’s.