Influence: Science and Practice (25 page)

Read Influence: Science and Practice Online

Authors: Robert B. Cialdini

The powerful influence of filmed examples in changing the behavior of children can be used as therapy for various other problems. Some striking evidence is available in the research of psychologist Robert O’Connor (1972) on socially withdrawn preschool children. We have all seen children of this sort: terribly shy, standing alone at the fringes of the games and groupings of their peers. O’Connor worried that this early behavior was the beginning of what could become a long-term pattern of isolation, which in turn could create persistent difficulties in social comfort and adjustment throughout adulthood. In an attempt to reverse the pattern, O’Connor made a film containing 11 different scenes in a nursery-school setting. Each scene began by showing a different solitary child watching some social activity and then actively participating, to everyone’s enjoyment. O’Connor selected a group of the most severely withdrawn children from four preschools and showed them this film. The impact was impressive. After watching the film, the isolates immediately began to interact with their peers at a level equal to that of the normal children in the schools. Even more astonishing was what O’Connor found when he returned to the schools six weeks later to observe. While the withdrawn children who had not seen O’Connor’s film remained as isolated as ever, those who

had

viewed it were now leading their schools in amount of social activity. It seems that this 23-minute movie, viewed just once, was enough to reverse a potential pattern of lifelong maladaptive behavior. Such is the potency of the principle of social proof.

3

3

Other research besides O’Connor’s suggests that there are two sides to the filmed-social-proof coin, however. The dramatic effect of filmed depictions on what children find appropriate has been a source of great distress for those concerned with frequent depictions of violence and aggression on television (Eron & Huesmann, 1985). Although the consequences of media violence on the aggressive actions of viewers are far from simple, the result of a review of 28 different experiments on the topic is compelling. After watching others act aggressively (versus nonagressively) on film, children and adolescents became more aggressive in their own personal situations (Wood, Wong, & Chachere, 1991). More recently, as concern in the United States has risen regarding the levels of obesity due to poor nutrition, health officials have worried that advertising depictions of fast food consumption in the media might spur poor nutritional choices by virtue of a social proof effect: “If everybody in the ads is ordering the extra crispy chicken, I can do it, too.” A study of Asian, Hispanic, African American, and White children confirmed the need to worry. The more fast food promotions a family experienced, the more fast food they consumed. But, this wasn’t the case because the ads changed parents’ attitudes toward fast food. Instead, in keeping with the mechanism of social proof, it was because parents’ perceived fast food consumption as more normal in their communities (Grier et al., 2007).

After the Deluge

When it comes to illustrating the strength of social proof, there is one illustration that is far and away my favorite. Several features account for its appeal: It offers a superb example of the much underused method of participant observation, in which a scientist studies a process by becoming immersed in its natural occurrence; it provides information of interest to such diverse groups as historians, psychologists, and theologians; and, most important, it shows how social evidence can be used on us—not by others, but by ourselves—to assure us that what we prefer to be true will seem to be true.

Looking for Higher (and Higher) Meaning

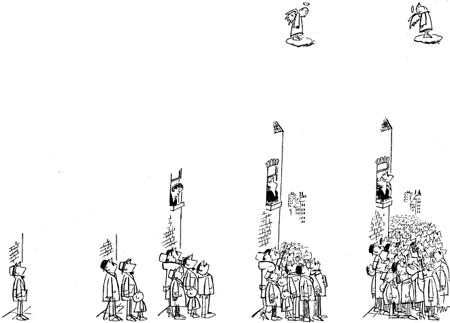

The draw of the crowd is devilishly strong.

© Punch/Rothco

The story is an old one, requiring an examination of ancient data, for the past is dotted with millennial religious movements. Various sects and cults have prophesied that on a particular date there would arrive a period of redemption and great happiness for those who believed in the group’s teachings. In each instance it has been predicted that the beginning of a time of salvation would be marked by an important and undeniable event, usually the cataclysmic end of the world. Of course, these predictions have invariably proved false, to the acute dismay of the members of such groups.

However, immediately following the obvious failure of the prophecy, history records an enigmatic pattern. Rather than disbanding in disillusion, the cultists often become strengthened in their convictions. Risking the ridicule of the populace, they take to the streets, publicly asserting their dogma and seeking converts with a fervor that is intensified, not diminished, by the clear disconfirmation of a central belief. So it was with the Montanists of second-century Turkey, with the Anabaptists of sixteenth-century Holland, with the Sabbataists of seventeenth-century Izmir, and with the Millerites of nineteenth-century America. And, thought a trio of interested social scientists, so it might be with a doomsday cult based in modern-day Chicago. The scientists—Leon Festinger, Henry Riecken, and Stanley Schachter—who were then colleagues at the University of Minnesota, heard about the Chicago group and felt it worthy of close study. Their decision to investigate by joining the group, incognito, as new believers and by placing additional paid observers among its ranks resulted in a remarkably rich firsthand account of the goings-on before and after the day of predicted catastrophe (Festinger, Riecken, & Schachter, 1964).

The cult of believers was small, never numbering more than 30 members. Its leaders were a middle-aged man and woman, whom for purposes of publication, the researchers renamed Dr. Thomas Armstrong and Mrs. Marian Keech. Dr. Armstrong, a physician on the staff of a college student-health service, had a long-held interest in mysticism, the occult, and flying saucers; as such, he served as a respected authority on these subjects for the group. Mrs. Keech, though, was the center of attention and activity. Earlier in the year she had begun to receive messages from spiritual beings, whom she called the Guardians, located on other planets. It was these messages, flowing through Marian Keech’s hand via the device of “automatic writing,” that formed the bulk of the cult’s religious belief system. The teachings of the Guardians were loosely linked to traditional Christian thought.

The transmissions from the Guardians, always the subject of much discussion and interpretation among the group, gained new significance when they began to foretell of a great impending disaster—a flood that would begin in the Western Hemisphere and eventually engulf the world. Although the cultists were understandably alarmed at first, further messages assured them that they and all those who believed in the lessons sent through Mrs. Keech would survive. Before the calamity, spacemen were to arrive and carry off the believers in flying saucers to a place of safety, presumably on another planet. Very little detail was provided about the rescue except that the believers were to make themselves ready for pickup by rehearsing certain passwords to be exchanged (“I left my hat at home.” “What is your question?” “I am my own porter.”) and by removing all metal from their clothes—because the wearing or carrying of metal made saucer travel “extremely dangerous.”

As Festinger, Riecken, and Schachter observed the preparations during the weeks prior to the flood date, they noted with special interest two significant aspects of the members’ behavior. First, the level of commitment to the cult’s belief system was very high. In anticipation of their departure from doomed Earth, irrevocable steps were taken by the group members. Most incurred the opposition of family and friends to their beliefs but persisted, nonetheless, in their convictions, often when it meant losing the affections of these others. In fact, several of the members were threatened by neighbors or family with legal actions designed to have them declared insane. Dr. Armstrong’s sister filed a motion to have his two younger children removed from his custody. Many believers quit their jobs or neglected their studies to devote full time to the movement. Some even gave or threw away their personal belongings, expecting them shortly to be of no use. These were people whose certainty that they had the truth allowed them to withstand enormous social, economic, and legal pressures and whose commitment to their dogma grew as they resisted each pressure.

The second significant aspect of the believers’ preflood actions was a curious form of inaction. For individuals so clearly convinced of the validity of their creed, they did surprisingly little to spread the word. Although they initially publicized the news of the coming disaster, they made no attempt to seek converts, to proselyte actively. They were willing to sound the alarm and to counsel those who voluntarily responded to it, but that was all.

The group’s distaste for recruitment efforts was evident in various ways besides the lack of personal persuasion attempts. Secrecy was maintained in many matters—extra copies of the lessons were burned, passwords and secret signs were instituted, the contents of certain private tape recordings were not to be discussed with outsiders (so secret were the tapes that even longtime believers were prohibited from taking notes of them). Publicity was avoided. As the day of disaster approached, increasing numbers of newspaper, television, and radio reporters converged on the group’s headquarters in the Keech house. For the most part, these people were turned away or ignored. The most frequent answer to their questions was, “No comment.” Although discouraged for a time, the media representatives returned with a vengeance when Dr. Armstrong’s religious activities caused him to be fired from his post on the college health service staff; one especially persistent newsman had to be threatened with a lawsuit. A similar siege was repelled on the eve of the flood when a swarm of reporters pushed and pestered the believers for information. Afterward, the researchers summarized the group’s preflood stance on public exposure and recruitment in respectful tones: “Exposed to a tremendous burst of publicity, they had made every attempt to dodge fame; given dozens of opportunities to proselyte, they had remained evasive and secretive and behaved with an almost superior indifference” (Festinger et al., 1964).

Eventually, when all the reporters and would-be converts had been cleared from the house, the believers began making their final preparations for the arrival of the spaceship scheduled for midnight that night. The scene as viewed by Festinger, Riecken, and Schachter must have seemed like absurdist theater. Otherwise ordinary people—housewives, college students, a high-school boy, a publisher, a physician, a hardware-store clerk and his mother—were participating earnestly in tragic comedy. They took direction from a pair of members who were periodically in touch with the Guardians; Marian Keech’s written messages were being supplemented that evening by “the Bertha,” a former beautician through whose tongue the “Creator” gave instruction. They rehearsed their lines diligently, calling out in chorus the responses to be made before entering the rescue saucer: “I am my own porter.” “I am my own pointer.” They discussed seriously whether the message from a caller identifying himself as Captain Video—a TV space character of the time—was properly interpreted as a prank or a coded communication from their rescuers.

In keeping with the admonition to carry nothing metallic aboard the saucer, the believers wore clothing from which all metal pieces had been torn out. The metal eyelets in their shoes had been ripped away. The women were braless or wore brassieres whose metal stays had been removed. The men had yanked the zippers out of their pants, which were supported by lengths of rope in place of belts.

The group’s fanaticism concerning the removal of all metal was vividly experienced by one of the researchers who remarked, 25 minutes before midnight, that he had forgotten to extract the zipper from his trousers. As the observers tell it, “this knowledge produced a near panic reaction. He was rushed into the bedroom where Dr. Armstrong, his hands trembling and his eyes darting to the clock every few seconds, slashed out the zipper with a razor blade and wrenched its clasps free with wirecutters.” The hurried operation finished, the researcher was returned to the living room—a slightly less metallic but, one supposes, much paler man.

As the time appointed for their departure grew very close, the believers settled into a lull of soundless anticipation. Luckily, the trained scientists gave a detailed account of the events that transpired during this momentous period.

The last ten minutes were tense ones for the group in the living room. They had nothing to do but sit and wait, their coats in their laps. In the tense silence two clocks ticked loudly, one about ten minutes faster than the other. When the faster of the two pointed to twelve-five, one of the observers remarked aloud on the fact. A chorus of people replied that midnight had not yet come. Bob Eastman affirmed that the slower clock was correct; he had set it himself only that afternoon. It showed only four minutes before midnight.