Influence: Science and Practice (39 page)

Read Influence: Science and Practice Online

Authors: Robert B. Cialdini

Hardly. The relationship between sport and earnest fan is anything but game-like. It is serious, intense, and highly personal. An apt illustration comes from one of my favorite anecdotes. It concerns a World War II soldier who returned to his home in the Balkans after the war and shortly thereafter stopped speaking. Medical examinations could find no physical cause for the problem. There was no wound, no brain damage, no vocal impairment. He could read, write, understand a conversation, and follow orders. Yet he would not talk—not for his doctors, not for his friends, not even for his pleading family.

Perplexed and exasperated, his doctors moved him to another city and placed him in a veterans’ hospital where he remained for 30 years, never breaking his self-imposed silence and sinking into a life of social isolation. Then one day, a radio in his ward happened to be tuned to a soccer match between his hometown team and a traditional rival. When at a crucial point of play the referee called a foul against a player from the mute veteran’s home team, he jumped from his chair, glared at the radio, and spoke his first words in more than three decades: “You dumb ass!” he cried. “Are you trying to

give

them the match?” With that, he returned to his chair and to a silence he never again violated.

There are two important lessons to be derived from this true story. The first concerns the sheer power of the phenomenon. The veteran’s desire to have his hometown team succeed was so strong that it alone produced a deviation from his solidly entrenched way of life. The second lesson reveals much about the nature of the union of sports and sports fans, something crucial to its basic character: It is a personal thing. Whatever fragment of an identity that ravaged, mute man still possessed was engaged by soccer play. No matter how weakened his ego may have become after 30 years of wordless stagnation in a hospital ward, it was involved in the outcome of the match. Why? Because he, personally, would be diminished by a hometown defeat, and he, personally, would be enhanced by a hometown victory. How? Through the principle of association. The mere connection of birthplace hooked him, wrapped him, tied him to the approaching triumph or failure.

As distinguished author Isaac Asimov (1975) put it in describing our reactions to the contests we view, “All things being equal, you root for your own sex, your own culture, your own locality . . . and what you want to prove is that

you

are better than the other person. Whomever you root for represents

you

; and when he [or she] wins,

you

win.” When viewed in this light, the passion of a sports fan begins to make sense. The game is no light diversion to be enjoyed for its inherent form and artistry. The self is at stake. That is why hometown crowds are so adoring and, more tellingly, so grateful toward those regularly responsible for home-team victories. That is also why the same crowds are often ferocious in their treatment of players, coaches, and officials implicated in athletic failures.

9

9

Take, for example, the case of Andres Escobar who, as a member of the Colombian national team, accidentally tipped a ball into his own team’s net during a World Cup soccer match in 1994. The “auto-goal” led to a U.S. team victory and to the elimination of the favored Colombians from the competition. Back home two weeks later, Escobar was executed in a restaurant by two gunmen, who shot him 12 times for his mistake.

So we want our affiliated sports teams to win to prove our own superiority, but to whom are we trying to prove it? Ourselves, certainly, but to everyone else, too. According to the association principle, if we can surround ourselves with success that we are connected with in even a superficial way (for example, place of residence), our public prestige will rise.

All this tells me is that we purposefully manipulate the visibility of our connections with winners and losers in order to make ourselves look good to anyone who views these connections. By showcasing the positive associations and burying the negative ones, we are trying to get observers to think more highly of us and to like us more. There are many ways we go about this, but one of the simplest and most pervasive is in the pronouns we use. Have you noticed for example, how often after a home-team victory fans crowd into the range of a TV camera, thrust their index fingers high, and shout, “We’re number one! We’re number one!” Note that the call is not “They’re number one” or even “Our team is number one.” The pronoun is

we

, designed to imply the closest possible identity with the team.

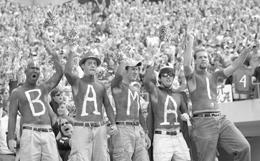

Sports Fan(atic)s

Team spirit goes a step beyond wearing the school sweatshirt as these Alabama students wear their school letters a different way and cheer their team to victory.

Note also that nothing similar occurs in the case of failure. No television viewer will ever hear the chant, “We’re in last place! We’re in last place!” Home-team defeats are the times for distancing oneself. Here

we

is not nearly as preferred as the insulating pronoun

they

. To prove the point, I once did a small experiment in which students at Arizona State University were phoned and asked to describe the outcome of a football game their school team had played a few weeks earlier (Cialdini et al., 1976). Some of the students were asked the outcome of a certain game their team had lost; the other students were asked the outcome of a different game—one their team had won. My fellow researcher, Avril Thorne, and I simply listened to what was said and recorded the percentage of students who used the word

we

in their descriptions. When the results were tabulated, it was obvious that the students had tried to connect themselves to success by using the pronoun

we

to describe their school-team victory—“We beat Houston, 17 to 14,” or “We won.” In the case of the lost game, however,

we

was rarely used. Instead, the students used terms designed to keep themselves separate from their defeated team—“They lost to Missouri, 30 to 20,” or “I don’t know the score, but Arizona State got beat.” Perhaps the twin desires to connect ourselves to winners and to distance ourselves from losers were combined consummately in the remarks of one particular student. After dryly recounting the score of the home-team defeat—“Arizona State lost it, 30 to 20”—he blurted in anguish, “

They

threw away

our

chance for a national championship!”

The tendency to trumpet one’s links to victors is not unique to the sports arena. After general elections in Belgium, researchers looked to see how long it took homeowners to remove their lawn-signs favoring one or another political party. The better the election result for a party, the longer homeowners wallowed in the positive connection by leaving the signs up (Boen et al., 2002).

Although the desire to bask in reflected glory exists to a degree in all of us, there seems to be something special about people who would take this normal tendency too far. Just what kind of people are they? Unless I miss my guess, they are not merely great sports aficionados; they are individuals with hidden personality flaws: poor self-concepts. Deep inside is a sense of low personal worth that directs them to seek prestige not from the generation or promotion of their own attainments but from the generation or promotion of their associations with others’ attainments. There are several varieties of this species that bloom throughout our culture. The persistent name-dropper is a classic example. So, too, is the rock-music groupie, who trades sexual favors for the right to tell friends that she or he was “with” a famous musician for a time. No matter which form it takes, the behavior of such individuals shares a similar theme—the rather tragic view of accomplishment as deriving from outside the self.

READER’S REPORT 5.3

From a Los Angeles Movie Studio Employee

Because I work in the industry, I’m a huge film buff. The biggest night of the year for me is the night of the Academy Awards. I even tape the shows so I can replay the acceptance speeches of the artists I really admire. One of my favorite speeches was what Kevin Costner said after his film

Dances with Wolves

won best picture in 1991. I liked it because he was responding to critics who say that the movies aren’t important. In fact, I liked it so much that I copied it down. But there is one thing about the speech that I never understood before. Here’s what he said about winning the best picture award:

“While it may not be as important as the rest of the world situation, it will always be important to us. My family will never forget what happened here; my Native American brothers and sisters, especially the Lakota Sioux, will never forget, and the people I went to high school with will never forget.”

OK, I get why Kevin Costner would never forget this enormous honor. And I also get why his family would never forget it. And I even get why Native Americans would remember it, since the film is about them. But I never understood why he mentioned the people he went to high school with. Then, I read about how sports fans think they can “bask in the reflected glory” of their hometown stars and teams. And, I realized that it’s the same thing. Everyone who went to school with Kevin Costner would be telling everyone about their connection the day after he won the Oscar, thinking that they would get some prestige out of it even though they had zero to do with the film. They would be right, too, because that’s how it works. You don’t have to be a star to get the glory. Sometimes you only have to be associated with the star somehow. How interesting.

Author’s note:

I’ve seen this sort of thing work in my own life when I’ve told architect friends that I was born in the same place as the great Frank Lloyd Wright. Please understand, I can’t even draw a straight line; but I can see the favorable reaction in my friends’ eyes. “Wow,” they seem to say, “You and Frank Lloyd Wright?”

Certain of these people work the association principle in a slightly different way. Instead of striving to inflate their visible connections to others of success, they strive to inflate the success of others they are visibly connected to. The clearest illustration is the notorious “stage mother,” obsessed with securing stardom for her child. Of course, women are not alone in this regard. A few years ago, a Davenport, Iowa, obstetrician cut off service to the wives of three school officials, reportedly because his son had not been given enough playing time in school basketball games. One of the wives was eight months pregnant at the time.

Defense

Because liking can be increased by many means, a list of the defenses against compliance professionals who employ the liking rule must, oddly enough, be a short one. It would be pointless to construct a horde of specific countertactics to combat each of the countless versions of the various ways to influence liking. There are simply too many routes to be blocked effectively with such a one-on-one strategy. Besides, several of the factors leading to liking—physical attractiveness, familiarity, association—have been shown to work unconsciously to produce their effects on us, making it unlikely that we could muster a timely protection against them anyway.

Instead we need to consider a general approach, one that can be applied to any of the liking-related factors to neutralize their unwelcome influence on our compliance decisions. The secret to such an approach may lie in its timing. Rather than trying to recognize and prevent the action of liking factors before they have a chance to work on us, we might be well advised to let them work. Our vigilance should be directed not toward the things that may produce undue liking for a compliance practitioner but toward the fact that undue liking has been

produced

. The time to call out the defense is when we feel ourselves liking the practitioner more than we should under the circumstances.

By concentrating our attention on the effects rather than the causes, we can avoid the laborious, nearly impossible task of trying to detect and deflect the many psychological influences on liking. Instead, we have to be sensitive to only one thing related to liking in our contacts with compliance practitioners: the feeling that we have come to like the practitioner more quickly or more deeply than we would have expected. Once we

notice

this feeling, we will have been tipped off that there is probably some tactic being used, and we can start taking the necessary countermeasures. Note that the strategy I am suggesting borrows much from the jujitsu style favored by the compliance professionals themselves. We don’t attempt to restrain the influence of the factors that cause liking. Quite the contrary. We allow those factors to exert their force, and then we use that force in our campaign against those who would profit by them. The stronger the force, the more conspicuous it becomes and, consequently, the more subject to our alerted defenses.