Insectopedia (33 page)

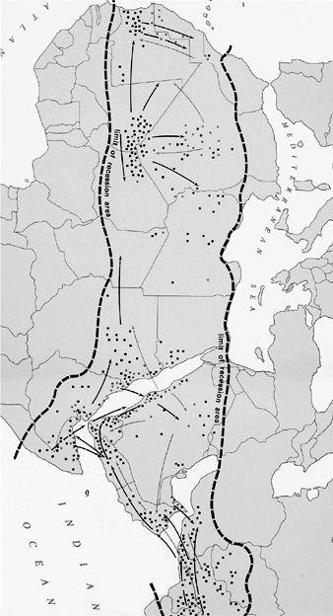

In fact, the professor went on, if you examine the desert locust atlas and look closely at the maps of the insect’s recession area—the zone in which it breeds and aggregates, the zone from which the swarms set out for pastures wetter and greener, a zone that covers about 6 million square miles in a broad belt that runs across the Sahel and through the Arabian Peninsula as far as India, and the only zone in which there is perhaps some slim chance of controlling the animal’s development—you’ll see clearly that many of the most important sites are in places commonly rendered inaccessible by conflict: Mauritania, eastern Mali, northern Niger, northern Chad, Sudan, Somalia, Iraq, Afghanistan, western Pakistan. It’s an extensive, familiar, and in this context, deeply disheartening list.

Across campus, in the Faculty of Letters and Human Sciences, Professor Boureima Alpha Gado told a similar story. A historian, Professor Alpha Gado is a leading expert on the famines of the Sahel and the author of an authoritative text on the subject.

1

He described how he had used manuscripts from Timbuktu, the ancient center of Islamic and pre-Islamic learning, to determine occurrences of “

calamités

” dating to the

mid-sixteenth century. For twentieth-century disasters, he collected oral histories from villagers, constructing a chronology of the major famines and identifying the critical factors—primarily drought, locusts, and changes in the agricultural economy—and their shifting interactions.

Professor Alpha Gado’s research revealed a rural society grappling with deeply founded insecurities, vulnerable to the vicissitudes of rainfall, human and animal epidemics, and upsurges in insect life. His work invigorated the truism that “natural disasters” act on already-existing social vulnerabilities and inequalities and that “nature” itself (driven in this case by desertification and climate-change-induced drought) is far from innocently natural. He carefully detailed the local social dimensions of these events: the colonial and postcolonial policies that increased the susceptibilities of people in the countryside to famine and reduced their resilience to insect invasions and disease. Notwithstanding the small number of all-too-brief interludes of relative prosperity, he described an everyday state of attrition interrupted by periods of catastrophe, in which the number of deaths has been “incalculable.” Like Mahamane Saadou, he painted a picture of overlapping terrors, of a persistent teetering on the brink, more a condition than an event, a condition with its own rhythms, histories, and enduring effects.

Locusts appear twice in

Things Fall Apart

, Chinua Achebe’s famous 1958 novel of British colonialism’s explosion of rural life in the late-nineteenth-century Niger Delta. The first time, “a shadow fell on the world, and the sun seemed hidden behind a thick cloud.” The village of Umuofia stiffens in anticipation of the darkness engulfing the horizon. Or does it?

Okonkwo looks up from his work and wonders if it is going to rain at such an unlikely time of year. But almost immediately a shout of joy breaks out in all directions, and Umuofia, which has dozed in the noonday haze, bursts into life and activity.

“Locusts are descending” is joyfully chanted everywhere, and men, women, and children leave their work or their play and run into the open to see the unfamiliar sight. The locusts have not come for a very long time, and only the old people have seen them before.

At first, there are not so many, “they were the harbingers sent to survey the land.” But soon a vast swarm fills the air, “a tremendous sight, full of power and beauty.” To the entire village’s delight, the locusts decide to stay. “They settled on every tree and on every blade of grass; they settled on the roofs and covered the bare ground. Mighty tree branches broke away under them, and the whole country became the brown-earth colour of the vast, hungry swarm.”

2

The next morning, before the sun has a chance to warm the animals’ bodies and release their wings, everyone is outside filling bags and pots, gathering all the insects they can hold. The carefree days that follow are filled with feasting.

But Chinua Achebe’s story is a tale of destruction. Joy becomes unrelenting historical pain. The cloud still looms, and its shadow falls over Umuofia’s future. Pleasures are bound fast to their fatal opposites. Everyone in the village is happily enjoying the unexpected harvest when a delegation of elders arrives at Okonkwo’s compound. Solemnly, the elders decree the killing of the beloved child who is Okonkwo’s ward, a killing that corrodes his family. Years later, when the locusts reappear, Okonkwo is in exile.

It is his friend Obierika who visits him with the news. A white man

has appeared in a neighboring village. “An albino,” suggests Okonkwo. No, he is not an albino. “The first people who saw him ran away,” says Obierika. “The elders consulted their Oracle and it told them the strange man would break their clan and spread destruction among them.” He continues, “I forgot to tell you something else the Oracle said. It said that other white men were on their way. They were locusts, it said, and that first man was their harbinger sent to explore the terrain. And so they killed him.”

3

They kill him, but it is too late. The vast swarm of white men would soon arrive. There’s no ambiguity in this story. The pleasures are quickly excised. It’s all flat, the flatness of history foretold. The flattening of everyday life among the locusts. Hard to think past these terrors, you might say (with reason). A vast swarm would soon come, and nothing would again be the same.

Mahaman and Antoinette are such good hosts! We’re sitting in their luxuriant tropical yard in Niamey talking about

les criquets.

We’re trying to specify the exact category of food in which they belong. Everyone agrees they’re a special food. But they’re a special kind of special food, different from the special crispy honey cakes Mahaman just brought back from Ethiopia and insists that Karim and I eat more of.

Criquets

are a social food, Antoinette says. Sort of like peanuts, but not a party food. Hmmm. A short silence. Well, texture is important: They’re crunchy! And they’re spontaneous, too. How so? Well, we shop in the open-air markets here, not in the supermarket, so we shop every day. It’s an every-day economy. We see

criquets

on the market and maybe we think, I’m going to buy some of them! We bring them home and cook them with oil, chilies, and plenty of salt. Sooo

delicious!

It’s a spontaneous treat. It’s a food for fun, a fun food, a personal, friendly treat. Friends, family. Social food. It’s the kind of food you eat just because you feel like eating it.

It’s a Nigerien food, adds Mahaman. When our daughter is at school in France, she always asks us to send her

criquets.

It’s the thing she misses most, the strongest taste of home. Yes, Karim agrees, it’s what

everyone misses; we sent packages to my sister when she was in France as well. And don’t you remember, he asks me, that’s what the guy this morning selling those rust-colored, crunchy-looking insects on the sleepy market just past the university said too? Fry some in salt and take them back to New York, he said; share them with a homesick Nigerien and make him very happy!

Talking like this, we quickly establish that—like so many foods

—criquets

satisfy spiritual as well as physical hungers. Eating them is one of those things that makes someone Nigerien. They eat them in Chad too, says Karim, but the quality is not so good. And no one eats them in Burkina, although Nigerien students bring packages from home across the border, and people in Ouaga are starting to get a taste for them. But Tuaregs don’t eat them, someone says, further complicating the national question. And, entering right on cue, closing the garden gate behind him with a broad smile, the director of LASDEL, the research institute that is hosting my stay, says yes, that’s right, we Tuaregs don’t eat small animals at all!

A special food, we all agree, and in the markets in Niamey and Maradi, this is obvious. The United Nations calculates that 64 percent of the population of Niger lives on less than the equivalent of U.S. $1 per day. The regime struggles to maintain its position at the helm of the state. How can the administration capture the resources it needs to maintain its popular base when 50 percent of its potential annual budget goes directly to the international development organizations? The government disputes the U.N. figures, as well as the 2008 human development index score of 0.370, which placed Niger 174th out of the 179 countries measured, as well as the Save the Children Mothers’ Index of 2009, which ranked the country 158 out of the 158 countries surveyed and cited 44 percent of its children as malnourished, the life expectancy of its women at fifty-six years, and a figure of one in six for the number of its infants expected to die before their fifth birthday. In the media, those numbers are taken to be both a national shame and—more assertively—an expression of international hostility.

4

Yet, however you look at it, in this situation the rhetoric of crisis does not work to the government’s advantage. Some of those figures may be debatable in a largely rural and far from straightforwardly cash-based economy. But it’s abundantly

clear that few people outside development workers, successful merchants, and the political class have much income to circulate.

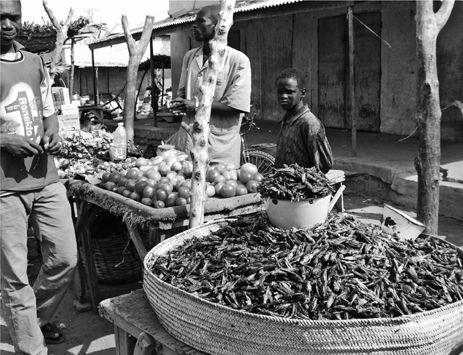

Nonetheless, in January 2008 traders in Niamey’s many markets were selling enamel basins of dried

criquets

for 1,000 CFA each, well over double the United Nations’ estimate of most people’s daily income.

5

Criquets

are a special food. And an expensive one, too.

January is not a good month in this business. With Eid al-Adha falling in early December this year and then Christmas and the celebration of the new year, there’s little extra cash for

criquets

, and people buy only in small amounts, just fractions of the enamel

tia

measuring bowl. It’s not only money that’s tight. There aren’t many insects in circulation either. January turns out to be a long way from September, when supply peaks at the end of the rainy season and the markets are full of locust sellers and the price falls as low as 500 CFA. Now, as we soon find out,

criquets

are scarce in the villages, and in another month no one will be bringing them into town.

We talked to all the insect-selling stallholders we could find in

Niamey. Some of them buy their stock in nearby market towns like Filingué and Tillabéri, some buy from traders on larger markets in Niamey, and some simply buy wholesale from neighboring stalls in the same market. Most, though, said their

criquets

come from Maradi, and all of them told us to go there. That’s where these animals are sent from, that’s where you’ll find the collectors out in the bush early in the morning, that’s where the big suppliers are based.

I’m enjoying running around Niamey with Karim. There’s so much to see and learn here. I love the markets, discovering with a shock that I recognize only a tiny proportion of the vegetables. These plants got here through an evolutionary history I can’t begin to imagine! And then there are products for sale that might equally be animal, vegetable, or mineral for all I can tell. I can’t come close to guessing their purpose until Karim explains that these neatly stacked mottled-glass marbles are globules of tree resin, which make a superior chewing gum; that those dark, craggy tennis balls are crushed and compressed peanuts used for sauce; that those bottles of murky liquid are full of contraband gasoline smuggled in from Nigeria.

Karim and I keep each other busy visiting the markets, the university, and government offices, meeting all kinds of interesting people, not just scholars and traders but state officials, development workers, insect scientists, insect eaters, and talkative fellow passengers in communal taxicabs. We make the most of Mahaman and Antoinette’s hospitality. But this can’t last. After just a few days, we find ourselves huddling in the crowded bus station at 3:30 a.m. We’re cold, sleepy, and a little bad tempered, and it feels as though the bus to Maradi will never arrive.