Insectopedia (37 page)

The drive back to Maradi is uneventful. Before we leave, the woman who had begun boiling the

houara

is called back to spread them on a blue tarpaulin so we can watch them dry in the sun. Zabeirou declares himself satisfied with the day’s program. As we approach the city, he asks if I’ll be back soon. I can’t offer a date, and we all slip into our own thoughts. When we reach Zabeirou’s house, his demeanor changes abruptly. Eschewing conventional sentimentalities, he demands payment for his services, apparently forgetting that our outing was conceived under the banner of international friendship and that he has already done rather well from the women of Dandasay. Karim is infuriated, and we enter into testy negotiations, Zabeirou refusing to let us leave until an unhappy compromise is reached.

The three of us drive back across town feeling irritable. But the mood doesn’t last long. Our sense of purpose returns when we decide to follow

Kommando’s advice and head out early the next morning for Dan mata Sohoua.

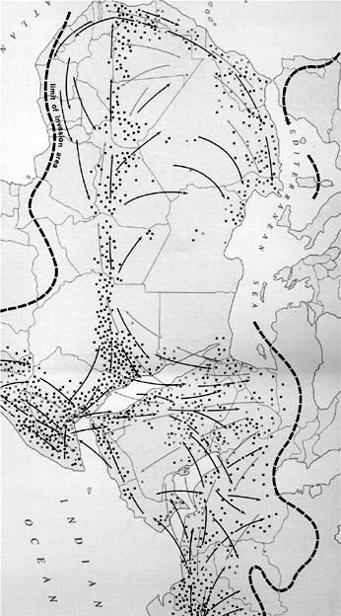

According to the World Bank, the invasion area of the

criquet pèlerin

extends over 20 percent of the earth’s farm- and pastureland, a total of 11 million square miles in sixty-five countries. Control measures, primarily surveillance and chemical spraying, focus on outbreak prevention and elimination in the recession area, the drier central zone of this region, the 6 million square miles within which the animals mass. The reasoning is simple: once the hopper bands have undergone their final molt to become winged adults and the swarm has taken to the air, the only option is crop protection through upsurge elimination on-site, an option with very low rates of success. Crop protection in the village, Professor Mahamane Saadou had told us, is a mark of the failure of prevention in the recession area. It means villages are saturated with pesticides—some that are banned in Europe and the United States—placing in jeopardy both the members of the village brigades who apply the chemicals (often

without protective clothing or adequate training) and the community’s food chain and water supply.

As Kommando had promised, the chief of Dan mata Sohoua was keen to tell the story. The locusts arrived from the west, he said. It was October, just after the rainy season. The millet was fully ripened, but the harvest had not yet begun, and the grain was still on the plants. The timing could not have been worse.

At first there were only a few, the harbingers—as Chinua Achebe has it—sent to survey the land. They appeared around midday. The children came running from the fields to raise the alarm. But none of the adults went to look. They knew it was already too late. By the time darkness fell, the swarm had arrived.

The next morning the village was overrun. The

houara

covered the ground. They covered the bush. You couldn’t see the ground. You couldn’t see the millet. People tried to chase them away. They used tools, they used their hands, they set fires. They tried to save the millet by picking it from the plant. What could they do but heap the seed heads on the ground? By the time they turned back, the insects were all over them.

On the morning of the second day, the

maigari

and a group of senior men went to Dakoro, the nearest town, to alert the Agricultural Service. Normally, the

maigari

told us, the Agricultural Service paid no attention to the problems here. But that day they came. After inspecting the fields, they advised people to pray. There was nothing else for it, they said.

Nonetheless, later that day a plane arrived to spray the area with pesticides. As it flew overhead, the

houara

took off. At first it seemed as if they were leaving the village, but instead they took aim at the plane. They flew straight for it, enveloping the cockpit, swarming over the wings, trying to force it up and away from the village. The pilot changed tactics. He couldn’t come in low. Instead, he tried to spray alongside the insects, but they scattered and the chemicals had little effect. The animals were disciplined and organized. It was as if they had a commander and were following orders.

As if they had a commander. Every day, they started work at exactly 8 a.m. No, not because it was cold before then. That’s what everyone thinks, that they were waiting for the heat to warm their wings. But, no, it was because they had their workday. Like white people. They started at 8 a.m., never earlier. As it got close to 8, they became restless and ready

to fly. The commander gave the order, and they began. When they took off, they flew low, scouring the ground for food, always ready to land. At 6 p.m., they stopped. Like an army with a commander. These animals were intelligent. It was as if they had binoculars. If they left anything, they turned around and came back for it. If one of them was injured, they turned around, came back, and ate their fallen comrade rather than leave it on the road.

There were people who set fire to them in the mornings as the

houara

massed there waiting for the order. It was a mistake. It was just a provocation. If they managed to kill a sackful like that, they could be sure that double that number would soon arrive to take their place. Everyone stopped going to the fields. When they went outside, they had to cover their faces. Adults stopped children from going into the bush.

On the third day, the locusts left. There was no more millet. They’d taken it all. But they’d left something of their own. Two weeks later, the eggs hatched, and the hoppers emerged from the ground. This time was far worse than before.

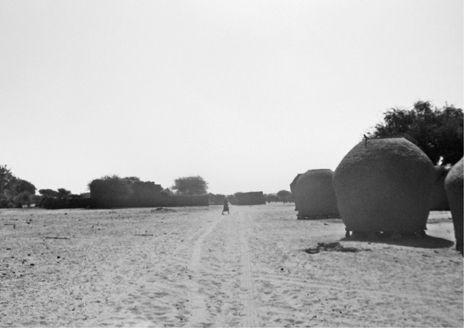

A small girl walked across the sand to where we were seated under a generous shade tree. The afternoon air was hot and still. In the distance, we could hear the rhythmic thuds of women pounding millet. The

maigari

sold the girl a few bouillon cubes. A thin-faced man seated behind a tabletop sewing machine picked up the story as the rest of us, six men and two women, listened.

We’d never seen these

houara

before, he said. Even people 100 years old had never seen them. We called them

houara dango

, destroyer crickets. They were bright yellow on the outside, black inside. The yellow came off like paint if you touched them. They were so strange that at first we thought they’d been invented by white people. The old people told the children not to touch them. The goats that ate them aborted, the chickens died. Not from the pesticides, as you might think, but from some tiny insects that lived inside the

houara.

The chickens and goats weren’t safe to eat. We had to destroy them. The

houara

entered the wells. They poisoned the water. Not even the cattle could drink from that water. Someone in another village ate them, and he was sick, vomiting for days. We couldn’t eat them. If we could, there were so many we’d be eating them still.

Now everyone was talking. There was no doubt that the second wave was even more devastating than the first. The Agricultural Service sprayed the hatchlings, but the survivors ate the corpses. There was nothing left in the fields. Whatever the hoppers could eat in the village, they ate. This time, they stayed for three weeks, working their way systematically through the village, consuming everything in their path, even their own dead; yes, that’s right, they left nothing, not even their own dead.

With no millet in the granaries and no harvest to look to, people in Dan mata Sohoua were completely dependent on emergency food aid. Fueled by emotionally charged reporting on the BBC, the situation in Niger and across the Sahel became international news. The specter of famine coupled with plagues of locusts prompted high-profile public appeals in the donor countries. These in turn generated dismayed reaction from the administration of Mamadou Tandja, who watched as this media-driven internationalization gave carte blanche to the nongovernmental organizations to act on behalf of a humanitarian global public, further undermining the state’s already-limited capacity.

For a few weeks, the Médecins Sans Frontières feeding center in Maradi “received more media attention than anywhere on the globe.”

23

And, indeed, although it is unclear how severe the situation was in other parts of Niger, for residents of the countryside around Maradi (and for pastoral people in the north), things were significantly more difficult than normal. Oxfam stepped in to Dan mata Sohoua with 400 bags of rice, which arrived just as everyone was debating whether to abandon the village. Dan mata Sohoua became a center of food distribution for people who arrived from all around to collect their ration. Oxfam promised three full consignments, but for reasons unknown to people here, the second delivery was much reduced and the third simply didn’t materialize.

That year of the

houara dango

, farmers in Dan mata Sohoua had planted seed lent by development organizations as an advance against their crop. When the millet failed, they had few options. One was to appeal to local merchants—from a position of extreme weakness—to convert donated rice to cash to meet their debt. But the rice never came, so the debts deepened (and people were unable even to sell their food aid, a practice that, although reviled by the aid agencies as profiteering, can have its own compelling logic).

Two harvests later, people told us, they still hadn’t repaid the loans. Nor had they paid their taxes since 2005. Just as the Nigerien state is caught in its chronic international dependencies, so people in the countryside around Maradi struggle to access whatever resources might come their way.

24

In the long days of hunger after the invasion, farmers in Dan mata Sohoua joined with NGOs in the region to start a

banque céréalière

, taking grain (rather than seed) on loan and repaying the loan after the harvest. Even in the best of times, the harvest provides little surplus, so the obligation to give some of it away is not a welcome one. But at least in this arrangement there is no need for cash—or for a Zabeirou. Perhaps, says someone wistfully, if the harvests are good, if no more swarms arrive, we’ll be out of this hole in another two years.

On the bus back from Maradi, Karim and I found ourselves sitting with a group of agronomists headed to Niamey for a conference on insect-pest management. They shared with us their ridged sheets of

tchoukou—

tangy crispy-chewy cheese—and when we all got down to stretch our legs at Birni N’Konni they insisted on paying for sodas. We talked about their work with resistant strains of millet, and I thought back to the conversation Karim and I had a few days before with an enthusiastic young researcher at the Maradi Direction de la protection des végétaux who is developing a biological control of the

criquet pèlerin

using pathogenic fungi as an alternative to chemical pesticides.

The next morning we went back to the university to visit Professor Ousmane Moussa Zakari, a prominent Nigerien biologist critical of the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization’s efforts at pest control. The FAO has never successfully predicted an invasion of the

criquet pèlerin

, Professor Zakari said. He calculates that there have been thirteen major locust outbreaks in Niger since 1780, and although the local effects can be overwhelming, the aggregate is less so. Like many of the researchers and farmers we talked to, he regards current control efforts as a failure. The recession area is too large and too inaccessible, the insects are too adaptable, capable of withstanding extended drought and responding rapidly to favorable conditions. He argued that the hundreds of millions of dollars spent on eradication would be better spent elsewhere, helping farmers draw on their own knowledge of pest control, for example, and working with them to develop new techniques, such as interrupting the development of the

criquet sénégalais

by delaying the planting of the first of the two annual crops of millet.

That same day, as if in a reminder of the complex fragilities with which Nigeriens struggle, a French aid worker was caught in a carjacking in Zinder. She had stopped her vehicle for two men who appeared to need help at the side of the road. They bundled her out of the car and drove off. No one was hurt, but unfortunately for everyone involved, the men had left without realizing that the woman’s toddler was still in the vehicle’s backseat.