Insectopedia (66 page)

18.

Robert L. Backus, trans.,

The Riverside Counselor’s Stories: Vernacular Fiction of Late Heian Japan

(Palo Alto, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1985), 53. I have incorporated Haruo Shirane’s amendment into Backus’s translation; see his review of

The Riverside Counselor’s Stories

in the

Journal of Japanese Studies

13, no. 1 (1987): 165–68.

19.

Maria Sibylla Merian,

Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium

, quoted in Schmidt-Lisenhoff, “Metamorphosis of Perspective,” 218.

20.

Franz Kafka, “A Report to the Academy,” in

The Transformation and Other Stories

, trans. Malcolm Pasley (London: Penguin, 1992), 187, 190.

Language

1.

The quotation can be found in James L. Gould’s

Ethology: The Mechanisms and Evolution of Behavior

(New York: W. W. Norton, 1982), 4. Without writing directly on von Frisch, Eileen Crist has also drawn attention to this rhetorical and epistemological shift from natural history to classical ethology. My reading of von Frisch locates him as something of a transitional figure in her schema between Jean-Henri Fabre (writing in what Crist calls the

Verstehen

tradition of animal studies, a hermeneutic ethology) and the new objectivism of Lorenz and Tinbergen. See Crist, “Naturalists’ Portrayals of Animal Life: Engaging the

Verstehen

Approach,”

Social Studies of Science

26, no. 4 (1996): 799–838; and Christ, “The Ethological Constitution of Animals as Natural Objects: The Technical Writings of Konrad Lorenz and Nikolaas Tinbergen,”

Biology and Philosophy

13, no. 1 (1998): 61–102.

2.

An argument first elaborated by Darwin himself in

The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex

(1871) and

The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals

(1872). For a useful discussion, see Carl N. Degler,

In Search of Human Nature: The Decline and Revival of Darwinism in American Social Thought

(Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 1991).

3.

On Clever Hans, see Vicki Hearne,

Adam’s Task: Calling Animals by Name

(New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1986). In regard to the impact of this episode on ethology, “the analysis of learning was limited to simple S-R (stimulus-response) associations; hypothesizing the existence of higher-level cognitive activities in animals was scrupulously avoided … until the 1960s and 1970s.” James L. Gould and Carol Grant Gould,

The Honey Bee

(New York: Scientific American, 1988), 216.

4.

Karl von Frisch,

A Biologist Remembers

, trans. Lisbeth Gombrich (Oxford, U.K.: Pergamon Press, 1967), 149.

5.

Ibid.

6.

On this, see Ute Deichmann,

Biologists under Hitler

, trans. Thomas Dunlap (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1996), 10–58.

7.

Von Frisch,

A Biologist Remembers

, 71.

8.

Ibid., 57.

9.

Ibid., 72–73.

10.

James L. Gould and Carol Grant Gould,

Honey Bee

, 58.

11.

In his monumental history of the early ethologists, Richard Burkhardt quotes a passage from von Frisch’s

Du und das Leben

(

You and Life

), a popular biology text published in 1938 in a series sponsored by Goebbels. Burkhardt writes that von Frisch “concluded the book with a section on race hygiene, voicing there the familiar warning that the relaxation of natural selection in higher cultures was leading to the perpetuation of variations that in the wild would have been ‘mercilessly weeded out.’ … This amounted in effect, he said, to an ‘encouragement of the inferior,’ or, as he put it more bluntly, ‘A tub of lard or a blind man finds his table as well set as any other person.’” Richard W. Burkhardt, Jr.,

Patterns of Behavior: Konrad Lorenz, Niko Tinbergen, and the Founding of Ethology

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), 248.

12.

Von Frisch,

A Biologist Remembers

, 129–30; Deichmann,

Biologists under Hitler

, 45–46.

13.

Von Frisch,

A Biologist Remembers

, 25.

14.

Ibid., 141. See also von Frisch,

The Dance Language and Orientation of Bees

, trans. Leigh E. Chadwick (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1993), 4–5.

15.

Terrence W. Deacon,

The Symbolic Species: The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain

(New York: W. W. Norton, 1997), 71. Deacon provides an extended gloss on the linguistics of Charles Sanders Peirce. Although Deacon prefers to reserve symbolic reference for humans, it seems clear that the bee dances meet the particular criteria that he outlines at this point.

16.

Donald R. Griffin,

Animal Minds: Beyond Cognition to Consciousness

, rev. edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 190. The following account of bee “language” is drawn from a number of sources in addition to Griffin’s excellent synthesis. These include three works by von Frisch:

The Dancing Bees: An Account of the Life and Senses of the Honey Bee

, trans. Dora Isle and Norman Walker (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1966);

Bees: Their Vision, Chemical Senses, and Language

(Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1950); and

Dance Language.

See also Thomas D. Seeley’s excellent foreword to

Dance Language;

Martin Lindauer,

Communication among Social Bees

(Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1961); Axel Michelson, Bent Bach Andersen, Jesper Storm, Wolfgang H. Kirchner, and Martin Lindauer, “How Honeybees Perceive Communication Dances, Studied by Means of a Mechanical Model,”

Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology

30 (1992): 143–50; Thomas D. Seeley,

The Wisdom of the Hive: The Social Physiology of Honey Bee Colonies

(Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995); and James L. Gould and Carol Grant Gould,

Honey Bee.

17.

Von Frisch,

Dance Language

, 57.

18.

Thomas Seeley suggests that it makes more sense to refer to all dances as waggle dances. Thomas D. Seeley, foreword to

Dance Language

, xiii.

19.

Von Frisch,

Dance Language

, 57.

20.

See, for example, Axel Michelson, William F. Towne, Wolfgang H. Kirchner, and Per Kryger, “The Acoustic Near Field of a Dancing Honeybee,”

Journal of Comparative Physiology A: Neuroethology, Sensory, Neural, and Behavioral Physiology

161

(1987): 633–43. Bee communication has actually turned out to be considerably more complex than even von Frisch imagined. In addition to this acoustical signaling, of which he was not aware, it now seems that the waggle dances are not internally consistent. When honeybees are dancing for a food source that is closer than about one mile, both the number of waggles and the direction of the straight run in each cycle show significant variation. Followers deal with this by staying with the dancer for multiple cycles, rapidly calculating a mean before flying off to the food source. James L. Gould and Carol Grant Gould,

Honey Bee

, 61–62.

21.

Von Frisch,

A Biologist Remembers

, 150.

22.

Von Frisch,

Dance Language

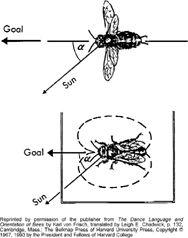

, 132, fig. 114. Von Frisch illustrates the behavior with this figure:

23.

Lindauer,

Communication among Social Bees

, 87–111, summarizes this material.

24.

I am not reviewing here the many variations that researchers have patiently documented. Lindauer (ibid., 94–96), for example, reveals that bees will compensate for side winds by altering the angle of flight, but on returning to the hive, they will indicate the optimal direction, not the actual route taken.

25.

But see Christoph Grüter, M. Sol Balbuena, and Walter M. Farina, “Informational Conflicts Created by the Waggle Dance,”

Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences

275 (2008): 1321–27, an important paper that reports on research suggesting that the vast majority of bees observing dances do not act on the information performed, preferring instead to return to familiar rather than new sources of food. Although the authors note that bees will switch contextually between “social information” (that is, from the dance) and “private information” (that is, about an already visited plot), they propose that dance data are most often acted on by bees who have been inactive for a while or are new to foraging. In what has become a familiar but revealing trope in insect studies more generally, they conclude that further research “will most certainly reveal that the waggle dance modulates collective foraging in more complex ways than is currently assumed.”

26.

These findings are among those vigorously challenged by Adrian Wenner and his collaborators, who for decades—though ultimately unsuccessfully—argued that

von Frisch’s claims were groundless. The controversy has generated a large literature. For a very useful account, see Tania Munz, “The Bee Battles: Karl von Frisch, Adrian Wenner and the Honey Bee Dance Language Controversy,”

Journal of the History of Biology

38, no. 3 (2005): 535–70.

27.

Von Frisch,

Dance Language

, 109–29.

28.

Ibid., 27.

29.

Von Frisch,

Bees

, 85.

30.

Von Frisch,

Dance Language

, 32, 37ff. Von Frisch’s bees even “give it up on the dance floor” (265), though it’s only fair to point out that—even though this is the 1970s—he’s talking here about water, not the spirit of disco.

31.

Ibid., 133, 136.

32.

Martin Lindauer, interview by Thomas D. Seeley, S. Kühnholz, and Robin H. Seeley, “An Early Chapter in Behavioral Physiology and Sociobiology: The Science of Martin Lindauer,”

Journal of Comparative Physiology A: Neuroethology, Sensory, Neural, and Behavioral Physiology

188 (2002): 441–42, 446.

33.

Lindauer, ibid., 445.

34.

Von Frisch,

Dancing Bees

, 1.

35.

Ibid., 41.

36.

Thomas D. Seeley,

Wisdom of the Hive

, 240–4.

37.

Lindauer,

Communication among Social Bees

, 16–21.

38.

This, of course, is also the narrative for the robotic assembly-line hive that appears in so many variants of social theory, for example, Marx’s famous fable of the architect: “What distinguishes the worst architect from the best of bees is this, that the architect raises his structure in imagination before he erects it in reality.” Karl Marx,

Capital: A Critique of Political Economy

, trans. Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr, 1921), 1:198. (My thanks to Don Moore for reminding me of this one.) There are only two clear examples of competition within the hive that I know of, both of which are of direct functional value to the colony. The first is the eviction of the drones, which I describe below; the second is the regulated fight for dominance among emerging queens after the nest has fissioned.

39.

Klaus Schlüpmann, “Fehlanzeige des Regimes in der Fachpresse?” [Negative Reports of the Regime in Specialist Publications] in

Vergangenheit im Blickfeld eines Physikers: Hans Kopfermann 1895–1963

[

History from the Viewpoint of a Physicist: Hans Kopfermann 1895–1963

], Aleph 99 Productions, September 20, 2002.

http://www.aleph99.org/etusci/ks/t2a5.htm

.