Insectopedia (7 page)

* * *

As with many repulsive tasks, once the shock of entering the field of action has passed, disgust generates an energy of its own. Partly, it’s the desire to finish rapidly. Partly, the activity itself blocks out reflection and produces a kind of drunkenness, a giddiness that sees off doubt.

I waded in. Thousands, tens of thousands of maggots, “slippery finger-length maggots,”

1

white maggots, writhing on the floor, shiny and wet. In an hour it was over: the room clean, the floor sluiced, the job still mine.

With careless hands a child kills an ant, many ants. Flies are far trickier, though once caught, they have little chance. And if darting birds don’t grab them first, butterflies die a natural death; few people—collectors excepted—willfully still such tremulous beauty.

* * *

It has the marks of permanent war. Beetles, good at hiding, keep close to the ground. Wisława Szymborska finds one dead on a dirt road, “three pairs of legs … neatly folded across its belly.” She stops and stares. “The horror of the site is moderate,” she writes. “Sorrow is not contagious.” But still doubt remains:

For our peace of mind, animals do not pass away,

but die a seemingly shallower death

losing—we’d like to believe—fewer feelings and less world,

exiting—or so it seems—a less tragic stage.

2

An uncommon sensibility. Almost like a child meeting death for the first time, grasping analogy, tentatively building a bridge. Tentatively. The poet is tentative. Her knowledge of the small (and sometimes large) acts of bad faith through which we live our lives is what makes the poem.

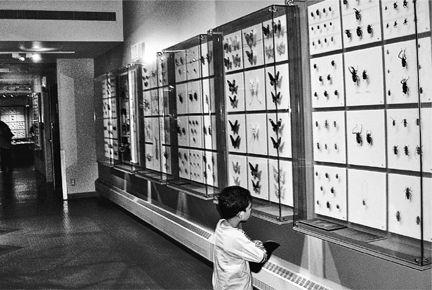

Three years ago, Sharon and I walked through the entrance doors of the Montreal Insectarium, down the curved staircase to the open-plan exhibition hall, and within minutes, were absorbed in the displays. All those insects in one place got us thinking about the megacategory the museum had taken on, about the unreachable diversity contained within that word

insects

, and about how unfortunate it is that the negative connotations

of the word sweep up so much. Such are the perils of taxonomy in the public sphere. And what a huge task it leaves a place like this.

* * *

But pretty soon, realizing that everyone else—people of all ages—was just as absorbed, we began thinking how well the curators, designers, educators, and other staff had succeeded in their mission to “encourage … visitors to think more positively about insects.” We were struck by the combination of exhibits on topics that are more familiar (insect biology) and less familiar (cultural connections between humans and insects). The exhibits were thoughtful and fun; the text was smart and didn’t talk down. The examples were diverse and intriguing.

And then, like a thought unthought, like that peculiar biblical image of scales falling from Saul’s eyes, like waking from a dream, like that moment when the drugs wear off (or, alternatively, when they kick in), we both realized, at what seemed like the exact same instant, that we were in a mausoleum and that the walls were lined with death, that those gorgeous pinned specimens, precisely arranged according to aesthetic

criteria—color, size, shape, geometry—were not just dazzling objects; they were also tiny corpses.

* * *

How strange that we look at insects as beautiful objects, that in death they are beautiful objects whereas in life, scuttling across the wooden floor, lurking in corners and under benches, flying into our hair and under our collars, crawling up our sleeves … Imagine the chaos if they came back to life. The impulse, even in this place, would be to lash out and crush them.

But if you watch people going from case to case around the room, you see right away that many of these objects (not necessarily the largest, not necessarily the ones with the longest legs or spindliest antennae) possess intense psychic power. It’s clear in the way that everyone—myself included—navigates the displays, in the way that we move along the rows a little tentatively and then pull up short and sometimes back off sharply. And it’s a little odd that we act like this, because the animal is not only locked behind Perspex in a display case but is, besides, not at all physically dangerous, if, in fact, it ever was. It is as though, along with their beauty, these animals find their way to some deep part of us and, in response, something taboo-like draws us in. Despite death, they enter our bodies and make us shiver with apprehension. What other animal has this power over us?

* * *

So much about insects is obscure to us, yet our capacity to condition their existence is so vast. Look closely at these walls. Even the most beautiful butterfly, observed Primo Levi, has a “diabolical, mask-like face.”

3

Unease has a stubborn source, unfamiliar and unsettling. We simply cannot find ourselves in these creatures. The more we look, the less we know. They are not like us. They do not respond to acts of love or mercy or remorse. It is worse than indifference. It is a deep, dead space without reciprocity, recognition, or redemption.

Flies, Saint Augustine wrote, were invented by God to punish man for his arrogance. Was that what the people of Hamburg were supposed to feel in 1943 as they stumbled through the smoldering ruins of their city during the pauses between Allied bombing raids? Flies—“huge and iridescent green, flies such as had never been seen before”—were so thick around the corpses in the air-raid shelters that, across the floors writhing with maggots, the work teams detailed to collect the dead could reach the bodies only by clearing the way with flamethrowers.

4

And then, here and elsewhere, on the heels of imposed vulnerability come the images of famine and disease, flies sipping from the corners of dull eyes, sucking at the edges of crusted mouths, crusted noses. Child and adult too weak, too pacified, to keep brushing them away. Animals, too, dogs, cows, goats, horses. Flies taking over, moving in, preparing the generations, the eggs, the larvae, the feast. Heralding the transition, only slightly premature.

volution

1.

“The maggot is a power in this world,” wrote Jean-Henri Fabre, the Insect Poet, in a moment of characteristic awe. He was philosophizing about flies—bluebottles, greenbottles, bumblebee flies, gray flesh flies—and their capacity “to purge the earth of death’s impurities and cause deceased animal matter to be once more numbered among the treasures of life.”

1

He was pondering the rhythm of the seasons and the cycles of mortality, and he was exploring the grounds of his new house in Sérignan du Comtat, a small village in Provence close to Orange where he was unearthing his own treasures: decaying bird corpses, fetid sewer ducts, ruined wasps’ nests—secret refuges of nature’s alchemy.

Fabre had called this house, with its large garden, l’Harmas (“the

name given, in this district, to an untilled, pebbly expanse abandoned to the vegetation of the thyme”), and it is now a national museum, recently reopened after six years’ renovation.

2

It is a beautiful house, large and imposing, glowing pink in the summer sunshine, thick walled to keep out the mistral, pale-green shutters. A handsome house that was known locally as

le château.

3

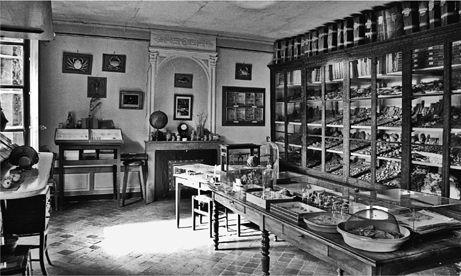

Fabre was fifty-six when he moved here. Almost immediately he had a two-story addition built onto the main residence: on the first floor, a greenhouse where he and his gardener grew plants for the grounds and for his botanical studies; above, a naturalist’s laboratory, in which he spent the greatest part of his time. The property is on the outskirts of Sérignan, and one of Fabre’s first acts was to surround its nearly two and a half acres with a stone wall six feet high, isolating it still further. Indeed, Anne-Marie Slézec, the director of the museum, told me, in his thirty-six years here, Fabre never once ventured the few hundred yards into the village.

Mme. Slézec had been assigned to l’Harmas from her position as a research mycologist at the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, and now, after six years in the provinces, her task complete, she was eagerly anticipating her return to Paris.

There was a good reason to select a mycologist for this posting: among the chief treasures of l’Harmas are 600 luminous aquarelles of local fungi, delicate portraits that Fabre painted in an effort to preserve the colors and substance of objects that, once collected, rapidly lost all relation to their living form. The paintings are justly famous, and they seem in some way to distill Fabre’s entire life’s work. Powerfully descriptive and immediately accessible, they strive to capture the ecological whole and, in doing so, to convey the beauty and what he saw as the mysterious perfection of nature. They are the product of exceptional observational skills. They utilize a talent that was largely self-taught. And they reveal a profound intimacy with their subject.

But Mme. Slézec’s task was to be less mycological than antiquarian. She rapidly turned detective. To reconstruct Fabre’s study, she hunted down old photographs, securing the crucial lead from a librarian in Avignon who found a contemporary image, which the director set out to reproduce in every respect. Somehow she turned up the very same framed pictures; the same books; the same clock (which she had restored

to working order); the same globe; the same chairs; the same cases of snails, fossils, and seashells; the same set of scales. She reinstated the famous writing desk, just two and a half feet long, a school desk really, insubstantial enough for Fabre to pick up and move as needed. She brought the photograph back to life. Or rather, she brought it into the present and, in the process, re-created the study as a memorial. Only Fabre himself is missing (and he is missing from the image, too), though the sunlight that still floods through the garden window fills the room with the aura of his life, a life lived fully right in this space.

The grounds presented a different challenge. When Fabre arrived, in 1879, he discovered that the nearly two and a half acres of land he now owned had once been a vineyard. Cultivation had involved the removal of most of the “primitive vegetation.” “No more thyme, no more lavender, no more clumps of kermes-oak,” he lamented.

4

Instead, his new garden was a mass of thistles, couch grass, and other upstarts. He ripped it out and replanted. By the time Mme. Slézec arrived, however, the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, which had taken possession on the death of Fabre’s last surviving son, in 1967, had turned much of the land into a botanical garden. Scouring Fabre’s notebooks, his manuscripts, and his correspondence, studying photographs taken on the

grounds, Mme. Slézec searched for clues that would enable her to restore what Fabre had intended to persist after his death. She cleared the shrubs obstructing his much-loved view of Mount Ventoux, the isolated outlier of the French Alps that—following in Petrarch’s famous footsteps—Fabre often climbed. She reintroduced bamboo, forsythia, roses, and Lebanon oak, and she protected and managed the surviving Atlas cedars, the Aleppo and Corsican pines, and the graceful lilac walk that leads from the entry gate to the house.