Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics (46 page)

Read Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics Online

Authors: Jonathan Wilson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

In Argentina, Riquelme is adored and despised in equal measure, the depth of feeling he provokes indicative of how central the playmaker is to Argentinian notions of football. The

enganche

, Asch wrote in a column in

Perfil

in 2007, is ‘a very Argentinian invention, almost a necessity’. The playmaker, he went on ‘is an artist, almost by definition a difficult, misunderstood soul. It would, after all, hardly seem right if our geniuses were level-headed’; it is as though they must pay a price for their gifts, must wrestle constantly to control and to channel them. Certainly there is that sense with Riquelme, who eventually frustrated the Villarreal coach Manuel Pellegrino to the extent that he exiled him from the club.

‘We are not,’ Asch wrote, ‘talking necessarily about a leader. Leaders were Rattín, Ruggeri, Passarella or Perfumo, intimidating people. No. Our man is a romantic hero, a poet, a misunderstood genius with the destiny of a myth… Riquelme, the last specimen of the breed, shares with Bochini the melancholy and the certainty that he only works under shelter, with a court in his thrall and an environment that protects him from the evils of this world.’ Perhaps, Asch said, he should never have left Boca.

Well, perhaps, but it is not that Riquelme cannot prosper away from the club he clearly adores. He struggled with Barcelona, but he was the major reason Villarreal reached a Champions League semi-final 2005-06, and his intelligence was central to Argentina’s sublime progress to the quarter-final of the World Cup later that summer. And yet he took blame for his sides’ exits from both competitions. He missed a penalty against Arsenal in the Champions League, and was withdrawn after seventy-two anonymous minutes against Germany. Some cited Riquelme’s supposed tendency to go missing in big games; but what is striking is that the coach, José Pekerman, replaced him not with a similar

fantasista

, despite having Messi and Saviola available, but with the far more defensive Estaban Cambiasso, as he switched to a straight 4-4-2. He either decided that Torsten Frings, the more defensive of the two German central midfielders in their 4-4-2, would get the better of any playmaker he put on, or, as many argued, he lost his nerve completely and lost faith in the formation because of Riquelme’s ineffectiveness. Little wonder that Riqelme has commented - as a matter of fact, rather than from bitterness - that when his side loses, it is always his responsibility.

And this, really, is the problem with a designated playmaker: he becomes too central. If a side has only one creative outlet, it is very easy to stifle - particularly when modern systems allow two holding midfielders without significant loss of attacking threat. That is true of the 4-3-1-2, its close cousin the diamond, and the 3-4-1-2. All three can also be vulnerable to a lack of width. Significantly, under Bielsa, not that Riquelme got much of a look in, Argentina played at times with a radically attacking 3-3-1-3, a formation almost unique at that level. Bielsa had already experimented with a 3-3-2-2, using Juan Sebastian Verón and Ariel Ortega behind Gabriel Batistuta and Claudio López, with Javier Zanetti and Juan Pablo Sorín as wing-backs and Diego Simeone as the holding midfielder in front of three central defenders. That was essentially a variant of the 3-4-1-2, with one of the central midfielders becoming an additional

trequartista

, but it was just as prone to the lack of width as the more orthodox version. Shifting one of the centre-forwards and one of the

trequartistas

wide and converting them into wingers, though, alleviated that. The playmaker was provided with a wealth of passing options and the formation was so unusual it was difficult to counter.

‘In the defensive phase,’ the Argentinian coach Cristian Lovrincevich wrote in

Efdeportes

, ‘the collective pressing method was adopted, with all lines pushing forwards to recover the ball as close as possible to the opposition goal. In essence it was very similar to the Total Football of the Dutch. In the offensive phase, once the ball had been recovered, the team tried to play with depth, avoiding unnecessary delays and the lateralisation of the game. In attack, five or six players were involved; only four positions were mainly defensive - the three defenders and the central midfielder.’

The problem with both variants, though, is that once possession is lost, regaining it can be difficult and the team is necessarily vulnerable to the counter. Argentina employed the 3-3-2-2 at the 2002 World Cup and, after the group stage, they had had more possession, created more chances and won more corners than any other side. Unfortunately they were also on their way home, having managed just two goals and four points from their three games, raising questions both about defensive weaknesses and about the quality of the chances created. When attacks are funnelled down the centre, the defending side can simply sit deep, watch the opponents pass the ball around in deep areas, and restrict them to long-range efforts. In the 4-3-1-2 or the 3-4-1-2, width can be provided by good movement from the forwards, or by the

carrileros

, the shuttling midfielders, pulling wide, or by attacking full-backs, but when the system goes wrong, the problem tends to be either lack of attacking width, or the holes left defensively by trying to provide it.

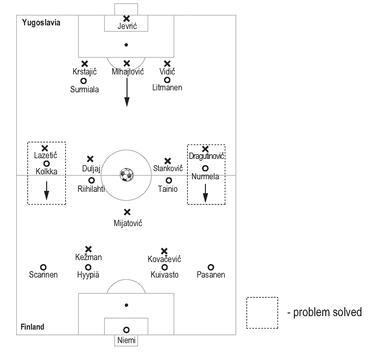

Yugoslavia 2 Finland 0, Euro 2004 qualifier, Marakana, Belgrade, 16 October, 2002

Second Half

Shakhtar Donetsk 2007-08

That is not to say that both formations are necessarily doomed, merely that they are restricted in their application. In October 2002, for instance, in a Euro 2004 qualifier in Naples, Yugoslavia fielded a flattened diamond to try to frustrate Italy. Goran Trobok sat in front of the back four, with Siniša Mihajlović to his left, Nikola Lazetić to his right, and Dejan Stanković as a deepish

trequartista

, with Predrag Mijatović dropping off Mateja KeŽman. Playing defensively, the plan worked as Alessandro Del Piero found his space restricted, and Yugoslavia arguably had the better of a 1-1 draw. At home in Belgrade against Finland four days later, though, Yugoslavia adopted a similar system and struggled. With the onus on them to create, rather than relying on breaks, they lacked attacking width, while they struggled defensively as their full-backs were repeatedly isolated against Mika Nurmela and Joonas Kolkka, the two wide players in Finland’s 4-4-2. At half-time it was 0-0, at which Yugoslavia switched to a 3-4-1-2, with Mihajlović stepping out from the back three to become an additional midfielder. Nurmela and Kolkka suddenly found themselves having to deal with wing-backs, which both gave them a defensive responsibility and diminished the space in which they had to accelerate before meeting a defender; Yugoslavia, with a spare man both in the middle at the back and in the middle of midfield, began to dominate possession, and ended up winning by a comfortable 2-0.

That, perhaps, is the major reason the diamond is slipping out of fashion. Of the thirty-two sides who reached the Champions League group stage in 2007-08, only Mircea Lucescu’s Shakhtar Donetsk deployed it in its classic form, and they ran into the classic problems. Particularly in their opening game, at home to Celtic, but also in their second, away to Benfica, they were superb, Razvan Rat and Darijo Šrna flying forward from full-back with the holding midfielder Mariusz Lewandowski dropping back to protect them (the diamond becoming effectively a 3-4-1-2), and the slight Brazilian Jádson operating as a playmaker behind a front two. In their next two games against AC Milan, though, their weakness high up the pitch in wide areas was exposed. They were well beaten in both and, as confidence waned, ended up failing to qualify even for the Uefa Cup.

Shifting to a 3-4-1-2 worked for Yugoslavia against Finland largely because it negated the impact of the opposing wingers, but it is just as liable to render a side one-dimensional, as Croatia found at the 2006 World Cup as they persisted with three at the back long after the rest of Europe had abandoned it. When they finished third at the World Cup in 1998, Ciro Blazević managed at times to squeeze three playmakers into their line-up. Fielding Zvonimir Boban, Robert Prosinečki and Aljosa Asanović together in central midfield defied logic - it was, as Slaven Bilić said, ‘the most creative midfield ever’ - and yet somehow it worked. That, though, was a one-off, aided by the fact that their back three included, in Bilić and Igor Štimac, two stoppers who were also comfortable on the ball plus either Dario Šimić or Zvonimir Soldo, both of them equally capable of playing in midfield, who would step out to become a midfielder when necessary. It is notable too that the 3-0 quarter-final victory over Germany, their best performance of the tournament, came when Prosinečki was absent, leaving Soldo to operate as a holding midfielder in what was effectively a 3-3-2-2 - another of those simple shifts of balance the 3-5-2 permits.

By the time of the 2006 World Cup, their coach Zlatko Kranjčar had gone down the route of Italy in the late nineties and decided that to play with an out-and-out playmaker in his son, Niko Kranjčar, it was necessary to bolster the midfield with two holding players - a formation not dissimilar to that adopted by West Germany in the latter stages of the 1986 tournament. However aggressive Šrna and Marko Babić were as wing-backs, it couldn’t disguise the fact that with Igor Tudor, often a centre-back with Juventus, and Niko Kovač, a more complete midfielder, but somebody who has become decreasingly creative as his career has gone on, at the back of the midfield, they were effectively playing with seven defenders.

That was enough to earn a battling 1-0 defeat to Brazil, but when Croatia had to take the initiative, as they did against Japan and Australia in their other two group games, they were tiresomely predictable, reliant for creativity either on the forward surges of the wing-backs, or on an out-of-sorts Kranjčar. They played stodgy, tedious football, and as their frustration got the better of them, they became over-physical and boorish. The only silver lining for Croatia was that Serbia-Montenegro had an even worse tournament, but their impressive qualifying performances, having switched away from the traditional Balkan three at the back, did not go unnoticed. In ten qualifying games they conceded only one goal, with their quartet of defenders - Goran Gavrančić, Mladen Krstajić, Nemanja Vidić and Ivica Dragutinović - attracting the nickname ‘the Fantastic Four’. Serbia-Montenegro could blame injuries and disintegrating team morale for their embarrassment in Germany; Croatia’s problems seemed to be rooted rather in the very way they played the game: Serbia had at least begun their process of evolution.

The debate about the merits of 3-5-2, or 3-4-1-2, had dogged Croatian football for years. Bilić ended it at a stroke when he replaced Zlatko Kranjčar as coach after the tournament. His side, he announced, would play four at the back, preferably, but not necessarily, in a Dutch-style 4-3-3. The fear among traditionalists was that that would mean the end of the playmaker, but Bilić found a way of accommodating not just one, but two. It might not have been quite the heady days of Blazević’s 3-3-2-2, but it was far better than anyone had hoped, far better than it had been during Kranjčar’s reign.