Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics (47 page)

Read Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics Online

Authors: Jonathan Wilson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

Bilić supplemented his back four with Niko Kovač as a deep-lying midfielder, and found room for not merely two forwards, but also Kranjčar on the left, with Luka Modrić in the middle, and Šrna on the right. With his slight, almost fragile build, Modrić resembles the traditional playmaker, but there is more to his game than that. ‘My role in the national team is very different to the one I perform with Dinamo,’ he said. ‘Here I have a freer role, but I also have more defensive responsibilities.’ Significantly, Zlatko Kranjčar had praised his ‘organisational’ qualities when he first called him into the national squad ahead of the World Cup.

1998 (3-0 v Germany, World Cup quarter-final, Stade Gerland, Lyon, 4 July 1998)

2006 (2-2 v Australia, World Cup Group Phase, Gottlieb-Daimler Stadium, Stuttgart, 22 June, 2006)

2007 (2-0 v Estonia, Euro 2008 qualifier, Maksimir, Zagreb, 8 September 2007)

Modrić and Niko Kranjčar represent the new style of playmakers -

fantasistas

with a certain robustness, and also a sense of tactical discipline. ‘Nobody wants playmakers, nobody buys them,’ Asch wrote. ‘Why? Do they hate poetry, do they hate colour?’ It comes back, it would seem, to Tomas Peterson’s point about a second order of complexity. Once the systems are understood, once football has lost its naivety, it is no longer enough simply to be beautiful; it must be beautiful within the system. ‘It happens that nobody in the world plays with a playmaker anymore,’ Asch went on. ‘Midfielders are multi-function and forwards are a blend of tanks and Formula One cars.’ Maybe so, and the playmaker will be missed, but just as the traditional winger was superseded and phased out by evolution, so too will be the traditional playmaker. Riquelme is a wonderful player. He may prosper at Boca, to whom he returned at the beginning of 2008. He may even prosper for Argentina, for international defences are not so well drilled as those at club level, but he is the last of a dying breed, a glorious anachronism.

The Nigerian cult of Kanu, which slightly mystifyingly sees him not as a second striker, as he has been used throughout his career in Europe, but as a

trequartista

, regularly forces him into the playmaking role for his country, but that has served only to highlight its redundancy. At Portsmouth, Kanu worked because he had in Benjani Mwaruwari a partner who charged about with an intensity that rather cloaked the intelligence of his movement. Benjani did the running while Kanu strolled around in the space between midfield and attack: one was energy, one was imagination, an almost absolute division of attributes that, at Portsmouth’s level at least, worked.

At the African Cup of Nations in 2006, Kanu was used to great effect as a substitute. Once the pace of the game had dropped, he would come on, find space and shape the game. Eventually, the pressure from the Nigerian press grew until their coach, Augustin Eguavoen, felt compelled to start him against Côte d’Ivoire in the semi-final. Kanu barely got a kick, shut out by the pace, power and nous of Côte d’Ivoire’s two holding midfielders, Yaya Touré and Didier Zokora. Two years later, in Nigeria’s opening game in Sekondi, their new coach, Berti Vogts, threw him into exactly the same trap. Against one anchor-man, perhaps Kanu could have imposed his will and thrived; against two, it was impossible. To say it is to do with his age is to miss the point. The playmaker belongs to an era of individual battles: if he could overcome his marker, he could make the play. Against a system that allows two men to be deployed against him, he can’t. Yes, by deploying two men against the playmaker the defensive side is potentially creating space for another, but zonal marking is designed to counter precisely that sort of imbalance. There exactly is the deficiency of the 4-3-1-2: stop the designated playmaker and the flow of creativity is almost entirely staunched.

So how then can a playmaker be used in the modern game? Early versions of Bilić’s system - such as that played by Croatia when they beat England 2-0 in Zagreb in October 2006 - included Milan Rapaić, a forward-cum-winger on the right; Šrna, as a wing-back who is also a fine crosser of the ball, gives them rather more balance. Still, Bilić’s Croatia employ five attacking players, something almost unique in the modern game, which may explain why they conceded three away to Israel and two at Wembley in qualifying for Euro 2008.

Using a single creator raises the danger of becoming one-dimensional, but there are other reasons why three at the back is declining in popularity in every major football country apart from Brazil. José Alberto Cortes, head of the coaching course at the University of São Paulo, believes the issue is physical. ‘With the pace of the modern game,’ he said, ‘it is impossible for wing-backs to function in the same way because they have to be quicker and fitter than the rest of the players on the pitch.’

Most others, though, seem to see the turn against three at the back as being the result of the effort to incorporate skilful players by bolstering the midfield. There is, of course, an enormous irony here, in that Bilardo’s formation in 1986 both popularised three at the back and included a playmaker as a second striker, the very innovation that has led ultimately to the decline of three at the back. Bilardo’s scheme had two markers picking up the opposing centre-forwards, with a spare man sweeping behind. If there is only one centre-forward to mark, though, that leaves two spare men - one provides cover; a second is redundant - which in turn means a shortfall elsewhere on the pitch. ‘There’s no point having three defenders covering one centre-forward,’ explained Miroslav Djukić, the former Valencia defender who became Partizan Belgrade coach in 2007.

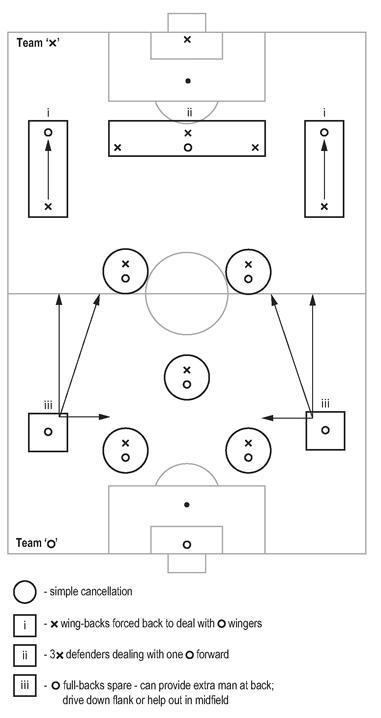

Nelsinho Baptista, the experienced Brazilian coach who took charge of Corinthians in 2007, has developed software to explore the weaknesses of one system when matched against another. ‘Imagine Team A is playing 3-5-2 against Team B with a 4-5-1 that becomes 4-3-3,’ he said. ‘So Team A has to commit the wing-backs to deal with Team B’s wingers. That means Team A is using five men to deal with three forwards. In midfield Team A has three central midfielders against three, so the usual advantage of 3-5-2 against 4-4-2 is lost. Then at the front it is two forwards against four defenders, but the spare defenders are full-backs. One can push into midfield to create an extra man there, while still leaving three v two at the back. So Team B can dominate possession, and also has greater width.’

One of Team A’s central defenders could, of course, himself step up into midfield, but the problem then is that Team A has four central midfielders, and still lacks width. And anyway, if a defender is going to step into midfield, why not simply play a defensive midfielder in that role anyway?

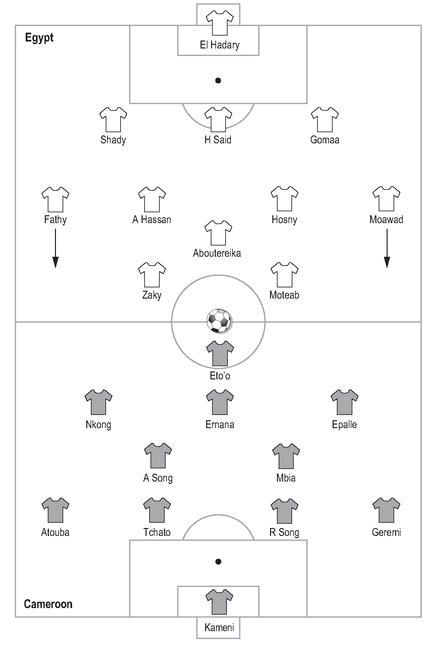

Egypt won the African Cup of Nations with a 3-4-1-2 in both 2006 and 2008, but that was probably largely because straight 4-4-2 still tends to dominate the thinking in Africa. In fact, aside from Egypt - and at times Cameroon - only Guinea and Morocco, both of whom used a 4-2-3-1, did not set up in some form of 4-4-2. Significantly, the majority of the genuine contenders had strong spines and deficiencies wide and, in a generally excellent tournament, the one consistent disappointment was the standard of crossing. That could be a generational freak, or it could be related to the fact that when European clubs are looking to sign African talent, they tend to have what Manchester United’s Africa scout Tom Vernon calls ‘the Papa Bouba Diop template’ in mind. The African players who have succeeded in Europe in the past have usually been big and robust, and so clubs look only for something similar. Players called up by European clubs at a young age develop faster and have a higher profile, and so it is they who make it into the national team.

Decline of 3-5-2

Egypt 4 Cameroon 2, African Cup of Nations group, Baba Yara Stadium, Kumasi, 22 January 2008

Egypt 1 Cameroon 0, African Cup of Nations final, Ohene Djan Stadium, Accra, 10 February 2008

Vernon, who runs an academy in the hills above Accra, also believes the way the game is first experienced by children - at least in Ghana - has a tendency to shape them as central midfielders. ‘Look at how kids play,’ he said. ‘They have a pitch maybe twenty or thirty yards long, and set up two stones a couple of feet apart at either end, often with gutters or ditches marking the boundaries at the sides. So it’s a tiny area. The game becomes all about receiving the ball, turning and driving through the middle.’ The result is that most West African teams - and this was particularly true of Côte d’Ivoire - have at least two good central strikers, so tend to play them, with little width that could have unsettled Egypt’s two excellent wing-backs, Ahmed Fathy and Sayed Moewad.