Invisible Inkling

Authors: Emily Jenkins

INVISIBLE

INKLING

EMILY JENKINS

ILLUSTRATIONS BY

HARRY BLISS

For IvyâE.J.

For SofiâH.B.

Contents

Â

Â

Â

H

i, you.

When you're done reading this, can I ask you a favor?

Please don't tell my parents about Inkling.

And don't tell my sister Nadia, either.

Or Sasha Chin from downstairs.

Actually, please don't tell anyone that I've had an

invisible bandapat living in my laundry basket for six weeks, eating my family's breakfast cereal and playing with my pop-up-book collection.

Inkling needs to stay hush-hush.

For serious.

The only reason I am telling you right now is that if I don't tell somebody, I really think my brain might explode.

And that would not be pretty.

From

Hank Wolowitz

A

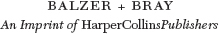

thing about me is, I have an overbusy imagination. Everyone says so.

And it's true. I'm not saying I don't.

I imagine airplanes that argue with their pilots, drinks that change the color of your skin, and aliens who study human beings in science labsâall when I'm supposed to be doing something else.

Like cleaning my room.

Or listening.

But here's a thing about the invisible bandapat who's been living in my laundry basket. He is

not

imaginary.

Inkling is as real as you, or me. Or the Great Wall of China.

I know that's hard to believe. I could hardly believe it myself when I first met him.

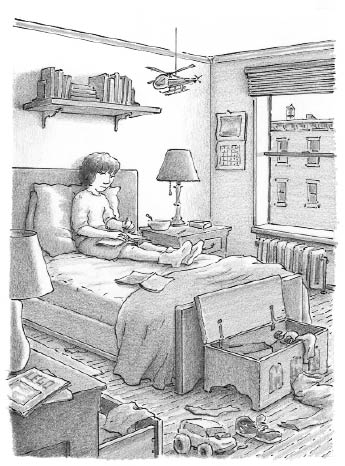

My family is the Wolowitz family. We own an ice-cream shop a couple doors down from our apartment in Brooklyn, New York. The shop is called Big Round Pumpkin: Ice Cream for a Happy World.

The end of the summer before fourth grade, I'm hanging around the shop watching Mom, Dad, and Nadia set up for the day. That's when I first notice the bandapat.

Mom is sweeping the stoop. Nadia is kneeling on the counter in a spangly purple skirt and enormous black boots, writing on the chalkboard. Dad has just finished churning a batch of his new fall flavor, white cherry white chocolate. He's been making samples for a couple weeks, and now he's got it good enough to sell to customers. That's why Nadia is changing the flavor list that hangs over the counter.

A thing about my sister Nadia is, she has pretty handwriting.

A thing about me is, I have invented a lot of new ice-cream flavors.

Pepsi raisin chip.

Cotton-candy Gummi worm.

Poppy seed and waffle.

Sweet-potato pecan.

Don't tell me what you think. I already know most people don't like them.

My

own family

doesn't like them.

Dad makes all the ice cream himself. He invented white cherry white chocolate, nectarine swirl, and Heath bar brownie. Mom invented chocolate-covered pretzel. Nadia made up cinnamon mocha and espresso double shot.

I have invented

eight hundred

different flavorsâbut not a single one has ever gone up on that chalkboard.

Marshmallow peep.

Caramel popcorn.

Dried pineapple.

Cheddar-bunny crunch.

It

is

true that after saying no to every other flavor I invented, Dad whipped up an experiment batch of Cheddar-Bunny crunch earlier this summer. I told him how every kid in Brooklyn eats these Cheddar-Bunny crackers for snack. Other salty things are good in ice creamâpeanuts, pistachios or pretzel bits. Why not Cheddar Bunnies?

Chin from downstairs, my best friend Wainscotting, and Iâwe all three spent the rest of the afternoon barfing.

That's why not Cheddar Bunnies.

Mom said could Dad please not waste time and resources making my weird ice-cream ideas any more. And he said okay.

After that, I stopped trying to help out in the shop so much. My sister works behind the counter on the weekends and in summer when it's busy, but I'm too young, and no other job is as fun as inventing ice-cream flavors.

Anyway, I first notice Inkling that day at the end of the summer in Big Round Pumpkin. There's nothing for me to do while everyone is setting up because two days ago, Wainscotting moved away to Iowa City.

Forever.

Against his will.

I don't know how I'm going to face fourth grade without him. We have been in the same class together since pre-K.

But I don't want to talk about Wainscotting. It makes my throat close up.

I want to tell you about Inkling.

It's hot that day. Sweaty, smelly, New York City Labor Day weekend hot. I open the freezer and lean my face into the cold. “Hank, please,” says Mom as she puts fresh bags in the recycling bins.

I close the freezer and just lean against it.

Then I go into the kitchen and lie down on the cool tiles near the big sink.

“You're underfoot, little dude,” says Dad as he makes his way from the fridge to the front of the store. He's got a large tub of ice cream under each arm.

I know I am underfoot.

But I am so, so bored.

I don't know what to

do

.

I roll over onto my stomach and press my cheek against the floor.

Oh.

There is a Lego propeller underneath the sink.

My Lego propeller that I have been looking and looking for. My City Rescue Copter can't be complete without it.

I reach for itâand my hand touches fur.

Fur.

It is so weird a feeling that I snatch my hand back.

Look around. Squint at the darkness under the sink.

Nothing furry there. Just the pipes and a bucket with a sponge in it.

I put my hand back.

Fur.

Definitely fur. Silky soft. Likeâlike the tail of a fluffy Persian cat.

“Ahhhhhh!” I jerk back and stand up. There is fur that I can't even see! What is happening?

I stumble as I stand and knock over a stack of

metal bowls on the counter.

Bam! Caddacaddacadda

âthey crash around me with a clatter. Pumpkin-colored sprinkles cascade down my legs and skid out across the floor. “Ahhhhhh!”

Dad comes rushing in. “Hank, you okay?”

“There was fur under the sink!” I yell. “I knocked the sprinkles over!”

I am feeling a little insane right now. That was so, so strange, feeling fur that wasn't there.

“What fur?” Dad asks.

“Fur! Under the sink. I felt it but I couldn't see it.”

Dad looks at me. Then looks under the sink. “Little dude, I'm not seeing any fur.”

“Invisible fur!”

“I cleaned under there this morning.”

“But thereâ”

“And even if there

was

invisible fur,” Dad continues, “that's no reason to make so much noise about it.”

“You don't believe me!” I cry.

Dad sighs. “I believe you. It's justâcan you please keep your voice down? The shop is open now. We've got customers out there.”

I stand there, stupidly. The metal bowls surround me on the floor. Sprinkles are everywhere.

Of course Dad doesn't believe me.

It sounds crazy, what I'm saying.

It sounds like a goofy thing a bored kid with an overbusy imagination would invent, just to get attention.

“Sorry,” I say. “I must have imagined it.”

Dad almost never loses his temper. “That's okay, Hank,” he says, scratching his scraggle beard. “Just clean up the sprinkles.”

He hands me the broom, but I don't use it right away. I sit down on the floor and stare at the underneath of the sink.

Either something was there, or it wasn't.

If something

was

there and I can't see it, then I need to get my eyes checked. Last year my teacher read us this book where a girl went blind on a prairie. Ever since then, I've thought it could happen to me. I could go blind, and then I'd have to work on my Lego airport purely by sense of touch and go to school with a Seeing Eye dog.

I don't know what makes a person go blind, actually. But maybe it is something like eating too much cookie-dough ice cream. In that case, I am in serious danger.

On the other hand, if nothing

was

there under the sink and yet I

felt

something, then maybe I have some nerve disease that makes my hands feel fur when really it's only tile. Bit by bit

everything

will feel furry to me. I won't be able to tell the difference between a china cup and a banana. They will both just feel like medium-size piles of fur. I will be the only person ever to have this kind of nerve problem. I'll have to drop out of school so scientists can do tests on me. I'll never learn to type or play the piano.

“Hank!” Dad is back in the kitchen, fetching a carton of milk. I can hear the espresso machine whirring outside. “I asked you to clean up the sprinkles. We can't have the kitchen floor like this. One of us could fall.”

I forgot about the sprinkles. Like, I

couldn't even see them

while I was thinking about the fur. That's how my brain works.

Overbusy.

I get the dustpan. Clean up the sprinkles. Make sure every last one is gone from the kitchen floor.

Then I feel around under the sink. Nothing.

Nothing.

Pipe, tile. Bucket, sponge.

No fur.

But I am thinking: That fur was there.

I mean, I am almost sure it was really there.

It didn't

feel

like my imagination. It felt real.