Invisible Inkling (5 page)

Authors: Emily Jenkins

The Squash Situation

Becomes Desperate

I

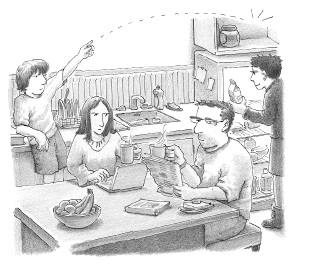

nkling and I settle into a happy routine. At least, it makes me happy. We get up early and watch science videos while eating breakfast cereal. He leans against my leg while we watch, telling me wild stories about bandapat life in Ethiopia, or the Woods of Mystery, or wherever he's supposed to be from.

Sure, he's a liar, but at least he's never boring.

When the rest of my family wakes up, Inkling climbs onto a high shelf in the kitchen and watches us as we eat and talk and get ready for the day. Every now and then I toss him up an Oatie Puff and he eats it in midair. In the afternoons we play Monopoly or Blokus in my room, and I tell him everything that's going on.

Even more than I used to tell Wainscotting.

“I can probably figure out a new plan to defeat Gillicut,” says Inkling, the day after the hair fluff. “But the thing is, I need some squash. I haven't had any for ages and ages.”

“I know,” I tell him. “I'll get you some.”

But finding squash is not so easy. Like I said, no one in my family eats it. My allowance is two dollars a week, but all of that goes to paying Mom back for my Lego airport, which cost a lot. I never see any cash, and Nadia won't pay me for helping with the dog walking.

“I need the squash, Wolowitz,” Inkling says. “I'm in a weakened state. My bandapat instincts are dulled. You saw how the rootbeer nearly ate me. And your dad sat on me, too.”

I nod.

“Get me squash,” he says. “Get me squash or I can't stay here anymore.” Then, coaxing: “Get me squash and I can solve your Gillicut problem.”

“When do you need it by?” I ask.

“Yesterday!” cries Inkling. “But today will do.”

So we try. He climbs onto my back, and we go downstairs to Chin's apartment. “Hello,” I say, when Chin opens the door. “Do you have any squash I can borrow?”

Chin laughs. She is wearing a tutu. I have never seen her dressed that way before. “I don't think so,” she answers. “Mom, do we have squash?”

Chin's mom comes up. “No squash. Tell your dad I'm sorry, Hank.”

“It's not for my dad.”

“Then what's it for?” Chin wants to know.

Locke and Linderman appear at the door. They are wearing tutus also.

Suddenly I can't think of a reasonable answer.

“I didn't know you had friends over,” I say to Chin. “I'll see you later.”

“Do you want to come in?” she asks. “We're doing a ballet and we could totally use a prince.”

“That's okay.”

“There could be a sword fight if you want. It doesn't have to be leaping around or romance or anything.”

“No, no,” I say. “Hello, Dahlia. Hello, Emma. I have to look for squash now.”

I turn and run up the stairs.

“Keep trying,” says Inkling.

“But that was a disaster,” I say.

“Keep trying,” he repeats. “I need the squash.”

We knock at Seth Mnookin's, but only Rootbeer is home. She barks like a crazy dog when she smells Inkling on the other side of the door.

“Nadia?” I ask my sister, back in the apartment. “Will you buy me a squash? It'll only cost maybe four dollars, and I'll pay you back when I'm done paying Mom for the Lego airport.”

“Nuh-uh,” says Nadia, not even looking up from her book. “You're gonna be owing on that airport for, like, two years.”

“Come on,” I beg. “Just one little squash.”

“No way,” says Nadia. “You never paid me back when I bought you those waffle cookies. Or when I fronted you money for the helicopter pop-up book.”

She's right.

“I'm sorry,” I tell Inkling, when we're alone in my room again.

“But I need it,” he says. “Need my squash, so bad.”

“No one has it,” I say. “And I don't have any money.”

“I'm sluggish,” he moans. “I'm losing fur in patches. You've gotta help me, Wolowitz. Otherwise how can

I

help you?”

I can hear the desperation in his voice.

I want to help. I really do.

The question is, how?

I Am Not an Ambassador

of Goodwill

N

o squash, no solution from Inkling. Over the next week, Gillicut gets not only five Tupperwares of rainbow sprinklesâone each dayâbut a nectarine, two bags of sandwich cookies, a bag of Cheddar Bunnies, a yogurt drink, pretzels, raspberries, a Luna bar, and a box of dried cranberries.

The Monday after, Chin convinces me I should I talk to the lunch aides.

“Don't tattle,” says the old, blind lady. “You boys work it out.”

“Tell him not to,” says the bored lady in the sunglasses.

“Tell him I'm writing his name down,” says the cranky lady with the orange hair.

But writing his name down doesn't help. Gillicut is on a rampage. And he's not dumb: He kicks under the table, pinches while he's smiling, and never makes a move until the aides are busy with someone else.

Tuesday, I talk to my dad about the problem, when he's reading to me before bed.

“There must be a peaceable solution to this conflict, little dude,” he says. “Can you think of a peaceable solution?”

I shake my head.

Dad sighs. He's a pacifist, which means he doesn't believe in war, karate lessons, or toy guns. “Did you try saying âPlease leave me alone'?” he asks.

“Yes.”

“Did you try saying âBack off'?”

“Yes.”

“But the guy didn't back off?”

“No.”

“Oh, little dude,” my dad says. “That's rough.”

“I know,” I say. He takes my hand and squeezes.

“Let me think on it,” he says.

Wednesday, I talk to Ms. Cherry. I tell her how Gillicut goes on the rampage.

She says, “I'll mention it to the lunch aides.”

I tell her they already know.

She says, “I'll talk to his teacher”âMr. Hwang down the hall. And, “Let me know if it happens again, 'kay?”

Okay.

And then it does happen again. And again.

Friday, I go to see Ms. Cherry during recess when she has more time to listen. I explain how Gillicut's a bully and a dirtbug and a caveperson.

Ms. Cherry is sitting at her desk, eating a wrap sandwich. A bit of mayo blobs on her upper lip. I think that's why teachers don't like to eat in front of us kids. In case they look silly.

“Mr. Hwang already talked to Bruno and to Bruno's dad,” says Ms. Cherry. “He said absolutely: no more kicking and no more taking lunch items from other kids. Bruno agreed.”

“But he took my lunch

today

!” I protest.

“He did?”

“Yes!”

“Well, I'll tell Mr. Hwang. But let me share something with you, Hank.” Ms. Cherry pats her complicated hair.

“What?”

“Mr. Hwang thinks Bruno could use some friends. Since the summer, his parents don't live together anymore. He's just with his dad, and he's been going through a rough time. He needs everyone to be nice to him.”

No.

“Maybe if you offer to share your sprinkles, he'll offer to share something back. You could reach out!”

No, no.

“You can switch the situation around. You can be an ambassador of goodwill.”

No, no,

no

.

“Remember, Hank,” says Ms. Cherry. “Strangers are friends waiting to happen. We don't use words like

bully

and

dirtbug

and

caveperson

to talk about our friends, now, do we?”

And then, answering herself: “No. We don't. If you are using words like that with Bruno, the way you just did talking to meâwell, then you're giving

him

a hard time, aren't you?”

“How did it go with Ms. Cherry?” Inkling asks later as we move our pieces around the Monopoly board. He's eating kidney beans with whipped cream on top, his new favorite dinner.

“Bleh,” I say.

“What happened?”

I am too tired to tell the whole story. “Ms. Cherry understands Everyday Math,” I tell Inkling. “But she does not understand people.”

“I don't understand people, either,” says Inkling, collecting the money on Free Parking. “Not liking squash, wanting to be alone in the bathroom, all that stuff is incomprehensible.”

You understand us when it matters,

I think.

But that's too mushy to say out loud.

Instead, I buy Park Place and build four houses.

Terror in the Aisles

of Health Goddess

O

n the weekend, Mom goes to Health Goddess, the natural-food store near our home. It's run by friends of my parents.

“Come on,” I tell Inkling. “I'm gonna get you a squash now.” He climbs onto my back, warm and heavy, and we go with Mom. I stroll through aisles of bean soup, almond butter, and other foods I don't like until we get to the produce section.

As we round the corner, Inkling's legs kick with excitement. He breathes hard in my ear.

And then I see it, too.

Squash! Piles and piles of squash! Tan ones, green ones, yellow. Even striped.

I read the signs: butternut, acorn squash, banana squash, and delicata.

“Mom!” I call. She is looking over the apples, selecting ones without bruises. “Can we get some squash?”

She crinkles her nose at me. “Hmm. What do you need it for?”

“Just to eat,” I say, innocently. “I feel like squash. You know, um, for dinner.”

“Hank, you know you don't like squash. When we had it at Aunt Sophia's, you made gagging noises.”

“Tastes change. Maybe I like it now.”

“That was only two months ago.”

“Maybe I like it cooked a different way!”

“It was baked with brown sugar and butter.”

Inkling whispers in my ear. “Bandapats eat it raw.”

“You don't have to cook it,” I tell Mom.

“You can't eat raw squash,” she says. “Nobody eats raw squash, except maybe zucchini. Is that what you want, Hank? Zucchini?”

Inkling speaks fiercely in my ear: “No! No zucchini!”

“No!” I tell Mom. “I wantâ”

“Butternut,” Inkling whispers.

“Butternut!”

Mom narrows her eyes at me. “You want to eat raw butternut squash for dinner.”

“Yes!” I cry. “Please?”

“No.” She selects a bunch of apples and puts them in a bag. “That's ridiculous, Hank. It's not even edible raw. I know you won't like it, and I don't want to waste money. Let's buy broccoli.” She turns decisively and walks to the other end of the produce section, where she begins filling bags with green vegetables.

Inkling is panting on my back, muttering: “Squash here, squash there, squash piled high. But squash for Inkling? No squash for Inkling.”

“Calm down,” I say, under my breath. “I'll come shopping another day with Dad. Maybe I can get

him

to buy some.”

“Want the squash. Need it now. Squash! Squash!”

“Keep your voice down!” I hiss.

Inkling begins muttering againâmore to himself than to me. “Butternut. Acorn. Butternut. Acorn . . . Butternut!”

Suddenly, Inkling is not on my back anymore.

Where is he?

Oh.

Oh no.

There is a butternut squash with two bites out of it scootching down the aisle of Health Goddess.

As if it hopes no one will notice it.

Mom runs over from the broccoli and grabs my arm. “Hank, don't freak out,” she says, “but I think there's a rat in here. See that squash moving across the floor?”

“Oh, I'm sure it's not a rat,” I say, but I can't think of another reason the squash would be moving.

“Well, if it's not a rat, it's some other vermin. We can't have that here in Health Goddess.” She runs to a corner of the market and grabs a broom. “Shoo!” she cries, chasing the squash.

Whack!

She hits it hard, once.

The squash stops moving.

The squash wiggles, feebly, as if injured. Is Inkling okay?

Whack!

Mom hits it again.

“Mom, stop!”

Erik, the guy who owns Health Goddess, runs over to see what's up. “There's a rat under that squash,” Mom tells him. “You can't see it, but it's there. Get another broom!”

Several customers are gathering round. Two are shrieking and standing on wooden produce boxes. One dad has scooped up his three-year-old, clutching the kid like there's a lion loose in the market.

The squash is trying to move across the floor again, heading toward the door.

Whack!

Mom hits it again.

“Stop!” I cry.

And

slam!

Erik comes back with a mop and hits it from the other side. “Did you see it?” he yells. “I can't see it!”

Whack!

Mom again.

“Don't hurt him!” I yell. But no one is listening to me. People are shrieking “Rat! Rat!” and “Get it out of here!” and things like that.

Slam!

Erik lands a good one on the top of the butternut. Half of it breaks off.

Then the other half begins limping down the aisleâif squash can limpâand Mom runs after it. “Shoo! Out you go!”

I run after her and try to grab her arm, but she's fast, and she hits it again with her broom.

Whack!

The half squash shatters into many, many pieces.

Mom looks down. No rat in sight. “Did it run outside? Hank, did you see it?”

I ignore her and drop to my knees, feeling around on the floor for Inkling.

He must be hurt. He might even be bleeding or have a broken bone.

“Maybe it was just a baby rat. Maybe it was a lost chipmunk,” Mom is saying.

I touch the floor, the shelves, the corners, feeling around like a blind person.

“Hank, what are you doing?”

“Cleaning up the squash,” I say, pushing some blobs of butternut around on the floor.

“Oh.” Her face breaks into a smile. “That's nice. Since when are you such a helpful kid?”

She turns and begins talking to Erik about how the baby rat or chipmunk is probably still somewhere in the market, and it's really fast. That's why neither of them got a good look at it. They need to put out no-kill peanut-butter traps.

I go back to running my hands along the floors, searching for Inkling. He must be wounded, or he'd come to me. And he must be scared to make any noise, because now Erik's on the lookout for a rat.

My hand finally hits quivering fur and I can feel Inkling, shaking and limp, squeezed between two bins of granola. I'm so relieved I want to cry, but instead I pick him up. He crawls slowly onto my back, moving as if he's bruised all over.

Keeping him gently in place with one hand, I pick up the unshattered half of the butternut squash that's lying in the produce section. “Excuse me, Erik?” I say, interrupting his chat with Mom. “Since you probably can't sell this, would it be okay if I took it home?”

He tells me yes, and Inkling and I head outside and wait on a bench for Mom to finish her shopping.

“Yummy, yummy squashy goodness,” Inkling mumbles to himself, as the butternut disappears in small, eager bites. He makes grunting noises as he eats.

In minutes, the whole thing is gone. Inkling burps in satisfaction.

When she comes outside, Mom asks me what happened to that squash I asked Erik for.

“I took a bite and you were right,” I tell her. “I don't like it after all. I threw it in the trash. I don't know what I was thinking.”

“I knew you wouldn't like it.” She laughs. “I guess you learned a lesson, huh?”

“Yeah,” I lie. “I did.”