Iran: Empire of the Mind (5 page)

Some have explained the inconsistency by suggesting that different classes of Iranian society followed different beliefs; effectively different

religions. As we have seen, there probably was some considerable plurality of belief within the broad flow of Mazdaism at this time. But it seems more likely that the plurality was socially vertical rather than horizon-tal—in other words, a question of geography and tribe rather than social class. Perhaps an earlier, pre-Zoroastrian tradition of burial still lingered and the elevated position of all the royal tombs was a kind of compromise. Half-way between heaven and earth: itself a strong metaphor. Around the tomb of Cyrus lay a paradise; a garden watered by irrigation channels (our word paradise comes, via Greek, from the Old Persian

paradaida

, meaning a walled garden). Magian priests watched over the tomb and sacrificed a horse to Cyrus’ memory each month.

14

Cyrus had been a conqueror, but a conqueror with an imaginative vision. He was at least as remarkable a man as the other conqueror, Alexander, whose career marks the end of the Achaemenid period, as that of Cyrus marks the beginning. Maybe as a youth Cyrus had a Mazdaean tutor as remarkable as Aristotle, who taught Alexander.

Religious Revolt

Cyrus was succeeded by his son Cambyses (Kambojiya), who extended the empire by conquering Egypt, but in a short time gained a reputation for harshness. He died unexpectedly in 522

BCE

, according to one source by suicide, after he had been given news of a revolt in the Persian heartlands of the empire.

An account of what happened next appears on an extraordinary rock relief carving at Bisitun, in western Iran, about twenty miles from Kermanshah, above the main road to Hamadan. According to the text of the carving (executed in Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian) the revolt was led by a Magian priest, Gaumata, who claimed falsely to be Cambyses’s younger brother, Bardiya. Herodotus gives a similar version, saying that Cambyses had murdered the true Bardiya some years earlier. The revolt led by Gaumata seems to have drawn force from social and fiscal grievances, because one of his measures to gain popularity was to order a three-year remission of taxes—another to end military conscription.

15

Pressure had built up over the decades of costly foreign wars under Cyrus and Cambyses. But

Gaumata also showed strong religious enthusiasm or intolerance, because he destroyed the temples of sects he did not approve of.

An Iranian revolution, led by a charismatic cleric, seizing power from an oppressive monarch, asserting religious orthodoxy, attacking false believers, and drawing support from economic grievances—in the sixth century

BCE

. How modern that sounds. But within a few months, Gaumata was dead, killed by Darius (Daryavaush) and a small group of Persian confederates (a killing that sounds more like an assassination than anything else). The carving at Bisitun was made at Darius’s orders, and it presents his version of events, as put together after he had made himself king and the revolt had finally been put down. The carving itself says that copies of the same text were made and distributed throughout the empire. And what a revolt it had been—Babylon revolted twice, and Darius declared that he fought nineteen battles in a single year. It was really a series of revolts, affecting all but a few of the eastern provinces of the empire. The Bisitun carving illustrates this by showing a row of defeated captives, each representing a different people or territory. Whatever the true nature of the rebellion and its origins, it was no simple palace coup, affecting only a few members of the elite. It was just the first of several religious revolutions, or attempted revolutions, in Iran’s history, and it was no pushover.

Bisitun was chosen for Darius’s grand rock-carving because it was a high place, perhaps already associated with the sacred, close by where he and his companions had killed Bardiya/Gaumata. The site at Bisitun is a museum of Iranian history in itself. Aside from the Darius rock relief, there are caves that were used by Neanderthals 40,000 years ago or more, and by others generations later. Among other relics and monuments, there is a rock carving of a reclining Hercules from the Seleucid period, a Parthian carving depicting fire worship, a Sassanian bridge, some remains of a building from the Mongol period, a seventeenth-century

caravanserai

, and not far away, some fortifications apparently dating from the time of Nader Shah in the eighteenth century.

Many historians have been suspicious about the story of the false Bardiya. The Bisitun carving is a contemporary source, but it is plainly

a self-serving account to justify Darius’s accession. It is confirmed by Herodotus and other Greek writers, but they all wrote later and would naturally have accepted the official version of events, if other dissenting accounts had been stamped out. Darius was not a natural successor to the throne. He was descended from a junior branch of the Achaemenid royal family, and even in that line he was not pre-eminent—his father was still living. Could a Magian priest have successfully impersonated a royal prince some three or four years after the real man’s death? Is it not rather suspect that Darius also discredited other opponents by alleging that they were impostors?

If the story was a fabrication, Darius was certainly brazen in the presentation of his case. In the Bisitun inscriptions, the rebel leaders are called ‘liar kings’, and Darius declares, appealing to religious feeling and Mazdaean beliefs about

arta

and

druj

:

[…]

you, whosoever shall be king hereafter, be on your guard very much against Falsehood. The man who shall be a follower of Falsehood—punish him severely

[…]

and:

[…] Ahura Mazda brought me aid and the other gods who are, because I was not disloyal, I was no follower of Falsehood, I was no evil-doer, neither I nor my family, I acted according to righteousness, neither to the powerless nor to the powerful, did I do wrong…

and again:

This is what I have done, by the grace of Ahura Mazda have I always acted. Whosoever shall read this inscription hereafter, let that which I have done be believed. You must not hold it to be lies.

Perhaps Darius protested a little too much. Another inscription in Darius’s words, from another site, reads:

By the favour of Ahura Mazda I am of such a sort that I am a friend to right, I am not a friend to wrong. It is not my desire that the weak man should have wrong done to him by the mighty; nor is it my desire that the mighty man should have wrong done to him by the weak. What is right, that is my desire. I am not a friend to the man who is a lie-follower […] As a horseman I am a good horseman. As a bowman I am a good bowman both afoot and on horseback…

16

The latter part of this text, though telescoped here from the original, echoes the famous formula from Herodotus and other Greek writers, that Persian youths were brought up to ride a horse, to shoot a bow, and to tell the truth. Darius was pressing every button to stimulate the approval of his subjects. Even if one doubts the story of Darius’s accession, the evidence from Bisitun and his other inscriptions of his self-justification and the use of religion by both sides in the intensive fighting that followed the death of Cambyses nonetheless stands. It is a powerful testimony to the force of the Mazdaean religion at this time. Even the suppressors of the religious revolution had to justify their actions in religious terms. Although Darius by the end reigned supreme, the inscriptions give a strong sense that he himself was nonetheless subject to a powerful structure of ideas about justice, truth and lies, right and wrong, that was distinctively Iranian, and Mazdaean.

The Empire Refounded

Darius’s efforts to justify and dignify his rule did not end there. He built an enormous palace in his Persian homeland, at what the Greeks later called Persepolis (‘city of the Persians’)—thus starting afresh, away from the previous capital of Cyrus at Pasargadae. Persepolis is so big that a modern visitor walking over the site, wandering bemused between the sections of fallen columns and the massive double-headed column capitals that crashed to the ground when the palace burned, may find it difficult to orientate himself and make sense of it. The magnificence of the palace served as a further prop to the majesty of Darius, and the legitimacy of his rule; but helped in turn to create a lasting tradition, a mystique of magnificent kingship that might not have come about but for the initial doubts over his accession. A dedicatory inscription at Persepolis played again on the old theme:

May Ahura Mazda protect this land from hostile armies, from famine, and from the Lie.

The motif of tribute and submission is also repeated from Bisitun: row upon row of figures representing subjects from all over the empire

are shown queuing up to present themselves, frozen forever in stone relief. The purpose of the huge palace complex at Persepolis is not entirely clear. It may be that it was intended as a place for celebrations and ceremonial at the spring equinox, the Persian New Year (

Noruz

—celebrated on and after 21 March each year today as then). The rows of tribute-bearers depicted in the sculpture suggest that it may have been the place for annual demonstrations of homage and loyalty from the provinces. Whatever the grandeur of Persepolis, it was not the main, permanent capital of the empire. That was at Susa, the old capital of Elam. This again shows the syncretism of the Persian regime. Cyrus had been closely connected with the royal family of the Medes, and the Medes had a privileged position, with the Persians, as partners at the head of the Empire. But Elam too was important and central: its capital, its language, in administration and monumental inscriptions. This was an empire that always, for preference, flowed around and absorbed powerful rivals: its first instinct, unlike other imperial powers, was not to confront, batter into defeat, and force submission. The guiding principles of Cyrus persisted under Darius and at least some later Achaemenid rulers.

Fig. 2. Darius I presides over his palace at Persepolis—a massive demonstration of imperial confidence, arising perhaps out of an uneasy conscience.

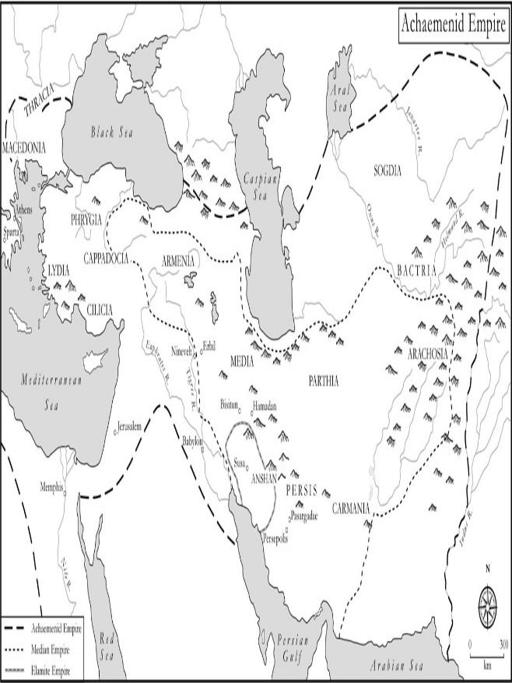

Darius’s reign saw the Achaemenid empire in effect re-founded. It could have gone under altogether in the rebellions that followed the death

of Cambyses. Darius maintained Cyrus’s tradition of tolerance, permitting a plurality of gods to be worshipped as before; and maintained also the related principle of devolved government. The provinces were ruled by satraps, governors who returned a tribute to the centre but ruled as viceroys (two other officials looked after military matters and fiscal administration in each province, to avoid too much power being concentrated in any one pair of hands). The satraps often inherited office from predecessors within the same family, and ruled their provinces according to pre-existing laws, customs and traditions. They were, in effect, provincial kings; Darius was a King of Kings (

Shahanshah

in modern Persian). The empire did not attempt as a matter of policy to Persianise as the Roman empire, for example, later sought to Romanise.

The certainties of religion, the principle of sublime justice they underpinned, and the magnificent prestige of kingship were the bonds that held together this otherwise diffuse constellation of peoples, languages and cultures. A complex empire, accepted as such, and a controlling principle. The system established by Darius worked, proved resilient, and endured.

Tablets discovered in excavations at Persepolis show the complexity and administrative sophistication of the system Darius established. Although some payments were made in silver and Darius established a standard gold coinage, much of the system operated by payments in kind; assessed, allocated and receipted for from the centre. State officials and servants were paid in fixed quantities of wine, grain or animals; but even members of the royal family received payments in the same way. Officials in Persepolis gave orders for the levying of taxes in kind in other locations, and then gave orders for payments in kind to be made from the proceeds, in the same locations. Messengers and couriers were given tablets to produce at post-stations along the royal highways, so that they could get food and lodging for themselves and their animals. These tablets recording payments in kind cover only a relatively limited period, from 509 to 494

BCE

. But there are several thousand of them, and it has been estimated that they cover supplies to more than 15,000 different people in more than 100 different places.

17