Iran: Empire of the Mind (35 page)

Pushing forward despite these storms, the government appointed a young American, Morgan Schuster, as financial adviser. Schuster presented clearsighted, wide-ranging proposals that addressed law and order and the government’s control of the provinces as well as more narrowly financial matters; and began to put them into effect. Fulfilling Iranian aspirations, or at least the aspirations of some Iranians, in ways that British realpolitik had disappointed them, the United States in this phase and later looked like the partner Iran had long hoped to find in the West; anti-feudal, anti-colonial; modern, but not imperialist; a truly benevolent foreign power that would, for once, treat Iran with respect, as an agent in her own right, not as an instrument. People have suggested that there are only a limited number of stories in literature and folklore; that all the great variety ever told can be reduced to just a handful of archetypal plots. If that is so, and if we think of the British and the Russians in the nineteenth century as the Ugly Sisters, then at this time Morgan Schuster and by extension the United States, looked like Prince Charming. But the story was not to have a happy ending.

The Russians objected to Schuster’s appointment of a British officer to head up a new gendarmerie (for tax collection), on the basis that it should not have been made within their sphere of influence without their consent, and the British acquiesced with their uglier sister. Schuster assessed, probably correctly, that the deeper Russian motive was to keep the Persian government’s affairs in a state of financial bankruptcy, and thus in a position of relative weakness (in the position of supplicant for Russian loans), the better to manipulate them. Any determined effort to

put the government of Persia on a sound financial footing, as Schuster’s reforms threatened to do, was a threat to Russian interests. The Russians presented an ultimatum: Schuster had to go. A body of women surged into the Majles to demand that the ultimatum be rejected, and the Majles agreed with them, insisting that the American should stay. But the Russians sent troops to Tehran and as they drew near, the Bakhtiaris and conservatives in the cabinet enacted what has been called a coup, and dismissed both Schuster and the Majles in December 1911.

24

Schuster later wrote a book about his time in Iran called

The Strangling of Persia

, in which (despite what today reads sometimes with a rather prosy, evangelical style) he expressed his admiration for the moral courage and determination of the people he worked with in the period of the Constitutional Revolution. The book explains much about the revolution, and about Persia at the time, but also about Schuster’s attitudes to the country, and also perhaps something of the reasons why he and by extension the US were so highly regarded by Iranians. He wrote of the Majles that it:

… more truly represented the best aspirations of the Persians than any other body that had ever existed in that country. It was as representative as it could be under the difficult circumstances which surround the institution of the Constitutional Government. It was loyally supported by the great mass of the Persians, and that alone was sufficient justification for its existence. The Russian and British Governments, however, were constantly instructing their Ministers at Teheran to obtain this concession or to block that one, failing utterly to recognise that the days had passed in which the affairs, lives and interests of twelve millions of people were entirely in the hands of an easily intimidated and willingly bribed despot.

25

It would be incorrect to put all the blame for the outcome of the Constitutional revolution onto the foreigners. The revolution had brought forward violence and rancour between the groups represented in the Majles, and the divisions contributed to the events of December 1911. One could speculate (not least on the basis of the use of terror by other revolutionaries in other revolutions) that if the revolution had not been cut off at that point the violence might well have got a great deal worse, possibly with very damaging long-term effects. But that is to speculate too far. We do not know how it would have turned out. Revolutions may have family resemblances, but they have no timetable and no blueprint, and the

constitutional revolution arose out of distinctive and unique political and social circumstances. There were many positive elements in the situation as it was before December 1911, as well as the negative; above all that at last (as Schuster pointed out) the country had a truly popular government, and that it was addressing as a priority the fundamental problem of the fiscal structures. Revolutionaries and people showed a strong solidarity against external meddling, a powerful enthusiasm for constitutional government, and for their elected Majles. This enthusiasm had been strong enough to overturn one coup already, and was strong enough to sustain the principles of constitutionalism later too, notably in 1919-1920. It gives the lie to those who condescendingly suggest that Iran, or Middle Eastern countries in general, are somehow culturally unsuited to constitutional, representative or (later) democratic government. When those forms of government were offered, Iranians grabbed them with both hands, as other peoples invariably have in other times and places.

Persia, Oil, Battleships and the First World War

Through this period, even before the British legation had been used for sanctuary by the protesters in 1906, new developments had been at work to reshape Britain’s attitude to Iran. Since at least the turn of the century, Britain’s traditional rivalries with France and Russia had been replaced by an awareness of the danger of the growing power and belligerence of Germany. France and Russia allied with each other (by implication, against Germany) in 1894; Britain and France in 1904, and Britain France and Russia all together in 1907 (the Triple Entente). Particularly sharp for Britain was the German programme of naval shipbuilding over this period. Since the battle of Trafalgar in 1805 Britain had maintained an unrivalled dominance of the world’s oceans; an essential support to her world empire. But under Emperor Wilhelm II the Germans began building modern warships at a rapid rate, threatening the Royal Navy’s dominance. British shipyards began to turn out ships to match the German programme. In 1906 the British launched

HMS Dreadnought

, which was said to have rendered all previous warships obsolete at a stroke by its combination of speed and the coordinated firepower of its simplified

armament. In 1912 the British navy switched from coal to oil as fuel: oil burned more efficiently and was less bulky. But whereas Britain had huge domestic reserves of coal, oil had to be sought elsewhere. Oil had been discovered (the first oil to be found in the Middle East) in large quantities under the terms of the D’Arcy concession, near Ahwaz in Khuzestan, in south-west Iran, in 1908.

Persia had for decades been of importance to Britain for the sake of the north-west frontier of India (perhaps of declining importance, especially after the Triple Entente), but now the oil reserves of Khuzestan became vital for the security of the whole British empire. Britain’s sphere of influence according to the agreement with Russia was quickly extended westwards to include the rest of the Persian Gulf coast and the oil fields. The Anglo-Persian Oil Company was formed to exploit the oil, and in 1914 the British government bought up a majority share in it.

Partly because of the oil, but also because Britain’s rivals fell away one by one over the following years, Britain gradually became the dominant external power in Iran in the decade that followed 1911. It was a period of deepening chaos, poverty and suffering. The Russians fired on revolutionaries in several of the cities in their northern zone in the aftermath of the coup of December 1911, notably in Mashhad, where protesters took sanctuary in the shrine of the Emam Reza, only for the Russian artillery to shell the shrine itself, an act of sacrilege and humiliation that was deeply felt throughout the country. The British Embassy reported in 1914 that the central government had little influence on events outside Tehran.

26

The British and the Russians exercised a degree of control in their respective zones, but their grip was far from absolute, as was

shown by the success of the

Jangali

movement in Gilan, under the charismatic leader Kuchek Khan, which continued to sustain some of the spirit of independence that had inspired the revolution (

Jangal

means forest, an allusion to the dense forests of the Caspian coast).

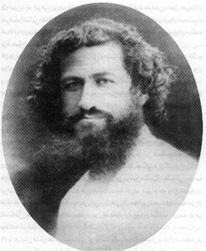

Fig. 14. Kuchek Khan was the leader of the Jangalis of Gilan, who attempted to uphold the principles of the Constitutional Revolution, but later took a leftist direction under Bolshevik influence and were eventually defeated by Reza Khan’s Cossacks.

The revolution is usually said to have ended in 1911, but this date is rather artificial. The constitution established by the revolution was not overturned, and a new Majles convened in December 1914. The spirit of the revolution and the ideals and expectations of the constitutionalists were not crushed. They resurfaced again and again in the events that followed. The revolution was a watershed in the history of Iran, as the episode in which previously more or less inchoate strands of thinking and opinion came together in concrete political form, shifted, changed and acquired permanent significance. It also, with the focus of popular debate in Tehran and the role of regional assemblies in sending delegates to the Majles, had a centralising and unifying effect, strengthening the nationalist sympathies of many of those delegates. The revolts in Gilan (and later Azerbaijan) had national, not separatist aims. There could be no going back to the pre-1906 state of things.

During the First World War, despite the government’s declaration that Persia was neutral, the country was divided up by the different players that maintained troops in different sectors. There were the Russians in the north, but also the Jangalis and in Tehran the troops controlled (at least nominally) by the government—the Cossack brigade and the Swedish gendarmerie. Set against the Russians were the Ottomans, who made an incursion into the country in the west and north, and their allies the Germans. For the most part none of these armed elements was strong enough to control large areas of territory or establish overall supremacy, and most of the fighting was low-intensity and indecisive most of the time. But in the north-west the Ottomans and the Russians fought each other more aggressively, doing much damage to the villages and the local population. For a time a revived rump of the constitutionalist movement was set up under Ottoman and German protection in Kermanshah, and for a period in 1915, when the Ottomans were doing well in the north and the Germans, allied with the Qashqai and others in the south, also made

considerable progress, prospects for them looked good. The British pulled out of their consulates in Hamadan, Isfahan, Yazd and Kerman.

But in the south the British set up a force called the South Persia Rifles in the spring of 1916, primarily to protect the oilfields; they also had a close relationship with the Bakhtiari, some of the Arab tribes of Khuzestan and those of the Khamseh confederation. Despite the skilful guerrilla war masterminded by the brilliant German adventurer Wilhelm Wassmuss (who has been compared to Lawrence of Arabia) the British slowly regained the upper hand, and the situation in Iran turned against the Germans and the Ottomans, as in the wider war, despite the Russians and their troops being removed from the equation after the October revolution of 1917. By the time of the armistice in November 1918 Wassmuss was captured near Isfahan and the British were resurgent in Persia.

By the end of the war the country was in a terrible state. There had been a severe famine in the years 1917-1918, partly a result of the dislocation of trade and agricultural production caused by the war. The effect of the Russian revolution on trade was devastating; before 1914, 65 per cent of foreign trade had been trade with Russia; this fell to 5 per cent by the end of the First World War. The famine was followed by a serious visitation of the global influenza epidemic in 1918-1919, and typhus killed many too. Brigandage was common. Although there were British troops in several parts of the country, many tribal groups were in arms, and the Jangalis were still in control of most of Gilan. Having begun as pro-constitutionalist, the Jangalis came under Russian Bolshevik influence, and in the summer of 1918, with the help of some Bolsheviks, they had forced a British force under General Dunsterville to retreat from a confrontation in Gilan. By this time Dunsterville had learned rather more about the Jangalis since January 1918, before he took up his duties in Persia, when he wrote in his diary:

‘I get a wire to say that Enzeli, my destination on the Caspian Sea has been seized by some horrid fellows called Jangalis (a very suggestive name) who are intensely anti-British and are in the pay of [the] Germans’

27

.