Iron Kingdom : The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947 (5 page)

Read Iron Kingdom : The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947 Online

Authors: Christopher Clark

When they became Electors of Brandenburg, the Franconian Hohenzollerns joined a small elite of German princes – there were only seven in all – with the right to elect the man who would become Holy Roman Emperor of the German Nation. The Electoral title was an asset of enormous significance. It bestowed a symbolic pre-eminence that was given visible expression not only in the sovereign insignia and political rites of the dynasty but also in the elaborate ceremonials that attended all the official functions of the Empire. It placed the sovereigns of Brandenburg in a position periodically to exchange the territory’s Electoral vote for political concessions and gifts from the Emperor. Such opportunities arose not only on the occasion of an actual imperial election, but at all those times when a still reigning emperor sought to secure advance support for his successor.

The Hohenzollerns worked hard to consolidate and expand their patrimony. There were small but significant territorial acquisitions in almost every reign until the mid sixteenth century. Unlike several other

German dynasties in the region, the Hohenzollerns also managed to avoid a partition of their lands. The law of succession known as the

Dispositio Achillea

(1473) secured the hereditary unity of Brandenburg. Joachim I (r. 1499–1535) flouted this law when he ordered that his lands be divided at his death between his two sons, but the younger son died without issue in 1571 and the unity of the Mark was restored. In his political testament of 1596, Elector John George (r. 1571–98) once again proposed to partition the Mark among his sons from various marriages. His successor, Elector Joachim Frederick, succeeded in holding the Brandenburg inheritance together, but only thanks to the extinction of the southern, Franconian line of the family, which allowed him to compensate his younger brothers with lands from outside the Brandenburg patrimony. As these examples suggest, the sixteenth-century Hohenzollerns still thought and behaved as clan chiefs rather than as heads of state. Yet, although the temptation to put the family first continued to be felt after 1596, it was never strong enough to prevail against the integrity of the territory. Other dynastic territories of this era fractured over the generations into ever smaller statelets, but Brandenburg remained intact.

9

The Habsburg Emperor loomed large on the political horizons of the Hohenzollern Electors in Berlin. He was not just a potent European prince, but also the symbolic keystone and guarantor of the Empire itself, whose ancient constitution was the foundation of all sovereignty in German Europe. Respect for his power was intermingled with a deep attachment to the political order he personified. Yet none of this meant that the Habsburg Emperor could control or single-handedly direct affairs within the Empire. There was no imperial central government, no imperial right of taxation and no permanent imperial army or police force. Bending the Empire to his will was always a matter of negotiation, bargaining and manoeuvre. For all its continuities with the medieval past, the Holy Roman Empire was a highly fluid and dynamic system characterized by an unstable balance of power.

In the 1520s and 1530s, the energies released by the German Reformation agitated this complex system, generating a process of galloping polarization. An influential group of territorial princes adopted the Lutheran confession, along with about two-fifths of the imperial Free Cities. The Habsburg Emperor Charles V, determined both to safeguard the Catholic character of the Roman Empire and to consolidate his own imperial dominion, mustered an anti-Lutheran alliance. These forces won some notable victories in the Schmalkaldic War of 1546–7, but the prospect of further Habsburg advancement sufficed to bring together the dynasty’s opponents and rivals within and outside the Empire. By the early 1550s, France, ever anxious to block the machinations of Vienna, had begun to provide military support for the Protestant German territories. The consequence of the resulting stalemate was the compromise settlement agreed at the 1555 Diet of Augsburg. The Peace of Augsburg formally acknowledged the existence of Lutheran territories within the Empire and conceded the right of Lutheran sovereigns to impose confessional conformity upon their own subjects.

Throughout these upheavals, the Hohenzollerns of Brandenburg pursued a policy of neutrality and circumspection. Anxious not to alienate the Emperor, they were slow to commit themselves formally to the Lutheran faith; having done so, they instituted a territorial reformation so cautious and so gradual that it took most of the sixteenth century to accomplish. Elector Joachim I of Brandenburg (1499–1535) wished his sons to remain within the Catholic church, but in 1527 his wife Elizabeth of Denmark took matters into her own hands and converted to Lutheranism before fleeing to Saxony, where she placed herself under the protection of the Lutheran Elector John.

10

The new Elector was still a Catholic when he acceded to the Brandenburg throne as Joachim II (r. 1535–71), but he soon followed his mother’s example and converted to the Lutheran faith. Here, as on so many later occasions, dynastic women played a crucial role in the development of Brandenburg’s confessional policy.

For all his personal sympathy with the cause of religious reform, Joachim II was slow to attach his territory formally to the new faith. He

still loved the old liturgy and the pomp of the Catholic ritual. He was also anxious not to take any step that might damage Brandenburg’s standing within the fabric of the still predominantly Catholic Empire. A portrait from around 1551 by Lucas Cranach the Younger captures these two sides of the man. We see an imposing figure who stands with fists clenched before a spreading belly, decked in the bulging, bejewelled court garb of the day. There is watchfulness in the features. Wary eyes look out obliquely from the square face.

1. Lucas Cranach,

Elector Joachim II

(1535–71), painted

c.

1551

In the great political struggles of the Empire, Brandenburg aspired to the role of conciliator and honest broker. The Elector’s envoys were involved in various failed attempts to engineer a compromise between the Protestant and Catholic camps. Joachim II kept his distance from the more hawkish Protestant princes and even sent a small contingent of mounted troops to support the Emperor during the Schmalkaldic War. It was not until 1563, in the relative calm that followed the Peace of Augsburg, that Joachim formalized his personal attachment to the new religion through a public confession of faith.

Only in the reign of Elector John George (1571–98), Joachim II’s son, did the lands of Brandenburg begin to develop a more firmly Lutheran

character: orthodox Lutherans were appointed to professorial posts at the University of Frankfurt/Oder, the Church Regulation of 1540 was thoroughly revised to conform more faithfully with Lutheran principles and two territorial church inspections (1573–81 and 1594) were carried out to ensure that the transition to Lutheranism was accomplished at the provincial and local level. Yet in the sphere of imperial politics, John George remained a loyal supporter of the Habsburg court. Even Elector Joachim Frederick (r. 1598–1608), who as a young man had antagonized the Catholic camp by his open support for the Protestant cause, mellowed when he came to the throne, and kept his distance from the various Protestant combinations attempting to extract religious concessions from the imperial court.

11

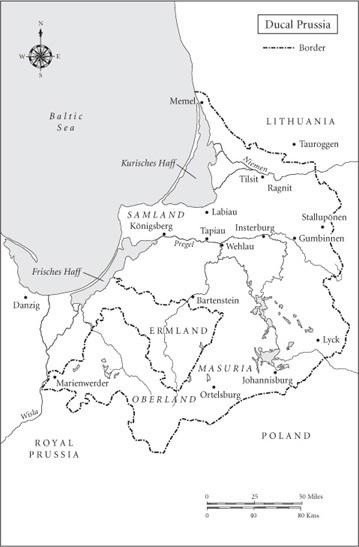

If the Electors of Brandenburg were prudent, they were not without ambition. Marriage was the preferred instrument of policy for a state that lacked defensible frontiers or the resources to achieve its objectives by coercive means. Surveying the Hohenzollern marital alliances of the sixteenth century, one is struck by the scatter-gun approach: in 1502 and again in 1523, there were marriages with the House of Denmark, by which the reigning Elector hoped (in vain) to acquire a claim to parts of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein and a harbour on the Baltic. In 1530, his daughter was married off to Duke Georg I of Pomerania, in the hope that Brandenburg might one day succeed to the duchy and acquire a stretch of Baltic coast. The King of Poland was another important player in Brandenburg’s calculations. He was the feudal overlord of the Duchy of Prussia, a Baltic principality that had been controlled by the Teutonic Order until its secularization in 1525, and was ruled thereafter by Duke Albrecht von Hohenzollern, a cousin of the Elector of Brandenburg.

It was partly in order to get his hands on this attractive territory that Elector Joachim II married Princess Hedwig of Poland in 1535. In 1564, when his wife’s brother was on the Polish throne, Joachim succeeded in having his two sons named as secondary heirs to the duchy. Following Duke Albrecht’s death four years later, this status was confirmed at the Polish Reichstag in Lublin, opening up the prospect of a Brandenburg succession to the duchy if the new duke, the sixteen-year-old Albrecht Frederick, were to die without male issue. As it happened, the wager paid off: Albrecht Frederick lived, in poor mental but good physical

health, for a further fifty years until 1618, when he died, having sired two daughters, but no sons.

In the meanwhile, the Hohenzollerns lost no time in reinforcing their claim to the Duchy of Prussia by every means available. The sons took up where the fathers had left off. In 1603, Elector Joachim Frederick persuaded the Polish king to grant him the powers of regent over the duchy (necessary because of the reigning duke’s mental infirmity). His son John Sigismund had further reinforced the link with Ducal Prussia by marrying Duke Albrecht Friedrich’s eldest daughter, Anna of Prussia, in 1594, overlooking her mother’s candid warning that she was ‘not the prettiest’.

12

Then, presumably in order to prevent another family from muscling in on the inheritance, the father, Joachim Frederick, whose first wife had died, married the younger sister of his son’s wife. The father was now the brother-in-law of the son, while Anna’s younger sister doubled as her mother-in-law.

A direct succession to the Duchy of Prussia thus seemed certain. But the marriage between John Sigismund and Anna also opened up the prospect of a new and rich inheritance in the west. Anna was not only the daughter of the Duke of Prussia, but also the niece of yet another insane German duke, John William of Jülich-Kleve, whose territories encompassed the Rhenish duchies of Jülich, Kleve (Cleves) and Berg and the counties of Mark and Ravensberg. Anna’s mother, Maria Eleonora, was the eldest sister of John William. The relationship on her mother’s side would have counted for little, had it not been for a pact within the house of Jülich-Kleve that allowed the family’s properties and titles to pass down the female line. This unusual arrangement made Anna of Prussia her uncle’s heiress, and thus established her husband, John Sigismund of Brandenburg, as a claimant to the lands of Jülich-Kleve.

13

Nothing could better illustrate the serendipitous quality of the marriage market in early modern Europe, with its ruthless trans-generational plotting, and its role in this formative phase of Brandenburg’s history.