Iron Kingdom : The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947 (81 page)

Read Iron Kingdom : The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947 Online

Authors: Christopher Clark

Britain was of course – as British travellers were forever pointing out – an incomparably more liberal polity, but it was not necessarily a more humane one. Britons tolerated levels of state violence that would have been unthinkable in Prussia. The number of condemnations to death in Prussia during the years from 1818 to 1847 fluctuated between twenty-one and thirty-three per annum. The number of actual executions was

much lower – it varied between five and seven – thanks to the intensive use of the royal pardon, which became an important mark of sovereignty in this period. By contrast, 1,137 death sentences were handed down every year on average over the period 1816–35 in England and Wales, whose combined population (around 16 million) was comparable to Prussia’s. To be sure, relatively few (less than 10 per cent) of these sentences were actually carried out, but the number of persons executed still exceeded the Prussian figure by a factor of sixteen-to-one. Whereas the great majority of English and Welsh capital sentences were passed for property crimes (including quite minor ones), most Prussian executions were for crimes of homicide. The only ‘political’ execution of the pre-revolutionary era was that of the village mayor Tschech, who was found guilty of high treason for having attempted to murder the king.

75

In short: there was no Prussian parallel to the routine slaughter perpetrated at the gallows under England’s ‘bloody code’.

Terrible as the extremes of poverty were in the ‘hungry forties’, they pale in comparison to the hunger catastrophe that ravaged British-administered Ireland. Today we blame this disaster on a combination of administrative error with the dynamics of the free market. Had such a mass famine been visited upon the Poles in Prussia, we would perhaps now be discerning in it the antecedents of post-1939 Nazi rule. It is also worth remembering that the Prussians faced constraints in Poland that had no counterpart in Ireland. Poland was the unquiet frontier between Prussia and the Russian Empire, and Prussian policy in the region had to take account of Russian interests. The Prussian Crown did not, of course, accept the legitimacy of Polish nationalist strivings. It did, however, accommodate the aspiration of its Polish subjects to cultivate their distinctive nationality. Indeed, the government’s promotion of Polish-language elementary and secondary schooling led to a dramatic rise in Polish literacy rates in the Prussian-occupied sector of the old Polish Commonwealth. There was, to be sure, a ten-year period when Provincial Governor Flottwell switched to a policy of assimilation through ‘Germanization’ – an ominous foretaste of later developments. But this was very inconsistently pursued, came to an end with the accession of the romantic Polonophile Frederick William IV and was in any case a response to the Polish revolution of 1830, which had raised serious doubts about the political loyalty of the province.

In the early 1840s, when Heine was living in literary exile in Paris,

Prussian Poland remained an attractive refuge for Polish political exiles from east of the Poznanian border. Russian dissidents, too, found their way to Prussia. The radical literary critic Vissarion Grigorevich Belinskii was living in Salzbrunn, Silesia in 1847 when he wrote his famous

Letter to Gogol

denouncing the political and social backwardness of his homeland, a crime for which he was condemned to death

in absentia

by a Russian court. So resonant was this cry of protest within Russian dissident circles that Turgenev, who visited Belinskii in Silesia, chose to sign ‘Bailiff’, the savage pen-portrait of a tyrannical landlord in

Sketches from a Hunter’s Album

, with ‘Salzbrunn, 1847’, a coded indication of his support for Belinskii’s critique. In the same year, another exile, the Russian radical Alexander Herzen, crossed the Prussian border from the east. Arriving in Königsberg, he expressed a profound sense of relief: ‘The unpleasant feelings of fear [and] the oppressive sense of suspicion were all dispelled.’

76

Splendour and Misery of the Prussian Revolution

By the end of February 1848, the population of Berlin was growing accustomed to the news of revolution. In the winter of 1847, Protestant liberals in Switzerland had fought – and won – a civil war against the conservative Catholic cantons. The result was a new Swiss federal state with a liberal constitution. Then, on 12 January 1848, after reports of unrest in the Italian peninsula, came the news that insurgents had seized power in Palermo. Two weeks later, the success of the Palermitan revolution was confirmed when the King of Naples became the first Italian monarch to offer his people a constitution.

It was above all the news from France that electrified the city. During February, a liberal protest campaign gained momentum in the French capital, culminating in bloody clashes between troops and demonstrators. On 28 February, an extra edition of Berlin’s

Vossische Zeitung

featured a ‘telegraphic despatch’ reporting that King Louis Philippe had abdicated. In view of the ‘current state of France and of Europe’, the editors declared, ‘this turn of events – so sudden, so violent and so utterly unexpected – appears more extraordinary, perhaps more momentous in its consequences than even the July Revolution [of 1830].’

1

As the news from Paris broke in the Prussian capital, Berliners poured on to the streets in search of information and discussion. The weather helped – these were the mildest and brightest early spring days that anyone could remember. Reading clubs, coffee-houses and public establishments of all kinds were crammed to bursting. ‘Whoever managed to get his hands on a new paper had to climb on to a chair and read the contents aloud.’

2

The excitement grew as word arrived of events closer to home – large demonstrations in Mannheim, Heidelberg, Cologne and other German

cities, the concession of political reforms and civil liberties by King Ludwig I of Bavaria, the dismissal of conservative ministers in Saxony, Baden, Württemberg, Hanover and Hesse.

One important focal point for debate and protest was the Municipal Assembly, where elected members of the burgher elite regularly met to discuss the affairs of the city. After 9 March, when a crowd forced its way into the City Hall, the usually rather stolid assembly began to mutate into a protest rally. There were also daily political meetings at the ‘Tents’, an area of the Tiergarten just outside the Brandenburg Gate reserved for outdoor refreshments and entertainments. These had begun as informal gatherings, but they soon took on the contours of an improvised parliament, with voting procedures, resolutions and elected delegations, a classical example of the ‘public meeting democracy’ that unfolded across the German cities in 1848.

3

It was not long before the Municipal Assembly and the Tents began to work together; on 11 March, the assembly discussed a draft petition from the Tents demanding a long list of political, legal and constitutional reforms. By 13 March, the gathering at the Tents, now numbering over 20,000, had begun to hear speeches from workers and artisans whose chief concern was not legal and constitutional reform, but the economic needs of the working populace. A gathering of workers at one corner formed a separate assembly and drew up a petition of its own pressing for new laws to protect labour against ‘capitalists and usurers’ and asking the king to establish a ministry of labour. Distinct political and social interests were already crystallizing within the mobilized crowd of the city.

Alarmed at the growing ‘determination and insolence’ of the crowds circulating in the streets, the President of Police, Julius von Minutoli, ordered new troops into the city on 13 March. That night, several civilians were killed in clashes around the palace precinct. The crowd and the soldiery were now collective antagonists in a struggle for control of the city’s space. Over the next few days, crowds flowed through the city in the early evenings. They were, in Manzoni’s memorable simile, like ‘clouds still scattered and scudding about a clear sky, making everyone look up and say that the weather has not yet settled’.

4

The crowd was afraid of the troops, but also drawn to them. It cajoled, persuaded and taunted them. The troops had their own elaborate rituals. When confronted by unruly subjects, they were required to read out the riot

act of 1835 three times, before giving three warning signals with the drum or the trumpet, after which the order to attack would be given. Since many of the men in the crowd had themselves served in the military, these signals were almost universally recognized and understood. The reading of the riot act was generally greeted with whistling and jeers. The beating of the drum, which signalled an imminent advance or charge, had a stronger deterrent effect but this was generally temporary. On a number of occasions during the struggles in Berlin, crowds forced troops standing guard to run through their warning routines over and over again by provoking them, melting away when the drum was sounded, then reappearing to start the game again.

5

42

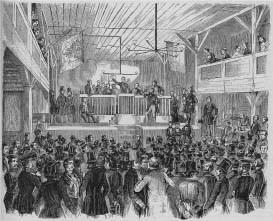

. From the club life of Berlin in 1848.

Contemporary engraving.

So poisonous was the mood in the city that men in uniform walking alone or in small groups were in serious danger. The liberal writer and diarist Karl August Varnhagen von Ense watched with mixed feelings from his first-floor window on 15 March as three officers walked slowly along the footpath of a street adjoining his house followed by a shouting crowd of about 200 boys and youths. ‘I saw how stones struck them,

how a raised staff crashed down on one man’s back, but they did not flinch, they did not turn, they walked as far as the corner, turned into the Wallstrasse and took refuge in an administrative building, whose armed guards scared the tormentors away.’ The three men were later rescued by a troop detachment and escorted to the safety of the city arsenal.

6

The military and political leadership found it difficult to agree on how to proceed. The mild and intelligent General von Pfuel, governor of Berlin, with responsibility for all troops stationed in and around the capital, favoured a mix of tact and political concessions. By contrast, the king’s younger brother, Prince William, urged the monarch to order an all-out attack on the insurgents. General von Prittwitz, commander of the King’s Lifeguards and a hard-line supporter of Prince William, later recalled the chaotic atmosphere that reigned at the court. The king, Prittwitz claimed, was buffeted about by the conflicting advice of a throng of advisers and well-wishers. The tipping point came with the news (breaking in Berlin on 15 March) that Chancellor Metternich had fallen, following two days of revolutionary upheaval in Vienna. Deferential as ever to Austria, the ministers and advisers around the king read this as an omen and resolved to offer further political concessions. On 17 March, the king agreed to publish royal patents announcing the abolition of censorship and the introduction of a constitutional system in the Kingdom of Prussia.

By this time, however, plans had already been laid for an afternoon rally to take place on the following day, 18 March, in the Palace Square. On that morning the government broadcast the news of its concessions across the city. Municipal deputies were seen dancing in the streets with members of the public. The city government ordered the illumination of the city that evening as a token of its gratitude.

7

But it was too late to stop the planned demonstration: from around noon, streams of people began to converge upon the Palace Square, including prosperous burghers and ‘protection officers’ (unarmed officials recruited from the middle classes and appointed to mediate between troops and crowds), but also many artisans from the slum areas outside the city boundaries. As the news of the government’s decisions circulated, the mood became festive, euphoric. The air was filled with the sound of cheering. The crowd, ever more densely packed in the warm sunlit square, wanted to see the king.

The mood inside the palace was light-hearted. When Police Chief Minutoli arrived at around one in the afternoon to warn the king that he believed a major upheaval was still imminent, he was met with indulgent smiles. The king thanked him for his work and added: ‘There is one thing I should say, my dear Minutoli, and that is that you always see things too negatively!’ Hearing the applause and cheering from the square, the king and his entourage made their way in the direction of the people. ‘We’re off to collect our hurrahs,’ quipped General von Pfuel.

8

At last the monarch walked out on to a stone balcony overlooking the square, where he was greeted with frenetic ovations. Then Prime Minister von Bodelschwingh stepped forward to make an announcement: ‘The king wishes freedom of the press to prevail! The king wishes that the United Diet be called immediately! The king wishes that a constitution on the most liberal basis should encompass all the German lands! The king wishes that there should be a German national flag! The king wishes that all customs turnpikes should fall! The king wishes that Prussia should place itself at the head of the movement!’ Most of the crowd could hear neither the king nor his minister, but printed copies of his recent patents were being passed through the throng and the wild cheering around the balcony soon spread across the square in a wave of elation.