Is Journalism Worth Dying For?: Final Dispatches

Read Is Journalism Worth Dying For?: Final Dispatches Online

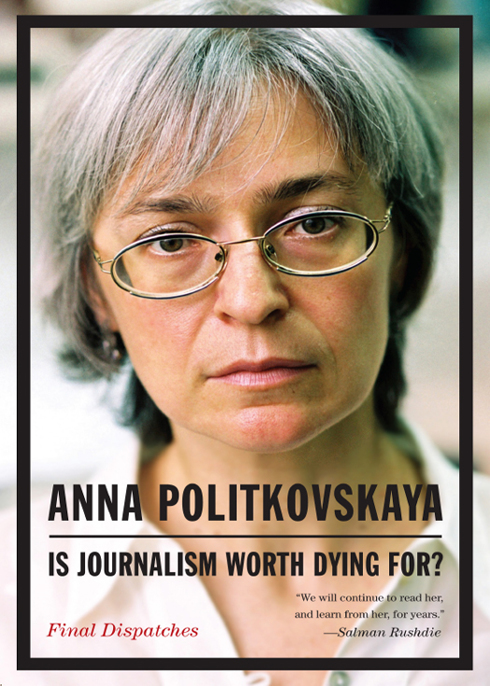

Authors: Anna Politkovskaya,Arch Tait

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union

Known by many as “Russia’s lost moral conscience” and hailed by the

New York Times

as “the bravest of journalists,”

ANNA POLITKOVSKAYA

(born 1958 in New York City) was a special correspondent for the Russian newspaper

Novaya gazeta

. She received honors from many Russian and international groups, including Amnesty International and the Index on Censorship. In 2000 she received Russia’s prestigious Golden Pen Award for her coverage of the war in Chechnya, and in 2005 she was awarded the Civil Courage Prize. She is the author of

A Dirty War; A Small Corner of Hell; Putin’s Russia;

and

A Russian Diary

. She was murdered in Moscow on October 7, 2006.

ARCH TAIT

translates from the Russian. His translation of Ludmila Ulitskaya’s

Sonechka: A Novella and Stories

was shortlisted for the Rossica Translation Prize in 2007.

Also by Anna Politkovskaya

A Russian Diary

Putin’s Russia

A Small Corner of Hell: Dispatches from Chechnya

A Dirty War: a Russian Reporter in Chechnya

IS JOURNALISM WORTH DYING FOR?

Originally published in Russian as

Za chto?

by

Novaya gazeta

, Moscow, 2007

© 2007 Anna Politkovskaya

© 2007

Novaya gazeta

Translation © 2010 by Arch Tait

First Melville House printing: March 2011

Melville House Publishing

145 Plymouth Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201

eISBN: 978-1-935554-70-7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011922469

v3.1

This book was first published in Russian as

Za chto

—What For?—by

Novaya gazeta

, the newspaper to which Anna Politkovskaya contributed from June 1999 until her murder in October 2006. Her colleagues at the paper assembled the collection, and their reminiscences of Politkovskaya and investigation of her murder (including Vyacheslav Izmailov’s “Who Killed Anna and Why?”) are also included. Politkovskaya is one of four

Novaya gazeta

journalists murdered between 2001 and 2009.

CONTENTS

1. Should Lives Be Sacrificed to Journalism

Part I: Dispatches from the Frontline

Part II: The Protagonists

Part III: The Kadyrovs

7. Planet Earth: The World Beyond Russia

She represented the honor and conscience of Russia, and probably nobody will ever know the source of her fanatical courage and love of the work she was doing.

Liza Umarova, Chechen singer

Anna rang me at the hospital in the morning, before 10 o’clock. She was supposed to be coming to visit, this was her day, but something had come up at home. Anna said my second daughter, Lena, would come instead, and promised that we would definitely meet on Sunday. She sounded in a good mood, her voice was cheerful. She asked how I was feeling and whether I was reading a book. She knew I love historical literature and had brought me Alexander Manko’s

The Most August Court under the Sign of Hymenaeus

. She had not read it herself. I said, “Anya, it is difficult for me to read. I have to read every page three times because I have Father before my eyes all the time.” [Raisa Mazepa’s husband had died shortly before.] She tried to calm me, “He didn’t suffer. Everything happened very quickly. He was coming to visit you. Let’s talk about the book instead.” I said, “Anya there is an epigraph on page 179 which really moves me. It is so much a part of us, so Russian.” I read it to her: “There are drunken years in the history of peoples. You have to live through them, but you can never truly live in them.”

“Oh, Mum,” she replied, “put a bookmark there, don’t forget.” I asked my daughter who the author of the epigraph was, and she told me about Nadezhda Teffi, a famous Russian poetess. Then she said, “Speak to you tomorrow, Mum.” She was in a very good mood. Or perhaps she was in a bad mood and just pretending everything was fine in order not to upset me.

I was always very worried about her. Shortly before I went into hospital we had a talk. She was preparing an article about Chechnya, and I simply begged her to be careful. I remember she said, “Of course I know the sword of Damocles is always hanging over me. I know it, but I won’t give in.”

Raisa Mazepa (Anna Politkovskaya’s mother),

Novaya gazeta

,

October 23, 2006

SO WHAT AM I GUILTY OF?

This article was found in Anna Politkovskaya’s computer after her death and is addressed to readers abroad

.

“Koverny

,” a Russian clown whose job in the olden days was to keep the audience laughing while the circus arena was changed between acts. If he failed to make them laugh, the ladies and gentlemen booed him and the management sacked him.

Almost the entire present generation of Russian journalists, and those sections of the mass media which have survived to date, are clowns of this kind, a Big Top of

kovernys

whose job is to keep the public entertained and, if they do have to write about anything serious, then merely to tell everyone how wonderful the Pyramid of Power is in all its manifestations. The Pyramid of Power is something President Putin has been busy constructing for the past five years, in which every official – from top to bottom, the entire bureaucratic hierarchy – is appointed either by him personally or by his appointees. It is an arrangement of the state which ensures that anybody given to thinking independently of their immediate superior is promptly removed from office. In Russia the people thus appointed are described by Putin’s Presidential Administration, which effectively runs the country, as “on side.” Anybody not on side is an enemy. The vast majority of those working in the media support this dualism. Their reports detail how good on-side people are, and deplore the despicable nature of enemies. The latter include liberally inclined politicians, human rights activists, and “enemy” democrats, who are generally characterised as having sold out to the West. An example of an on-side democrat is, of course, President Putin himself. The newspapers and television give top priority to detailed “exposés” of the grants enemies have received from the West for their activities.

Journalists and television presenters have taken enthusiastically to their new role in the Big Top. The battle for the right to convey

impartial information, rather than act as servants of the Presidential Administration, is already a thing of the past. An atmosphere of intellectual and moral stagnation prevails in the profession to which I too belong, and it has to be said that most of my fellow journalists are not greatly troubled by this reversion from journalism to propagandising on behalf of the powers that be. They openly admit that they are fed information about enemies by members of the Presidential Administration, and are told what to cover and what to steer clear of.

What happens to journalists who don’t want to perform in the Big Top? They become pariahs. I am not exaggerating.

My last assignment to the North Caucasus, to report from Chechnya, Ingushetia, and Dagestan, was in August 2006. I wanted to interview a senior Chechen official about the success or failure of an amnesty for resistance fighters which the Director of the Federal Security Bureau, the FSB, had declared.

I scribbled down an address in Grozny, a ruined private house with a broken fence on the city’s outskirts, and slipped it to him without further explanation. We had talked in Moscow about the fact that I would be coming and would want to interview him. A day later he sent someone there who said cryptically, “I have been asked to tell you everything is fine.” That meant the official would see me, or more precisely that he would come strolling in carrying a string bag and looking as if he had just gone out to buy a loaf of bread.

His information was invaluable, and completely undermined the official account of how the amnesty was going. It was conveyed to me in a room two metres square with a tiny window whose curtains were firmly drawn. Before the war it had been a shed, but when the main house was bombed its owners had to use it as kitchen, bedroom and bathroom combined. They let me use it with considerable trepidation, but they are old friends about whose misfortunes I wrote some years ago when their son was abducted.

Why did the official and I go to these lengths? Were we mad, or trying to bring a little excitement into our lives? Far from it. Open fraternisation between an opposition-inclined gatherer of information

like me or another of my

Novaya gazeta

colleagues and an on-side government official would spell disaster for both of us.

That same senior official subsequently brought to the sometime shed resistance fighters who wanted to lay down their arms but not to take part in the official circus performance. They passed on a lot of interesting information about why none of the fighters wanted to surrender to the regime: they believed the Government was only interested in public relations and could not be trusted.

“Nobody wants to surrender!” The pundits will find that hard to believe. For weeks Russian television has shown dodgy-looking individuals declaring that they want to accept the amnesty terms, that they “trust Ramzan.” Ramzan Kadyrov is President Putin’s Chechen favorite, appointed Prime Minister with blithe disregard for the fact that the man is a complete idiot, bereft of education, brains, or a discernible talent for anything other than mayhem and violent robbery.

To these unholy gatherings squads of journalist-clowns are brought along (I don’t get invited). They write everything down carefully in their notebooks, take their photographs, file their reports, and a totally distorted image of reality results. An image, however, which is pleasing to those who declared the amnesty.

You don’t get used to this, but you learn to live with it. It is exactly the way I have had to work throughout the Second War in the North Caucasus. To begin with I was hiding from the Russian federal troops, but always able to make contact clandestinely with individuals through trusted intermediaries, so that my informants would not be denounced to the generals. When Putin’s plan of Chechenisation succeeded (setting “good” Chechens loyal to the Kremlin to killing “bad” Chechens who opposed it), the same subterfuge applied when talking to “good” Chechen officials. The situation is no different in Moscow, or in Kabardino-Balkaria, or Ingushetia. The virus is very widespread.

At least a circus performance does not last long, and the regime availing itself of the services of clownish journalists has the longevity of a mouldering mushroom. Purging the news has produced a blatant lie orchestrated by officials eager to promote a “correct image of Russia under Putin.” Even now it is producing tragedies the regime cannot

cope with and which can sink their aircraft carrier, no matter how invincible it may appear. The small town of Kondopoga in Karelia, on the border with Finland, was the scene of vodka-fuelled anti-Caucasian race riots which resulted in several deaths. Nationalistic parades and racially motivated attacks by “patriots” are a direct consequence of the regime’s pathological lying and the lack of any real dialogue between the state authorities and the Russian people. The state closes its eyes to the fact that the majority of our people live in abject poverty, and that the real standard of living outside of Moscow is much lower than claimed. The corruption within Putin’s Pyramid of Power exceeds even the highs previously attained, and a younger generation is growing up both ill-educated, and militant because of their poverty.