Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia (20 page)

Read Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia Online

Authors: David Vine

Tags: #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural, #Political Science, #Human Rights, #History, #General

At 10:00 a.m. Washington time, on Tuesday, December 15, the Nixon White House for the first time publicly announced the United States’ intention to build a joint U.S.-U.K. military facility on Diego Garcia. The State and Defense departments provided embassies with a list of anticipated questions and suggested answers to handle press inquiries, including the following:

Q: What is the purpose of the facility?

A: To close a gap in our worldwide communications system and to provide communications support to U.S. and U.K. ships and aircraft in the Indian Ocean.

Q: Is this part of a U.S. buildup in the Indian Ocean?

A: No.

Q: Will other facilities be built in this area?

A: No others are contemplated.

Q: What will happen to the population of Diego Garcia?

A: The population consists of a small number of contract laborers from the Seychelles and Mauritius engaged to work on the copra plantations. Arrangements will be made for the contracts to be terminated at the appropriate time and for their return to Mauritius and Seychelles.

30

AN ORDER

If, as Earl Ravenal indicated with one of today’s ubiquitous sports metaphors, Paul Nitze helped get the plan for Diego Garcia moving as Secretary of the Navy (in fact he started even earlier at ISA) and got the base

funded as Deputy Secretary of Defense, the man who saw the project to its completion was Admiral Elmo Zumwalt.

Born in San Francisco in 1920 to two doctors, Elmo Russell Zumwalt, Jr., a prep school valedictorian and Naval Academy graduate, enjoyed an unprecedented rise to the top of the Navy hierarchy. At 44, Zumwalt was the youngest naval officer to be promoted to Rear Admiral. At 49, Zumwalt became the Navy’s youngestever four-star Admiral and the youngestever CNO. His record of awards, decorations, and honorary degrees runs a single-spaced page, including medals from France, West Germany, Holland, Argentina, Brazil, Greece, Italy, Japan, Venezuela, Bolivia, Indonesia, Sweden, Colombia, Chile, South Korea, and South Vietnam.

31

As CNO from 1970 to 1974, Zumwalt gained attention for integrating the Navy, for upgrading women’s roles, and for relaxing naval standards of dress in keeping with the times. In an order to the Navy entitled “Equal Opportunity in the Navy,” Zumwalt acknowledged the service’s discriminatory practices against African Americans and ordered corrective actions. “Ours must be a Navy family that recognizes no artificial barriers of race, color or religion, “Zumwalt wrote in what was a pathbreaking statement for the U.S. armed forces. “There is no black Navy, no white Navy—just one Navy—the United State Navy.”

32

Nitze originally recruited Zumwalt in 1962 to work under him when Nitze was Assistant Secretary of Defense at ISA. In his memoirs, Zumwalt describes working closely with his “mentor and close friend.” Zumwalt eventually following Nitze to his position as Secretary of the Navy, as Nitze’s Executive Assistant and Senior Aide. Zumwalt was “at Paul’s side” during the Cuban Missile Crisis and negotiations leading to the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. Under Nitze’s “tutelage,” Zumwalt writes, he earned a “Ph.D. in political-military affairs.”

33

Nitze, for his part, rewarded Zumwalt by recommending him to receive the rear admiral’s second star two years before others in his Naval Academy class were eligible and without having commanded a destroyer squadron or cruiser, as was the Navy’s tradition.

34

Upon becoming the Navy’s youngestever rear admiral, Zumwalt commanded a cruiser-destroyer flotilla and later became Commander of U.S. Naval Forces in Vietnam before his promotion by President Nixon to CNO.

Zumwalt worked on Diego Garcia from his time with Nitze at ISA and maintained the same interest in the base once he left Nitze’s staff.

35

One of Zumwalt’s staffers, Admiral Worth H. Bagley, remembered in 1989 how Zumwalt wanted to boost the U.S. naval presence in the Indian Ocean, in part out of concern for the “growing reliance on high oil imports at a time

when things were looking unstable.” Helped by the 1971 war between India and Pakistan, Zumwalt increased the pace of deployments in the ocean.

“He went out himself and visited the . . . African countries,” Bagley explained. “Looking into the question of bases and things of that sort. . . . To see if he could find some economical way to increase base and crisis support possibilities there.”

36

“In dealing with Diego Garcia also?” Bagley’s interviewer suggested.

“Moorer did that. Zumwalt finished it up for him,” Bagley replied.

37

And so Zumwalt did. Once Nitze and Admiral Moorer had secured funding from Congress, Zumwalt focused on removing Diego Garcia’s population to prevent any construction delays. At a December 10, 1970 meeting, CNO Zumwalt told his deputies that he wanted to “push the British to get the copra workers off Diego Garcia prior to the commencement of construction,” scheduled to begin in March 1971.

38

A secret letter confirmed British receipt of the order to remove the Chagossians: “The United States Government have recently confirmed that their security arrangements at Diego Garcia will require the removal of the entire population of the atoll. . . . This is no surprise. We have known since 1965 that if a defence facility were established we should have to resettle elsewhere the contract copra workers who live there.”

39

As both governments prepared for the deportations and the start of construction, the U.S. embassies in London and Port Louis began recommending that the Navy use some Chagossians as manual laborers for the construction. Zumwalt refused. Two days after his December 17 order redressing racial discrimination in the Navy, Zumwalt stressed that by the end of construction all inhabitants should be moved to their “permanent other home.”

In a small note handwritten on the face of Zumwalt’s memo, a deputy commented, “Probably have no permanent other home.”

40

As planning proceeded into January 1971, Zumwalt received a memorandum from the State Department’s Legal Adviser, John R. Stevenson, bearing on the deportations and the speed with which they would be accomplished. In the memo, Stevenson discussed “several legal considerations affecting US-UK responsibilities toward the 400 inhabitants of Diego Garcia.” He pointed out that the 1966 U.S.-U.K. agreement “provides certain safeguards for the inhabitants,” noting as well the commitment of both nations under the UN Charter to make the interests of inhabitants living in non–selfgoverning territories “paramount”:

Although the responsibility for carrying out measures to ensure the welfare of the inhabitants lies with the UK, the US is charged under

the [1966] Agreement with facilitating these arrangements. London 10391 [embassy memo] states that the US constrained the UK from discussing the matter with the GOM pending the outcome of our Congressional appropriations legislation. In light of this, we are under a particular responsibility not to pressure the UK into meeting a time schedule which may not provide sufficient time in which to satisfactorily arrange for the welfare of the inhabitants. Beyond this, their removal is to accommodate US needs, and the USG will, of course, be considered to share the responsibility with the UK by the inhabitants and other nations if satisfactory arrangements are not made.

41

A day after Zumwalt received Stevenson’s warning, two Navy officials were in the Seychelles to meet with the commissioner and administrator of the BIOT, Sir Bruce Greatbatch and John Todd. Together, they made plans for emptying the western half of Diego Garcia before the arrival of Navy “Seabee” construction teams, the “segregation” of Chagossians from the Seabees, and the “complete evacuation” of Diego Garcia by July.

42

Greatbatch and Todd explained that this was the fastest they could get rid of the population other than to “drop Ilois on pier at Mauritius and sail away quickly.”

43

Two weeks later a nine-member Navy reconnaissance party arrived on Diego Garcia with Todd and Moulinie & Co. director Paul Moulinie. On January 24, Todd and Moulinie ordered everyone on the island to the manager’s office at East Point. Dressed in white and perched on the veranda of the office overlooking the assembled crowd, Todd announced that the BIOT was closing Diego Garcia and the plantations. The BIOT, he added, would move as many people as possible to Peros Banhos and Salomon.

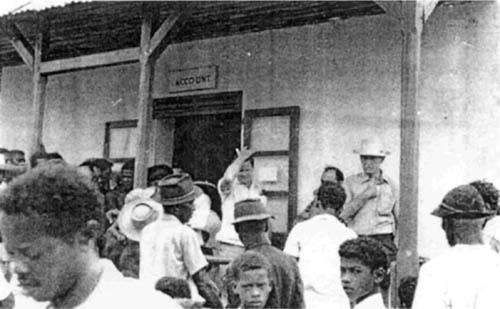

A black-and-white photograph of the scene shows the islanders staring in disbelief (see

figure 6.1

). Some “of the Ilois asked whether they could return to Mauritius instead and receive some compensation for leaving their ‘own country.’”

44

Not unlike the Bikinians before them, most were simply stunned.

45

When given the “choice” between deportation to Mauritius or to Peros Banhos or Salomon, most elected to remain in Chagos. Many Seychellois workers and their Chagos-born children were deported to the Seychelles. Some Chagossians resigned themselves to deportation directly to Mauritius.

Many Chagossians say that they were promised land, housing, and money upon reaching Mauritius.

46

Moulinie’s nephew and company employee Marcel Moulinie swore in a 1977 court statement that he “told the

labourers that it was quite probable that they would be compensated.” He continued, “I do not recall saying anything more than that. I was instructed to tell them that they had to leave and that is what I did.”

47

Figure 6.1 Closing Diego Garcia, January 24, 1971. The BIOT announces the deportations, John Todd at center, hand on forehead; Paul Moulinie at right, in white hat. Courtesy Chagos Refugees Group, Willis Prosper.

Within days, a Navy status report detailed the progress of the deportations:

Relocation of the copra workers is proceeding in a satisfactory manner. The Administrator of the BIOT has given his assurance that the three small settlements on the western half of the atoll will be moved immediately to the eastern half. All copra producing activities on the western half will also cease immediately. The BIOT ship NORDVAER is relocating people from Diego Garcia to Peros Banhos, Salomon Islands, and the Seychelles on a regular basis.

48

On February 4, a State-Defense message directed all government personnel to “Avoid all direct participation in resettlement of Ilois on Mauritius.” The cable explained that “basic responsibility [is] clearly British,” and that the United States was under “no obligation [to] assist with” the resettlement. On the other hand, the departments conceded, the government had some obligation to give the British “sufficient time” to adequately ensure

the welfare of the islanders. “USG also realizes,” the telegram stated, “it will share in any criticism levied at the British for failing to meet their responsibilities re inhabitants’ welfare.”

49

The image placed here in the print version has been intentionally omitted

Figure 6.2 CNO Comment Sheet, Admiral Elmo Russell Zumwalt, Jr., Navy Yard, Washington, DC, 1971. Naval Historical Center.

ECHOES OF CONRAD

The pace of deportations continued unabated, and within a few months, Marcel Moulinie and other company agents had forced all Chagossians on the western side of Diego Garcia, including the villages of Norwa and Pointe Marianne, to leave their homes and land to resettle on the eastern side of the atoll.

50

On March 9, a landing party arrived on Diego to prepare for the arrival of a Seabee construction battalion later that month. Within days, unexpected reports came back to Navy headquarters from the advance team.

The commander “warns of possible bad publicity re the so-called ‘copra workers,’” a Deputy CNO wrote. “He cites . . . fine old man who’s been there 50 years. There’s a feeling the UK haven’t been completely above board on this. We don’t want another Culebra,” he said, referring to the opposition and negative publicity faced by the Navy during major protests

in Puerto Rico against 1970 plans to deport Culebra’s people and use their island as a bombing range.

51

“Relocation of persons,” Captain E. L. Cochrane, Jr. admitted to the Deputy CNO four days after the Seabees began construction, “is indeed a potential trouble area and could be exploited by opponents to our activities in the Indian Ocean.” He added, “A newsman so disposed could pose questions that would result in a very damaging report that long time inhabitants of Diego Garcia are being torn away from their family homes because of the construction of a sinister U.S. ‘base.’”

52