Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia (28 page)

Read Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia Online

Authors: David Vine

Tags: #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural, #Political Science, #Human Rights, #History, #General

The WHO-funded study found that Chagossians suffer from elevated levels of chronic colds, fevers, respiratory diseases, anemia, and transmissible diseases like tuberculosis, as well as problems with cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, hypertension, work accidents, and youth alcohol and tobacco abuse. The report found children and the elderly particularly vulnerable to disease, including water-borne diseases tied to poor hygiene and contaminated water supplies like infant diarrhea, hepatitis A, and intestinal parasites. The people also exhibited a large number of work accidents, most likely related to the physical labor and limited work protections many face.

7

At the same time, the study found that Chagossians don’t enjoy the same access to health care services as others in Mauritius because of their poverty, their limited knowledge of the health care system, and their limited confidence in both health care providers and the efficacy and quality of treatment.

8

Around 85 percent of the Chagossians that I surveyed reported needing more health care—more than any other reported social service need.

9

Sandra Cheri is a Chagossian nurse and one of few people qualified to comment professionally on the state of Chagossian health (she is also one of the few islanders in Mauritius with a government or semiprofessional job). I asked Sandra about common health problems experienced by the islanders. She listed diarrhea and vomiting, gastroenteritis, fevers, and influenza—illnesses they share with people throughout Mauritius. But Sandra said Chagossians also suffer from a high incidence of diabetes and hypertension because of dietary changes experienced since arriving in Mauritius. In Chagos, she said, there was no stress and the food was different (fish

even tasted better, she and others said). Nor was there hard alcohol, only wine and homemade brews like

baka

and

calou

.

In Mauritius, she said, there’s rum and whiskey and “many, many Chagossians are alcoholics.” She sees many at her hospital and in Cassis, where she finds them stumbling and drunk, shoeless and dirty along the road. Mauritians exploit many of them, Sandra added, knowing that they will work for a few rupees just to buy a Rs60 (around $2) bottle of rum.

Visibly intoxicated men are a common sight in Mauritius and the Seychelles, and most Chagossians attest to substance abuse as a serious problem in the community. In 2002 and 2003, we asked survey respondents if they needed help or treatment for an alcohol or drug problem, well aware that survey questions asking about substance abuse are renowned for underreporting actual use. The response was striking: One in every five volunteered having a problem. Less than two percent said they were receiving such treatment.

10

“There wasn’t sickness” like strokes or

sagren

, we remember Rita saying. “There wasn’t that sickness. Nor diabetes, nor any such illness. What drugs?” she asked me rhetorically, having lost Alex and Eddy to drug and alcohol abuse. At worst, she said, “If by chance you got drunk” and fell asleep “and you went to get your money—your cash—you would find it untouched when you awoke. No one would take it. No one would steal anything from another Chagossian. This is what my husband remembered and pictured in his mind. Me too, I remember these things that I’ve said about us, David. My heart grows heavy when I say these things, understand?”

As Rita’s words and the prevalence of substance abuse suggest, when people contrast a life filled with illnesses and drugs with a nearly disease-free life in Chagos, the comparison represents more than an accurate depiction of rising morbidity and declining health. The contrast also represents a commentary on and implicit critique of the expulsion. It represents a sign and recognition of the emotional and psychological damage the expulsion has caused.

“What must be heard” at the “emotional core” of stories of displacement, says psychiatrist Mindy Fullilove in the context of displacement caused by urban renewal in the United States, “is the howl of amputations, the anguish at calamity unassuaged, the fear of spiraling downward without cessation, and the rage at poverty imposed through repeated dispossession.”

11

For many Chagossians, the illnesses that they and their relatives and friends have experienced have come to represent all the difficulties of life in exile and the pain of being separated from their homeland. Illness, disease, and substance abuse have become metaphors, synecdoches—with one part representing the whole—for all the suffering of the expulsion.

EMBODIED ILLNESS

“So many troubles. My head went, went to a mental hospital. I already went before to a mental hospital, where I had shocks.”

“Shocks?” I asked, fearing that Rita meant electroshock therapy.

“I had too many troubles.”

“You got shocks?” I asked again.

“Yes.”

“What happened?”

“The same, the same deal like before. I got the treatment. My children didn’t have food in the house, and one by one they were dying like dead coconuts falling from the tree. So they gave me shocks.”

When Chagossians like Rita describe people dying of

sagren

, they are not just speaking metaphorically. The Chagos Refugees Group, which represents the vast majority of the community in Mauritius, has an “Index of Deceased Chagossians” listing the names of Chagossians who have died in exile. For 396 of the deceased individuals, as of 2001, a cause of death was indicated. In 60 of these cases, the cause of death was listed as wholly or in part due to “sadness” or “homesickness.”

12

“The notion of

sagren

has an important place in the explanative system for illness,” the WHO-funded study reports:

Sagren

“explains illness and even the deaths of members of the community.”

Sagren

is “nostalgia for the Chagos islands. It is the profound sadness of facing the impossibility of being able to return to one’s home in the archipelago.” The WHO report cites the case of one elderly man who died after suffering from diabetes, hypertension, and paralysis for many years. Before his death he only left his home once every three months when an ambulance drove him to get treatment. After his death, one of his friends said he had died of

sagren

. “Knowing that he would never again return to the island of his birth, he had preferred to let himself die.”

13

Sagren

is an example of what Fullilove has called the “root shock” of forced displacement.

Root shock is the traumatic stress reaction to the destruction of all or part of one’s emotional ecosystem. It has important parallels to the physiological shock experienced by a person who, as a result of injury, suddenly loses massive amounts of fluids. Such a blow threatens the whole body’s ability to function. The nervous system attempts to compensate for the imbalance by cutting off circulation to the arms and legs. Suddenly the hands and feet will seem cold

and damp, the face pale, and the brow sweaty. This is an emergency state that can preserve the brain, the heart, and the other essential organs for only a brief period of time. If the fluids are not restored, the person will die. Shock is the fight for survival after a life-threatening blow to the body’s internal balance.

14

With other symptoms that include wasting and weakness, confusion and disorientation, sadness and depression, shaking and paralysis, often ultimately resulting in death,

sagren

also resembles the affliction of

nervos

found among many in the world, but especially among the poor and marginalized in the Mediterranean and Latin America. Medical anthropologist Nancy Scheper-Hughes has shown through work with the poor in northeast Brazil how nervos is far from a matter of somatization or malingering, at least as they are typically understood by medical professionals. Nervos is instead “a collective and embodied response” to poverty and hunger and to a corrupt, violent political system that colludes to entrap the poor in these conditions—what she calls everyday forms of violence.

15

The roots of such afflictions are not psychological, as those who administered Rita’s electroshock therapy likely thought. The roots of such afflictions are social, political, and economic, with forms of violence like displacement becoming embodied by victims.

DYING OF

SAGREN

As the sometimes fatal illnesses of root shock and nervos indicate, Chagossians are not alone in finding that forms of grief and sadness can cause death. “There is little doubt,” Theodore Scudder and Elizabeth Colson explain, “that relocatees often believe that the elderly in particular are apt to die ‘of a broken heart’ following removal.” Importantly, this belief appears to have medical support: “The evidence is highly suggestive” that sadness can cause death “for Egyptian and Sudanese Nubians . . . and the Yavapai. . . . Elderly persons forced into nursing homes or forcibly removed from one nursing home to another are reported to have high mortality rates in the period immediately succeeding the move.”

16

Other research has shown that acute stress can bring on fatal heart spasms in people with otherwise healthy cardiac systems.

17

Among Hmong refugees in the United States who fled Laos in the 1970s, Sudden Unexpected Death Syndrome was the leading cause of death for years after their arrival. The syndrome is “triggered by cardiac failure, often during or after

a bad dream. No one has been able to explain what produces the cardiac irregularity, although theories over the years have included potassium deficiency, thiamine deficiency, sleep apnea, depression, culture shock, and survivor guilt.”

18

In my own family, my grandmother, Tea Stiefel, reminded me recently how her mother, Elly Eichengruen, died of a broken heart. A German Jew who fled to the United States in 1941, just before the outbreak of World War II, Elly never recovered from the guilt she felt for sending her 13-year-old son, Erwin, to Amsterdam a year earlier, where he was ultimately deported to Auschwitz and murdered. After learning of his fate, Elly never talked about her son. In 1947 she had a major heart attack and spent six weeks in a hospital unable to move. For the next ten years she lived as an invalid under my grandmother’s care until her death in 1957. When she died, her doctor said that she had died of a broken heart. “The guilt she carried with her ultimately just broke her heart,” my grandmother said. “Yes. It’s possible.”

Ranjit Nayak’s work with the Kisan of eastern India provides more evidence of the connections between the grief of exile and health outcomes, between mental and physical health. “The severance of the Kisan bonds from their traditional lands and environment is a fundamental factor in their acute depression and possibly in increased mortality rates, including infant mortality,” Nayak writes. Like Chagossians grieving for their lost origins in Chagos, for the Kisan, “a continuous pining for lost land characterizes the elderly. Anxiety, grieving, various neuropsychiatric illness and post-traumatic stress disorders feature among the Kisan. In essence, they suffer from profound cultural and landscape bereavement for their lost origins.”

19

This is what Scudder refers to among displacees as the “grieving for a lost home” syndrome.

20

For many, the intimacy of their connection to Chagos is closely related to the fact that their ancestors are buried on the islands. Repeatedly since the expulsion, Chagossians have requested permission to visit the islands to clean and tend to the graves of their ancestors. In 1975, hundreds petitioned the British and U.S. governments for aid and the right to go back to their islands. If they were to be barred from returning they asked the governments to at least “allow two or three persons from among us to go clean the cemetery at Diego Garcia where our forefathers, brother, sisters, mothers and fathers are buried, and to enable us to take care of the Diego Church where we were baptised.”

21

Janette Alexis, who was forced to leave Diego Garcia for the Seychelles as an adolescent, said she can see in her elders the pain of not going to

the graves of their ancestors. Being barred from visiting their graves and bringing them flowers, she said, being separated from one’s ancestors is yet another blow to their entire way of life. As Nayak writes of the Kisan, “In essence, they suffer from profound cultural and landscape bereavement for their lost origins.”

22

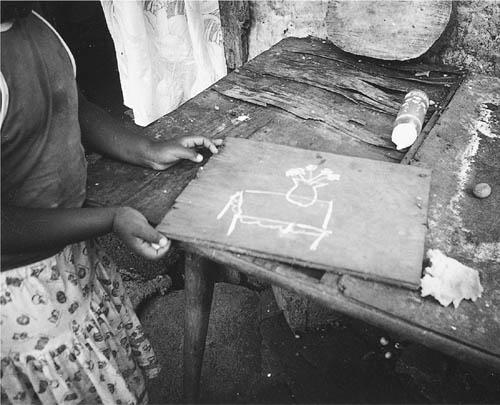

Figure 10.1

Flowers on a Table

, drawing, Baie du Tombeau, Mauritius, 2002. Photo by author.