It Chooses You (5 page)

Raymond: I can bring it down.

Miranda: We can go up there. I don’t want you to have to bring it down.

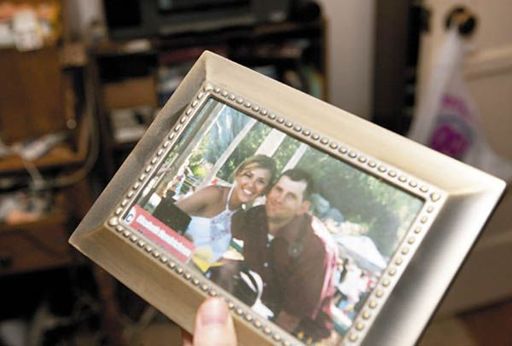

As we climbed the stairs, I began to realize the grandeur of the house was an illusion. These were the poor relations of the former owner. The mother and grandson both kept food and small refrigerators in their rooms, living in them like tiny studio apartments with a shared kitchen and bathroom. Before we looked at the mannequin, Raymond showed me a picture of himself with the actress Elizabeth Hendrickson from

All My Children

.

Raymond: I met her at Disneyland. We had to get in line and we had to wait two hours.

Miranda: What is she like? What do you like about her?

Raymond: She’s friendly. And she’s beautiful, she’s pretty.

Then he showed me the mannequin. It looked just like Elizabeth Hendrickson.

Miranda: So this — I mean, it kind of looks like her. Why does it look so much like her?

Raymond: I took this from this picture here.

Miranda: So did you make her face?

Raymond: My boss.

Miranda: Oh, your boss.

Raymond: Yeah, he made her.

Miranda: From the picture. And did he do that just for you?

Raymond: Yeah.

Miranda: Oh, that’s nice.

Raymond: He put it in the mold.

Miranda: Is that expensive? I mean, did you have to buy that?

Raymond: If a regular person would buy it, it would probably be about fifteen hundred dollars. He gave me a discount.

Miranda: I see you have two computers. What do you do on your computers?

Raymond: I email. I email my friends. Sometimes I email my sister if I have a question. And I download music.

Miranda: What kind of music?

Raymond: Dido.

Miranda: She’s cool.

Raymond: It’s too bad Michael Jackson passed away.

Miranda: Yeah.

Raymond: I’m heartbroken because of it.

Miranda: Right before his big tour.

Raymond: That’s my generation.

Miranda: How old are you?

Raymond: I’m thirty-nine.

Miranda: I’m thirty-five.

Raymond: So it’s our generation.

Miranda: Right.

It was a relief, meeting someone whom I had anything at all in common with. Michael and Primila and Pauline had exhausted me with their openness and their quaint inefficiency, but Raymond and I were the same generation; we both knew how to click on things, we both had a version of our name with @ in it. As I left his room I said something like “Maybe I’ll see you around,” as if our generation all liked to congregate at one coffee shop.

But the moment I got back in my car I knew I would never see him again, ever. It suddenly seemed obvious to me that the whole world, and especially Los Angeles, was designed to protect me from these people I was meeting. There was no law against knowing them, but it wouldn’t happen. LA isn’t a walking city, or a subway city, so if someone isn’t in my house or my car we’ll never be together, not even for a moment. And just to be absolutely sure of that, when I leave my car my iPhone escorts me, letting everyone else in the post office know that I’m not really with them, I’m with my own people, who are so hilarious that I can’t help smiling to myself as I text them back.

Not that I was meeting one kind of person though the

PennySaver

, or that they all sold things for the same reason. Michael was poor, Pauline was lonelier than she was poor, Primila was just old-fashioned. But so far there was one commonality, something so obvious it had taken me a moment to notice. In the process of trying to reassure the people I was calling, I would occasionally mention that I was somewhat established — not a student, but a published writer. Google “Miranda July,” I’d suggest (I do it all day long!). But they weren’t googlers. People who place ads in the print edition of the

PennySaver

don’t have computers — of course they don’t, or they’d just use Craigslist.

And as I circled and crossed out ads, the newsprint booklet itself began to seem like some vestigial relic. On one future Tuesday the number of computerless people would become too small, and the booklet would simply not arrive. This made me a little anxious, so I called up

PennySaver

headquarters and asked them if they would be around forever. “The

PennySaver

in concept will be here forever,” said Loren Dalton, the president of PennySaver USA (which actually serves only California), “but not necessarily in print. That’s why we’ve made pretty heavy investments on the digital side — internet, mobile, we’re getting ready to do some things with the iPad.” But he assured me that nothing would happen right now, not during the recession. The

PennySaver

has always been strongest when the economy is the weakest; the first issue was printed during the Great Depression in someone’s garage. The word was never trademarked, so the

PennySaver

Maryland is unaffiliated with

PennySaver

Florida and

PennySaver

Nevada. They’ve all started online versions of themselves in the last decade, and the print versions of all of them will be discontinued within the next decade.

So this recession was perhaps the last hurrah for the

PennySaver

. The internal slogan of the company in 2009 was “Now Is Our Time.” This seemed like a pretty upbeat approach to the crisis. Just claim it! Own it. Dibs on the recession! The

PennySaver

catered to people for whom ten dollars was worth some trouble — people who saved pennies. Which, right now, was a lot of people.

—

$2.50 EACH

—

—

Now when friends asked me about how my script was going, I responded with the good news about my new job as a reporter for a newspaper that didn’t exist, interviewing people I found through a soon-to-be-extinct piece of junk mail. And because I was refused by the majority of people I called, the ones I met with did not feel random — we chose each other.

Paramount was completely outside my understanding of LA. I just did what the GPS told me to, and then I was there. It was hotter than where I lived; the blinding new pavement barely concealed the desert. I was much too early, so I drove up and down the streets, past rows of identical new houses. I could picture the man who’d built them, a hammer in one hand and the other hand hitting his forehead for the thousandth time as he stepped back from his newest creation and saw that it was, once again, exactly like the last house he’d built, the one next door. I hate it when I keep having the same bad idea, so I could empathize with him. It seemed like a tough neighborhood for a bullfrog that was just getting started, a tadpole. I hurried back to the address, now late. I’m always late and it’s always because I get there too early.

Andrew turned out to be a seventeen-year-old with three ponds in his backyard. Teenage boys never really made sense to me, and I’ve pretty much avoided them since high school. But Andrew was the one kind of teenage boy I was familiar with: the sweet, curious loner. My brother had also built ponds in high school. Andrew’s ponds were thick with water hyacinths and the special fish that eat mosquito eggs. Actual lily pads floated in the sun and the frogs seemed happy, as suburban frogs go.

Miranda: How’d you make this?

Andrew: I just dug.

Miranda: Did you read about ponds, or how did you figure it out?

Andrew: I didn’t really read about it. People just told me. Everything ended up working out little by little.

Miranda: What do you like about it?

Andrew: I don’t know. It’s just relaxing. Watching all this, it relaxes me a lot.