IT Manager's Handbook: Getting Your New Job Done (30 page)

Read IT Manager's Handbook: Getting Your New Job Done Online

Authors: Bill Holtsnider,Brian D. Jaffe

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Information Management, #Computers, #Information Technology, #Enterprise Applications, #General, #Databases, #Networking

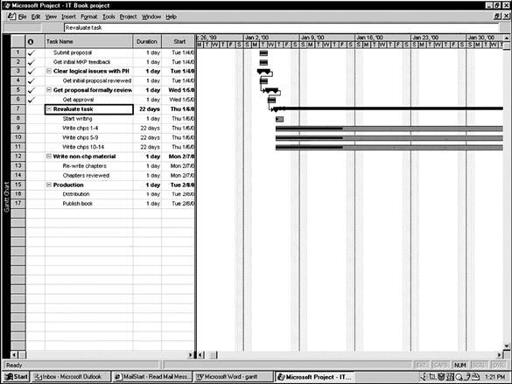

A Gantt chart allows you to quickly see what is supposed to happen and when. It tracks time along the horizontal axis. The vertical axis lists all the tasks associated with the project, their start and end dates, and the resources required.

For an example of a Gantt chart that can be generated from Microsoft Project, see

Figure 4.2

. When you generate the Gantt chart for a particular project, you and every member of the project team (along with anyone else who is interested) can see the true scope of it, the time frames, tasks, dependencies, resource assignments, and such of the entire project. Gantt charts rarely fit on a single page, by the way, so it is common for the entire report to require a whole wall to view when all the printed pages are taped together.

Figure 4.2

Sample Gantt chart.

PERT

Charts and

Critical Paths

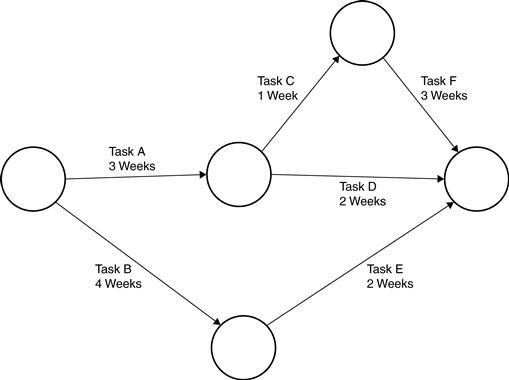

Program Evaluation and Review Technique (PERT) charts or PERT diagrams are graphic representations of the dependencies between tasks in a project.

PERT is basically a method for analyzing the tasks involved in completing a given project, especially the time needed to complete each task, and identifying the minimum time needed to complete the total project.

In

Figure 4.3

, a circle represents a task start or end and a line between two circles represents the actual tasks and how they’re related.

Figure 4.3

PERT chart.

Critical Path

One of the more helpful pieces of information from a PERT chart identifies the

critical path

. The critical path is the series of tasks or events that determine the project’s total duration. In other words, if any of the tasks on the critical path take longer than expected, then the entire project will be delayed by that amount of time. Tasks that aren’t on the critical path won’t have the same influence on the overall project for various reasons (perhaps because they’re done in parallel, as opposed to sequentially).

In

Figure 4.3

, the critical path consists of tasks A, C, and F. If any of these tasks takes longer than expected, it will delay the project as a whole. Activities outside the critical path can change (up to a point) without impacting the entire project. “

Slack time

” is the term used to indicate how much a noncritical path task can be delayed without impacting the project as a whole.

Both Gantt and PERT charts allow you to identify and track your tasks. Creating a milestone in your Gantt chart allows you to add a very useful level of functionality to your project tracking.

A milestone is a major event in the life of a project. A large project can have many milestones: Moving your company’s offices from New York to Raleigh will not only have many individual tasks, but it will also have many milestones. When the decision is officially made, for example (it might have been bandied around for years), is a milestone. But that will be only the first milestone; when the new site is selected, when the lease for the new building is signed, when the phones and wiring are complete, when the data center is ready, when the telecommunication lines are turned up, when office construction is done, when the first people start working in the new building, and so on, are all milestones.

Think specifically about what needs to be accomplished to reach your project goal. Begin by breaking the objective down into a few milestones. You don’t need a lot of detail here, but divide the project into a few chunks so that you can begin thinking about the kinds of people you want on the project team, and maybe begin to develop some perspective on time frames, costs, and other resources.

Updates to Management and the Team

One of the things that everyone wants to know about a project is: “How is it going?” Certainly your boss and the project sponsor want to know this, and the project team needs to be told as well. Oftentimes a project is so big that team members are only familiar with their own piece and aren’t aware of the overall project as a whole.

Regular project meetings (discussed in the section

“Productive Project Meetings”

later in this chapter on

page 128

) can be helpful for keeping members of the team up to date. But these meetings may not be sufficient for everyone; some people are only involved in the project during certain periods, for example, and therefore don’t attend every meeting. Sending out project status reports and posting meeting agendas and minutes, as well as a current version of project plans, are two ways of making sure that everyone has access to data they need.

Summary Updates

Gantt charts, PERT charts, critical paths, and so on are useful tools, but the chances are that your manager, the project sponsors, and the stakeholders may not want to see that level of detail. Even your own team members may not want to wade through all of that just to see if things are on track. Providing regular updates that summarize progress can be valuable to all. These summaries can include the following topics:

•

Accomplishments since the last update

•

Mention of those items in progress and whether they’re going faster or slower than expected

•

Upcoming activities

•

Issues and concerns (perhaps vendor deliveries are taking longer than expected or a key member of the team resigned recently)

•

Overall status: this is the opportunity to identify if things are going as planned or whether you’re anticipating delays, cost overruns, etc.

Determining the appropriate content, who sees it, and how often these updates go out is a matter of judgment. For example, a daily report for a two-year-long project may be overkill. It may make more sense to do it monthly for the first 18 months and then switch to biweekly and weekly as the project gets closer to implementation. Similarly, the summary just given may be sufficient for your boss, but perhaps an even briefer summary is appropriate for her boss.

Red, Yellow, Green Indicators

Another technique used to keep everyone informed about project status is to use red, yellow, and green status indicators for key items. Stealing from the traffic light paradigm, they are a simple and effective way of communicating the status that might otherwise get lost in a verbose explanation. These indicators are usually included as part of other status reports and are associated with key tasks and milestones.

4.6 Phase Five: Close Out the Project

Writing a Closeout Report

A Closeout Report is the report written at the end of a project. It can be a brief, three-page document or a 50-page, detailed report. It should contain, at minimum, the purpose of the project and how well the team executed that purpose. Additional components of a Closeout Report can include a brief history of the project, specific goals accomplished and/or missed, resources used, which aspects went well, and what lessons were learned from things that didn’t go well.

One simple method of generating a Closeout Report is to take the initial Project Charter—the document you worked so hard to create at the beginning of the project—and compare it directly to what you accomplished during the project. Earlier in this chapter we discussed developing a plan with a Closeout Report in mind. For example, say your plan called for the purchase and installation of six new servers in less than two weeks; you accomplished that, so identify the goal, the step, and the accomplishment. Name names, specify how much money and time you saved, give credit where it’s due, and pat your team on the back.

Additional Accomplishments

If relevant, add the new uses or new procedures that your project uncovered. Maybe the new system you installed caught the attention of another department and it’s now serving two purposes. Maybe the automating of the sales process saved more money than expected, as well as reduced errors. Point these successes out.

Dealing with Bad News

If your Closeout Report contains bad news, be clear about it. Compare it to the Project Charter and try to identify how things could have been different. Were the goals set too unrealistically? (“Purchase and install six servers by COB Friday.”) Were you given enough resources? (“You can use one person from Accounting, but that’s it.”) Don’t point fingers at individuals, but try and learn from the problems: What are the lessons the company can learn from this project’s disappointment and failures? (“In the future, changes to the time reporting software will require the involvement of someone from HR.”)

The Need for Follow-Up Activities

It’s pretty rare that a project finishes with every loose end tied up. There are often a number of items that require follow-up. These could be items such as making sure ongoing maintenance is done, the contractors complete all the documentation they promised, and so on.

The completion of projects—the installation of a new billing system, for example—often generates the need for more training. This training can be identified either while the project is being worked on or as it’s completed. If the project completion is going to get a critical function working (such as a billing system), training should be scheduled well in advance to have users ready.

4.7 Decision-Making Techniques

One way to think about the decisions you’ll have to make in your role as a PM is to think about the four types of decision-making mechanisms you can use. These mechanisms are, naturally, only one of many ways to approach the issue. How and why people make decisions is a giant field of research. But these approaches are fairly common methods used to look at the issue.

Four Types of Decision-Making Methods

1.

The Majority Wins.

You take a vote and whichever side of the issue gets the most votes wins. This is certainly the most democratic method, it makes team members feel the most involved, and is often the perfect solution to some clearly defined, black-or-white types of problems. However, it can lead to strange decisions (do you really want the team to meet off-site every week?) and is often not the right method for solving very complex problems. Also, commonly, the

most popular

approach may not be the

best

one. Some people may opt for it because it’s the simplest, quickest, or least expensive.

2.

An appointed subcommittee decides or recommends.

This technique is good because the committee can gather and analyze detailed facts and present a recommendation to the group as a whole. It is bad because not everyone is involved in the decision and because even small committees can get locked up. This approach is excellent for problems that have many components that need to be researched before a decision is made or for issues that need to be decided quickly and outside of the large group. The U.S. Senate, for example, has many committees and subcommittees whose function is to do the often critical preliminary work before presenting an issue to the Senate as a whole.

3.

You decide with help from your team.

This is often the most efficient and most popular method. Many decisions on a project don’t lend themselves to group dynamics; there is either not enough time or the issue isn’t all that important to the group (does everyone really have to weigh in on the font choice for the input screen?), but you can solicit opinions from team members that you know care about the issue, and are knowledgeable, and then decide. It’s not 100 percent democracy, but it’s not 100 percent dictatorship, either.

4.

You make the decision by yourself.

A manager will make plenty of decisions by himself and no one will care. To keep a project moving along, sometimes it’s critical simply to make a decision and move on. (The team lost two programmers on Friday, for example; you decide to contact HR that afternoon to begin to fill those positions. You know other people in the group feel the positions should be filled with analysts, but you don’t, and time is ticking away. Make the decision and go forward.)